Journal of Law, Information and Science

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Law, Information and Science |

|

KHIN THAN WIN[*], PROFESSOR JOAN COOPER[**], PROFESSOR PETER CROLL*, DR. CAROLE ALCOCK *

The increasing use of Information Technology in health care has highlighted the need for privacy especially when accessing electronic health data. As computerised medical records are integrated among health care institutions, data can be accessible from different places by different users and this increases the risk of invasion of privacy. Misuse of patient health data may harm patients and undermine the quality of health care.[1] Computerisation of medical records created some challenges in traditional legislation about use and disclosure of health information. The dilemma of who owns the information and who has access to it needs to be resolved before full implementation of an electronic health record. This paper focuses on possible solutions to some of these issues.

Many healthcare institutions around the world are seeking to develop an electronic health record system because traditional medical records are inadequate in meeting the needs of modern medicine.[2] Every time a patient consults the doctor, a medical record is created. Throughout their lives, patients may have consulted different health care providers and patients’ data may be stored in different institutions. Pathology, Pharmacies and Radiology may also have patients’ data. Longitudinal patient records, patient records that contain data covering a period longer than one disease episode, are needed for effective decision making processes in patient care.[3] To optimize patient care, patients’ data should be accessible by authorised persons from different places. Integration of patients’ medical records from different institutions is needed for successful sharing of information.

Patient confidentiality is an important issue especially with clinical databases and the Internet. Most clinical databases at present are operated within a private network or intranet.[4] Issues of confidentiality and abuse of data cause many health care providers to oppose the coordination of medical databases despite the potential benefits.[5]

Electronic health records assist not only with clinical matters (reporting results of tests, allowing direct entry of orders by clinicians, facilitating access to transcribed reports, and in some cases supporting telemedicine applications or decision-support functions), but also with administrative and financial topics (tracking of patients within the hospital, managing materials and inventory, supporting personnel functions, managing the payroll, and the like), research (for example, analyzing the outcomes associated with treatments and procedures, performing quality assurance, supporting clinical trials, and implementing various treatment protocols), scholarly information (for example, accessing digital libraries, supporting bibliographic searching, and providing access to drug-information databases), and even office automation (providing access to spreadsheets, word processors, and the like). They are electronic, accessible, confidential, secure, acceptable to clinicians and patients, and integrated with other types of non-patient-specific information.[6]

Possible models of electronic health records in Australia are: closed systems controlled by the health care provider (decentralized), open systems (centralized), and patient controlled systems, for example smart cards.[7]

Open systems will allow maximum access to the record by clinicians but maximum threat to confidentiality of patients’ records compared to other systems. Patient controlled systems will allow maximum privacy and control of records by patients. March 2005 is the target for full implementation of first generation person-based electronic health records at primary care level, and level 3 Electronic Patient Records at all acute hospitals within Australia.[8]

Privacy in health is the right and desire of a person to control the disclosure of personal health information.[9]

Confidentiality is a form of informational privacy characterised by a special relationship such as the physician-patient relationship. Personal information obtained in the course of that relationship should not be revealed to others unless the patient is made aware and consents to disclosure.[10]

Security is a collection of policies, procedures, and safeguards that help maintain the integrity and availability of information systems and controls access to their contents.[11]

Since the fourth century B.C. according to the Hippocratic Oath, doctors have needed to maintain the patient’s confidentiality.[12]

Whatever, in connection with my professional practice or not, in connection with it, I see or hear, in the life of men, which ought not to be spoken of abroad, I will not divulge, as reckoning that all such should be kept secret.[13]

If a patient’s information is disclosed accidentally or unintentionally, it may cause embarrassment, infringement of privacy, ruin or damage to the individual’s career, dismissal from employment, loss of job opportunity, damage to or loss of health insurance worthiness, financial loss and disruption of privacy.[14]

Many health care consumers are afraid that their diagnosis and treatment information will be misused[15]

and are concerned that their health information may be used to discriminate against them in employment, insurance or housing decisions and make them the focus of unwanted attention.[16]

Physicians, nurses, nursing assistants, therapist and allied health professionals are primary users of health data. Researchers, educators, third party payers, business administrators, legal representatives, auditors, employers, public health officials, quality assurance and utilization review staff are the secondary users. As there are many possible users of the electronic health record, confidentiality and privacy are crucial. Carter expressed the view that there should be a code of ethics for those who may handle medical records, for example receptionists, clerks, administrators and laboratory technicians, as they do not have ethical or other requirements to protect consumer confidentiality unless that is included in their contract.[17]

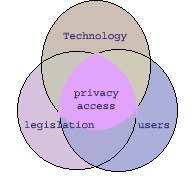

Figure 2. Venn diagram User, Technology, Legislation

Users, technology and legislation are interrelated with the privacy and reliability of health data. Users should abide by the law of privacy and legislation should be implemented according to the changing technology. Advancement of technology increases user accessibility and privacy protection involving the use of technology. Health care providers’ reluctance to share information in local area networks can be overcome by providing adequate technology to support security measures and privacy legislation to protect health data.[18]

The American Academy of Pediatrics has pointed out that protection of patient records can be achieved by implementing security policies to control access, providing appropriate authorisation before releasing the health data and providing additional security measures to more sensitive data.[19]

The issue of ownership of medical records is pivotal to the determination of privacy and access to patient information.[20] Many hospitals consider they own the data in the medical record systems and patients consider that their medical information is their own.[21] Health records consist of objective factual material and the subjective opinions of the treating doctors.[22] Therefore the doctors’ copyright interest should be respected, and the question is: should that override the patient’s right to access his or her health information? This question is debatable and there is difference of opinions as to who owns the record; even the legal opinion is divided. The European Union’s data protection directive legislation enables patients to have access to their medical records. The European Union initiatives were aimed at ensuring all European citizens having the health smart card to enable secure and confidential access to information by 2003.[23] The Supreme Court of Canada (1992) maintained that the right of access to information in the medical record was a personal right of the patient, although the file remained the property of the hospital.[24] The dilemma of who owns the information should be resolved before the electronic health record system is to be implemented.

Consent in medicine, in both the context of therapy and research has been debated since the Second World War.[25] The Nuremberg trial was the typical example of medical research done on human beings without having any informed consent. The Nuremberg code of 1947 has highlighted the ethical regulations in human experimentation based on informed consent.[26] The use of informed consent before this was mainly for therapeutic and physical application in treatment and research.

Consent for health information means a patient is informed and provides voluntary agreement to confide or permit access or collection.[27]

Under the Commonwealth Privacy Act the definition of consent includes express or implied consent.[28]

Express consent (Explicit consent) is a consent given explicitly, either orally or in writing. Express consent is unequivocal and does not allow any exercise of influence on the part of the provider seeking consent.[29]

Implied consent arises where agreement may reasonably be inferred from the action or inaction of the individual and there is good reason to believe that the patient has knowledge relevant to this agreement.

Many organizations with access to health information have not obtained the individual’s consent for disclosing personal information.[30] Effective notification and truly informed consent requires that individuals know and understand the contents of the record and what it is to be used for. It is unethical claim the implied consent when the patient is not fully aware of the information disclosure.

Disclosure is the revealing of identifiable health information to anyone other than the subject.[31]

The Data Protection Act, 1998, United Kingdom includes sensitive data and states that health data cannot be processed in the absence of explicit consent unless needed for medical purposes or by a professional who in a particular circumstance owes a duty of confidentiality.[32]

There is increasing emphasis on patient autonomy and patient’s rights. Patients need to know how the information will be kept, who can access their records and for what purpose.[33] Patients’ medical data can be revealed only with the patients’ consent except in emergencies or when the law obliges the healthcare provider.[34]

In certain serious medical situations, the doctrine of implied consent allows it to be assumed that a patient would provide consent if the patient were competent, even though the patient is incapable of communicating consent, unless the patient has stated refusals to allow emergency release.[35]

There is a need to balance the public interest in medical research against the public interest in privacy.[36]

Medical research should be carried out in such a way as to minimize the intrusion on people’s privacy, consent must be obtained or de-identified information should be used.

The British Medical Association has stated that the use of information for research is currently accepted as long as it is carried out within the guidelines and subject to monitoring by appropriately constituted research ethics committees. But patients should know that it might involve the use of their records.[37]

Researchers worry that requirements for patient’s consent and anonymisation will undermine vital medical research.[38] Production of substandard flawed research is less ethical than the use of anonymised data by professional researchers.[39] Medical research, which involves monitoring of vaccines safety, outbreak responses, and control of infectious diseases, can be undermined if the patient’s privacy overrides the need for surveillance.[40]

There are conflicting views of privacy and access of electronic health records. Rind et al. have pointed out that it is not possible to achieve both perfect confidentiality and perfect access to patient information, whether that information is computerised or hand written.[41] In the United States the Federal Register, final rules by the Department of Health and Human Services give health care providers full discretion in deciding how much information to include when sending a patient’s records to another provider for treatment.[42]

To protect the patient’s privacy, each patient’s electronic record must be access controlled.[43] Each clinical record must be marked with a list of names to whom information may be made accessible. The access should be allowed on a need to know basis and it is essential to consider how this should be determined.[44] The Australian Medical Association’s 1997 guidelines for doctors allowing patient access to medical records, provide that patients have a right to be informed of all factual information contained in the medical record relating to their care but do not have the absolute right to access medical records.[45] National Privacy Principle 6 also recommends that the organization should provide individuals with access personal information and health information except in cases where providing such access would pose a serious threat to the life of an individual.[46]

There are discussions about the right of access by the parents to their children’s health records and parents should not have an automatic right of access to their children’s records. A child or a young person may choose not to disclose certain information contained in an electronic health record and make it inaccessible to other people, including his or her parents. NSW Ministerial Advisory Committee believes that children and young people should have the right to choose which information will be available on the linked electronic health record.[47]

A doctor’s duty to act in the best way to guard the public interest and respect patient’s rights of confidentiality is a complex issue. In New Zealand in 1983, a general practitioner was charged in court because he had disclosed a patient’s heart condition, which can be dangerous for driving a children’s school bus, and the patient sued him in court.[48] It is advisable that the need to disclose sensitive information to the governing authority should be discussed with the patient and the patient’s permission should be sought first. This case could be decided differently in different countries.

Conflicting views concerning accessibility of information about sexually transmitted disease and HIV status of patients in provider and government’s networking has hindered introduction of IT into the NHS in United Kingdom by several years.[49]

Demands of increasing levels of access to health data from insurers and employers raise new issues in security of personal health data.[50] Final rules by the Department of Health and Human Services prohibits companies that sponsor health plans from accessing or using personal health information for any employment related purposes without an authorization from the patient/employee.[51] In South Africa, the Health Professional Council faces high court action under accusations of misadministration because the council has failed to take actions against doctors who disclosed HIV positive patient data to employers and those employee/patients were fired.[52] Health data should not be used to discriminate against the employee and legislation is needed to enforce this.

Patient authorisation is required for using health data for marketing purposes.[53] Patients’ confidentiality should not be compromised by selling or providing patients’ records.[54] Iceland has sold the medical and genealogical records of its 275,000 citizens to a private medical research company.[55]

Is it ethical for the government to sell the citizens’ medical data for research purposes? Can anyone be sure that the data will be used only for the beneficial effects for human beings? Can the government interest override the public interest? It is justifiable for the Iceland government as the Iceland Parliament adopted the act on health sector database in 1998 December stating data entered in the health sector databases are the property of the Icelandic Nation.[56]

In Australia, The Health Communication Network (HCN), a privately owned e-health company has planned to sell the information gathered by its software.[57]

Although HCN has stated the patients records will be de-identified, it cannot be guaranteed that they will not be identifiable.[58] This news has alarmed the privacy concerns to the public. It is a misuse of data by a third party because HCN software has gathered the data without the full knowledge of the GPs using their software. This incident points out that health care providers need to have knowledge of technology so that unethical use of data can be prevented.

Proper disposal of health records should be carried out. Retention periods of records vary according to the type of documentation.[59] Patients’ privacy can be undermined because of improper disposal of patients’ records. For example, 2000 patients’ records from Smitty’s supermarket pharmacy in Tempe, Arizona were found in an auctioned old computer and this is a breach of patients’ confidentiality.[60] In Messina, a patient was surprised to know that his records from treatment in Naples Community Hospital in 1994 were seen at the public recycling center. There were reams of documents in six large recycling bins.[61]

As patients’ records contain sensitive data, health data clearing houses need to provide appropriate measures to maintain the confidentiality of patients’ records.[62]

The National Electronic Health Record Task Force of Australia has stated that any breach of confidentiality by a general practitioner may lead to disciplinary offences, civil penalties and criminal penalties.[63] In the United States the Final Rule that became effective on February 2001 as provided by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 stated that: violation of standards of final rules are subject to Civil penalties of $100 per violation, up to $25,000 per person, per year for each standard; criminal penalties for entities of up to $50,000 and one year in prison for improperly disclosing or obtaining health information or up to $100,000 and five years in prison for obtaining health information under false pretenses and up to $250,000 and ten years in prison for obtaining or disclosing protected health information with the intent to sell, transfer for use for personal gain, commercial advantage or malicious harm.[64]

Principles of privacy protection apply equally to paper and electronic records.[65] Paper based records can be stolen by an insider or outsider who is interested in the records for certain purposes. Electronic health record systems can be infiltrated by hackers. For example, a hacker infiltrated the University of Washington Medical Center’s computer system and stole at least 5000 cardiology and rehabilitation medicine patients’ records.[66]

Kane, a Dutch Hacker had pointed out the vulnerabilities of the system because he had penetrated an unidentified medical centre in New York and another in Holland.[67]

Persons responsible for electronic health record systems need to be aware of privacy risks and implement proper measures to deter unauthorized access. Medical records can be the target of unscrupulous attackers, whether they are paper based or computerised. Linked medical records systems with unique identifiers can be more easily accessed for quality care and it can also be argued that they are more vulnerable to a security breach because that will lead to increased accessibility to the unauthorized person as well. Passwords and other technologies such as encryption, public key infrastructure, firewall and network service management, software management, rights management tools and system vulnerabilities management tools provide much more security where electronic records are concerned.[68] Electronic data files are disseminated more easily than paper records and therefore they may be subjected to more unintended use.[69] Use of unique identifiers may enhance the accessibility of records and may have higher risks of threats to privacy.[70]

Security for web based electronic medical records is a lot better than most physicians believe.[71]

Threats to the confidentiality of medical records can be from insiders by innocent mistakes such as accidental disclosure, or by abuse of their record access privileges.[72] The University of Michigan Medical Center patients’ records were left exposed to the public on the Internet because they thought that they were on a special server protected with a special password.[73] It was an innocent mistake but the patients' confidentiality was breached. The case of the Florida state public health worker who sent the names of 4000 HIV positive patients to two Florida newspapers was a case of abuse of access privilege for the purpose of profit. To deter this kind of breach, there should be harsh legislation with strong penalties. Authorised providers who are insiders are the most common threats to patients’ confidentiality by the inappropriate accessing of information.

Cases of computer security breach known to the public may just be the tip of the iceberg, as any institution attacked may not want to reveal that to the public for fear of loss of reputation and trust worthiness.

Barrow and Clayton have stated that the goals of the information security in health care should not be set by technology but policy and can define what is to be protected to which degree and who has the privilege to access protected items.[74] Privacy legislation is needed to ensure the integrity of data and to protect against unauthorised uses and disclosures.[75]

In the United States, Federal Register, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) and National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics have strongly emphasized the importance of health privacy.[76]

The National Research Council has discussed in detail the limitations of Federal and State protection, technical approaches and organizational approaches for protection of privacy in medical records.[77]

To ensure that technology assists society without compromising the trust of the public and private sectors appropriate privacy legislation is needed. The Commonwealth Privacy Amendment (Private Sector) Bill 2000, an extension of the National Privacy Principles[78]

contained in the Privacy Act 1988[79]

has been introduced in Australia and it has special provisions for the protection of health information. The Private Sector Bill provides baseline regulation for all health information and codes to be developed.[80]

The Australian Medical Association (AMA) is concerned that the proposed legislation is burdensome to medical practitioners without enhancing the current legislative mechanism for the protection of patient privacy and therefore will not be welcomed by the medical professionals. The AMA felt that the regime failed to respect and recognize practitioners’ rights to privacy in their professional needs.[81]

The legislation and amendments concerning health information should be explained to the professions and public sector groups with a properly funded educational program.[82]

Providing a knowledge and understanding of the legislation and amendments will answer any concerns about privacy and access to electronic health records. By having an effective educational program professions and the public will understand the value of their responsibilities relating to privacy.

The NSW Ministerial Committee on privacy and health information has expressed concerned regarding the privacy of health information after the implementation of electronic health record systems. The current legal framework for health information in NSW includes, privacy legislation which applies to public sector agencies, health related legislation with specific provisions on confidentiality, proposed federal privacy legislation for the private sector in Australia and common law medical confidentiality obligations applying to practitioner-patient relationship.[83]

Privacy legislation implementation needs to be balanced according to the health care reforms and all sectors involved need to participate in this implementation.

The emergence of the electronic health record system changes the information management paradigm. Advancement of information technology assists the simultaneous access to records by doctors but at the same time because of easy accessibility, threats to privacy become inevitable. The challenge faced with the advanced technology is to maintain privacy. Before electronic health records, consent taken from the patient was mainly focused on permission for medical procedures which entailed the paper based records located only in the GP’s office or in the health care institution. The easy accessibility of complete, accurate health data in electronic health record causes concern over the patient’s privacy and this highlights the importance of gaining consent for the use of health information.

Invasion of privacy becomes the major concern, as there is increased accessibility of health care data in electronic health records. Maintaining the patient’s confidentiality in situations when the patient chooses not to disclose a certain part of the information becomes a dilemma. Should confidentiality be maintained even if it is harmful to the community? Could that be overridden because of the public interest? Could that be ignored if it is in a life-threatening situation? Would there be any impact on effective health care and treatment because certain parts of the record are not available according to the patient’s consent? Would that undermine medical research because of inaccurate data? A lot of issues are raised for what is clearly a multi-layered, multi-access control system. One cannot assume that technology in particular current database systems would be compatible with the demands of legislation designed for a multi-access system with appropriate security.

There is a need for flexibility and health care providers should be able to access data for medical purposes and research. Use of health data for research is justifiable for researchers as the outcome can be beneficial to the society. Scientific evidence documented in thorough medical research can give new knowledge to health care so policy and legislation should determine the best possible solution for using the health information in the medical records. Therefore, the legislations provided should be acceptable not only to the patients but also to the health care providers.

The technology should comply with legal needs to survive and legislation should also comply with the public interest. Therefore equilibrium is needed to ensure a balance between the health care providers' interests and patients' (public) interests. Efficient legislation can help to deter unauthorised access and improper conduct but it should not undermine effective health care. It should assist in providing comprehensive, reliable and efficient health care. Privacy, confidentiality and access must be balanced and legislation should complement the needs of the state or government and public concern.

A Health Information Network for Australia, Report to Health Ministers by the National Electronic Health Records Taskforce, Commonwealth of Australia, http://www.health.gov.au/healthonline/ehr_rep.pdf, accessed October 2000.

American Academy of Pediatrics: Pediatric Practice Action Group and Task Force on Medical Informatics(1999), 'Privacy protection of health information: Patient rights and pediatrician responsibilities', vol. 104 pp 973-977.

Anderson R (2001), 'Undermining data privacy in health information', The British Medical Journal, vol: 322, pp 442-443.

Amatayakul M. (1998), 'The state of the computer based patient record', Journal of American Health Information Management Association, October, http://www.ahima.org/journal/features/feature9810.1.html, accessed February 2001.

Australian Medical Association comments on proposed Privacy Amendment (Private Sector) Bill (2000), Australian Medical Association, http://www.domino.ama.com.au/dir0103/, accessed 24 May 2001.

Barrows R.C. Jr, Clayton P.D. (1996), 'Privacy, confidentiality, and electronic medical records', Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, vol: 3, pp 139-148

BMA ethics (2001), http://web.bma.org.uk/public/ethics.nsf/webguidelinesvw?openview, accessed May 2001

Buckovich S.A., Rippen H.E., Rozen MJ(1999), 'Driving toward Guiding Principles: A goal for privacy, confidentiality and security of health information', Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, vol:6, pp 122-133

Carter M. (1998), 'Should patients have access to their medical records?' The Medical Journal of Australia, vol: 169, pp 596-597

Carter M. (2000) 'Integrated electronic health records and patient privacy: possible benefits but real dangers', The Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 172, pp 28-30

Chin T. (2001), 'Security breach: Hacker gets medical records', American Medical News, vol:44, pp 18-19

Chyna J.T. (2000), 'Electronic medical records', Health Care Executive, vol. 15, pp 14-18

'Confidentiality of Medical Records (1998): A situation analysis and AHIMA’s position', American Health Information Management Association, www.ahima.org/infocenter/current/white.paper.html, accessed February 2001

Cox P. (2001), 'Using patient identifiable data without consent', The British Medical Journal, vol. 322, pp 858

Crompton M. (2000), 'Enhancing privacy and confidentiality in the world of e-health', Proceedings from the National Health Online Summit, Adelaide, August 2000, pp 35-37, http://www.health.gov.au/healthonline/summit/summit.pdf, accessed 25 May 2001

Crompton M. (1999), Privacy Commissioner's report on the application of the national principles for the fair handling of personal information to personal health information, Office of the Federal Privacy Commissioner

Dalander G., Willner S., Brasch S. (1997), 'Turning a dream into reality: The evolution of a seamless electronic health record', Journal of American Health Information Management Association www.ahima.org/journal/features/feature.9710.2.html, accessed October 2000

Dalla-Vorgia P., Lascaratos J., Skiadas P. and Garanis-Papadatos (2001), 'Is consent in medicine a concept only of modern times?', Journal of Medical Ethics, vol:27, pp 59-61

Data Protection Act 1998, http://www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1998/19980029.htm, accessed 23 May 2001

Dearne K. (2001), 'Prescribing a privacy cure', Australian IT, May 1, pp 44.

Denley I., Smith S.W. (1999), 'Privacy in clinical information systems in secondary care', The British Medical Journal, vol. 318, pp 1328-1331.

'Draft health privacy guidelines' (2001), The consultation document issued by the office of the federal privacy commissioner, Sydney, NSW http://www.privacy.gov.au/rfc/index.html, accessed 21 May 2001.

Evans B., Ramay C.N. (2001), 'Integrity of communicable disease surveillance is important patient care', The British Medical Journal, vol. 322, pp 858.

Eysenbach G. (2000), 'Consumer health informatics', The British Medical Journal, vol. 320, pp 1713- 1716.

Federal Register (2000), 'Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information, final rule', Department of Health and Human Services, vol. 65, no. 250 http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/hipaa, accessed April 2001.

Fraser H.S.F., Kohane I.S., Long W.J. (1997), 'Using the technology of the world wide web to manage clinical information', vol. 314 pp 1600.

Garfinkel S. (2000), 'Computerized patient records: the threat', Database Nation, The death of privacy in the 21st century, pp 149-151

Gerber P. (1999), 'Medicine and the law: Confidentiality and the courts', The Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 170 pp 222-224.

Goldberg I.V. (2000), 'Electronic medical records and patient privacy', The Health Care Manager, March, pp 63-69.

Gostin L.O., Turek-Brezina J., Powers M., Kozloff R., Faden R., Steinauer D.D. (1993), 'Privacy and Security of Personal Information in a New Health Care System', Journal of American Medical Association, vol. 270, no. 20, pp 2487-2493).

Griew A., Briscoe E., Gold G., Groves-Phillips S. (1999), 'Need to know; allowed to know: The health care professional and electronic confidentiality', Information Technology and People, vol. 12, no.3, pp 276-286.

Guidelines under section 95 of Privacy Act 1988 (March 2000), Common wealth of Australia, http://www.health.gov.au/nhmrc/publicat/pdf/e26.pdf, accessed April 2001.

Hartsfield S. (2001), 'HIPAA update: Federal protections for health information', Health Management Technology, vol. 22, pp 12.

HHS Fact Sheet (2000), 'Protecting the privacy of patient’s health information: summary of the final regulation', U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, http://www.os.dhhs.gov/news/press/2000press/00fsprivacy.html, accessed May 2001.

Hornblum A.M (1997), 'They were cheap and available: prisoners as research subjects in twentieth century America', The British Medical Journal, vol. 315, pp 1437-1441.

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs (2000), Patient access to medical records, Advisory Report on the Privacy Amendment (Private Sector) Bill 2000, The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, June pp 75-85.

Johannesburg P.S. (2001), 'Medical council fails to act over breaches of confidentiality', The British Medical Journal, vol. 322 pp. 386.

Knoppers B.M. (2000), 'Confidentiality of Health Information: International Comparative Approaches', A Health Information Network for Australia.

Lemos R. (2000), 'Medical privacy gets CPR', December. http://www.zdnet.com/zdnn/stories/news/0,4586,2667243,00.html, accessed 17 May 2001.

Mandl K.D., Szolovits P., Kohane I.S. (2001), 'Public standards and patients’ control: how to keep electronic medical records accessible but private', vol. 322, pp 283-287.

Markoff J. (1997), 'Patients file turn up in used computer', The New York Times, April 4 .

Medical Record Privacy (1999), Electronic Privacy Information Center, http://www.epic.org/privacy/medical, accessed 17 May 2001.

'Medical records up for sale' (2001), Australian IT, www.news.com.au/common/story-page/0,4057,1770714/255E2,00.html, accessed 17 May 2001.

Murray D (2001), 'Health privacy botched', Information Week, April, pp14-18.

National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (2000), Report to the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services on Uniform data standards for patient medical record information http://ncvhs.hhs.gov/hipaa000706.pdf, accessed November 2000.

National Privacy Principles (2000), Attorney General’s Department, Commonwealth of Australia, http://law.gov.au/privacy/royalnpp.pdf, accessed 21 May 2001.

National Research Council (1997), For The Record, Washington, D.C, National Academy Press.

NSW Ministerial Advisory Committee on Privacy and Health Information (2000), A discussion of the Issues, November, http://www.lawlink.nsw.gov.au/pc.nsf/pages/elechealth8, accessed 21 May 2001.

NSW Minister Advisory Committee on Privacy and Health Information (2000), Panacea or Placebo? Linked Electronic Health Records and Improvement in Health Outcomes, December.

Privacy Legislation, Australian Medical Association, http://www.domino.ama.com.au/dir0103/4236d42a780b68d94a2568850042e3de.html, accessed 24 May 2001.

'Putting patients first (1999), Comments on Bill C-6', submitted to the senate standing committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology http://www.cma.ca/advocacy/political/1999/11-29/index.html, accessed 23 May 2001.

Reykjavik (2000), 'Iceland sells its medical records, pitting privacy against greater good', CNN news, http://www.cnn.com/2000/WORLD/europe/03/03/iceland.genes, accessed 17 May 2001.

Rind D.M., Kohane I.S., Szolovits P., Safran C., Chueh H., Barnett O. (1997), 'Maintaining the confidentiality of medical records shared over the internet and the world wide web', Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 127, pp 138-141.

Rindfleisch T.C. (1997), 'Confidentiality, Information Technology and Health Care', Communications of the Association of Computing Machinery, vol. 40, pp 93-100.

Roberts L. (2001), 'Argument for consent may invalidate research and stigmatize some patients', The British Medical Journal, vol. 322, pp 858.

Schoenberg R., Safran C. (2000), 'Internet based repository of medical records that retains patient confidentiality', British Medical Journal, vol. 321, pp 1199-1203.

Seidelman W.E. (1996), 'Nuremberg lamentation for the forgotten victims of medical science', The British Medical Journal, vol. 313, pp 1463 - 1467.

Shortliffe H.E., Blois (2000), 'The Computer Meets Medicine and Biology: Emergence of a Discipline', Medical Informatics: Computer Applications in Healthcare and Biomedicine: Chapter 1, Springer Verlag.

Songini M.C., Dash J. (2000), 'Hospital confirms hacker stole 5,000 patient files: attack points to need for standards for patient records', Computer World, vol. 34, iss 51, pp 7.

'Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information: A brief summary of the final rule' (2001), Coalition for Health Information Policy, www.amaia.org/resource/policy/chip/final_rule_summary.html, accessed March 2001.

The Hippocratic Oath, http://members.tripod.com/nktiuro/hippocra.htm, accessed March 2001.

Unique Health Identifiers for individuals: A White Paper (1997), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, http://www.epic.org/privacy/medical/hhs-id-/98.htm, accessed May 15, 2001.

Van-Bemmel J.H., Musen M.A. (1997), 'Hospital Information systems: Clinical use', Handbook of Medical Informatics, Springer-Verlag, Germany, pp 341.

Waegemann C.P. (2000), 'A Matter of Privacy for ehealth: Security Policies - International Privacy - Internet Security' http://www.medrecinst.com/conferences/asia/proceedings/10-00/privacy.pdf, accessed May 2001.

Waegemann C.P. (2000), 'The Personal (Consumer) Health Records', Proceedings of e-Health Asia October 2000, http://www.medrecinst.com/conferences/asia/proceedings/10-00/phrecod.pdf, accessed May 2001.

Zollo C. (2000), 'Public disposal of medical records spur privacy concerns', Naples Daily News, April 23, www.naplesnews.com/00/04/macro/d432996a.htm, accessed 17 May 2001.

[*] School of Information Technology and Computer Science University of Wollongong, NSW 2522 , Australia

[**] Faculty of Informatics, University of Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia

[1] Buckovich, S.A., Rippen, H.E. and Rozen, M.J., ‘Driving toward Guiding Principles: A goal for privacy, confidentiality and security of health information’, Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, vol. 6, 1999, pp 122-133; Goldberg, I.V., ‘Electronic medical records and patient privacy’, The Health Care Manager, March, 2000, pp 63-69.

[2] Shortliffe H.E. and Blois, ‘The Computer Meets Medicine and Biology: Emergence of a Discipline’. In Medical Informatics: Computer Applications in Healthcare and Biomedicine, Springer Verlag, 2000.

[3] Van-Bemmel, J.H. and Musen, M.A., ‘Hospital Information systems: Clinical use’. In Handbook of Medical Informatics, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 1997, p 341.

[4] Fraser, H.S.F., Kohane, I.S. and Long, W.J., ‘Using the technology of the world wide web to manage clinical information’, British Medical Journal, vol. 314, 1997, p 1600.

[5] Goldberg, supra n.1.

[6] Shortliffe and Blois, supra n.2.

[7] A Health Information Network for Australia, Report to Health Ministers by the National Electronic Health Records Taskforce, Commonwealth of Australia, http://www.health.gov.au/healthonline/ehr rep.pdf, accessed October 2000.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Rindfleisch, T.C., ‘Confidentiality, Information Technology and Health Care’, Communications of the Association of Computing Machinery, vol. 40, 1997, pp 93-100.

[10] Gostin, L.O., Turek-Brezina, J., Powers, M., Kozloff, R., Faden, R. and Steinauer, D.D., ‘Privacy and Security of Personal Information in a New Health Care System’, Journal of American Medical Association, vol. 270, no. 20, 1993, pp 2487-2493.

[11] Rindfleisch, supra n.9.

[12] Confidentiality of Medical Records: A situation analysis and AHIMA’s position, American Health Information Management Association, 1998, www.ahima.org/infocenter/current/white.paper.html, accessed February 2001; Medical Record Privacy, Electronic Privacy Information Center, 1999, http://www.epic.org/privacy/medical, accessed 17 May, 2001.

[13] The Hippocratic Oath,

http://members.tripod.com/nktiuro/hippocra.htm, accessed March 2001.

[14] Waegemann C.P. (2000), 'A Matter of Privacy for ehealth: Security Policies - International Privacy - Internet Security'

http://www.medrecinst.com/conferences/asia/proceedings/10-00/privacy.pdf, accessed May 2001.

[15] Dalander, G., Willner, S. and Brasch, S., ‘Turning a dream into reality: The evolution of a seamless electronic health record’, Journal of American Health Information Management Association, 1997, www.ahima.org/journal/features/feature.9710.2.html, accessed October 2000.

[16] A Health Information Network for Australia, supra n.7.

[17] Carter, M., ‘Should patients have access to their medical records?’, The Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 169, 1998, pp 596-597.

[18] Amatayakul, M., ‘The state of the computer based patient record’, Journal of American Health Information Management Association, October 1998, http://www.ahima.org/journal/features/feature9810.1.html, accessed February 2001.

[19] American Academy of Pediatrics: Pediatric Practice Action Group and Task Force on Medical Informatics, ‘Privacy protection of health information: Patient rights and pediatrician responsibilities’, vol. 104, 1999, pp 973-977.

[20] Mandl, K.D., Szolovits, P. and Kohane, I.S., ‘Public standards and patients’ control: how to keep electronic medical records accessible but private’, British Medical Journal, vol. 322, 2001, pp 283-287.

[21] Schoenberg, R. and Safran, C., ‘Internet based repository of medical records that retains patient confidentiality’, British Medical Journal, vol. 321, 2000, pp 1199-1203; American Academy of Pediatrics, supra n.19.

[22] House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, Patient access to medical records: Advisory Report on the Privacy Amendment (Private Sector) Bill 2000, Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, June 2000.

[23] Eysenbach, G., ‘Consumer health informatics’, The British Medical Journal, vol. 320, 2000, pp 1713-1716.

[24] Knoppers, B.M., ‘Confidentiality of Health Information: International Comparative Approaches’, A Health Information Network for Australia, supra n.7.

[25] Hornblum, A.M., ‘They were cheap and available: prisoners as research subjects in twentieth century America’, The British Medical Journal, vol. 315, 1997, pp 1437-1441.

[26] Seidelman, W.E., ‘Nuremberg lamentation for the forgotten victims of medical science’, The British Medical Journal, vol. 313, 1996, pp 1463-1467.

[27] ‘Putting patients first, Comments on Bill C-6’, submitted to the Senate Standing Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology, 1999,

http://www.cma.ca/advocacy/political/1999/11-29/index.html, accessed 23 May, 2001.

[28] ‘Draft Health Privacy Guidelines’, Consultation document issued by the Office of the Federal Privacy Commissioner, Sydney, New South Wales, 2001, http://www.privacy.gov.au/rfc.index.html, accessed 21 May, 2001.

[29] ‘Putting patients first’, supra n.27; ‘Draft Health Privacy Guidelines’, supra n.28.

[30] Goldberg, ‘Electronic medical records and patient privacy’.

[31] BMA Ethics, 2001,

http://web.bma.org.uk/public/ethics.nsf/webguidelinesvw?openview, accessed May 2001.

[32] Data Protection Act 1998,

http://www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1998/19980029.htm, accessed 23 May, 2001.

[33] Fraser, H.S.F., Kohane, I.S., Long, W.J., 'Using the Technology of the World Wide Web to Manager Clinical Information, British Medical Journal, no.7094, vol.314 (1997) pp.1600-1604.

[34] ‘Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information: A brief summary of the final rule’, Coalition for Health Information Policy, 2001, www.amaia.org/resource/policy/chip/finalrulesummary.html, accessed March 2001.

[35] Rind, D.M., Kohane, I.S., Szolovits, P., Safran, C., Chueh, H. and Barnett, O., ‘Maintaining the confidentiality of medical records shared over the internet and the world wide web’, Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 127, 1997, pp 138-141.

[36] Guidelines under section 95 of Privacy Act 1998 (March 2000), Commonwealth of Australia,

http://www.health.gov.au/nhmrc/pulicat.pdf/e26.pdf, accessed April 2001.

[37] BMA Ethics, 2001.

[38] Evans, B. and Ramay, C.N., ‘Integrity of communicable disease surveillance is important patient care’, The British Medical Journal, vol. 322, 2001, p 858; Roberts, L., ‘Argument for consent may invalidate research and stigmatize some patients’, The British Medical Journal, vol. 322, 2001, p 858; Cox, P., ‘Using patient identifiable data without consent’, The British Medical Journal, vol. 322, 2001, p 858.

[39] Roberts, ‘Argument for consent’, supra n.38.

[40] Evans and Ramay, ‘Integrity of communicable disease surveillance’, supra n.38.

[41] Rind et al, supra n.35.

[42] Federal Register, ‘Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information, final rule’, Department of Health and Human Services, vol. 65, no. 250, 2000, http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/hipaa, accessed April 2001; ‘Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information: A brief summary of the final rule’, supra n.34.

[43] Denley, I. and Smith, S.W., ‘Privacy in clinical information systems in secondary care’, The British Medical Journal, vol. 318, 1999, pp 1328-1331.

[44] Griew, A., Briscoe, E., Gold, G. and Groves-Phillips, S., ‘Need to know; allowed to know: The health care professional and electronic confidentiality’, Information Technology and People, vol. 12, no. 3, 1999, pp 276-286.

[45] House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, supra n.22.

[46] Ibid.; Crompton, M., Privacy Commissioner’s report on the application of the national principles for the fair handling of personal information to personal health information, Office of the Federal Privacy Commissioner.

[47] NSW Minister Advisory Committee on Privacy and Health Information (2000), 'Panacea or Placebo?' Linked Electronic Health Records and Improvement in Health Outcomes', December 2000.

[48] Gerber, P., 'Medicine and the law: Confidentiality and the courts’, The Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 170, 1999, pp 222-224.

[49] Anderson, R., ‘Undermining data privacy in health information’, The British Medical Journal, vol. 322, 2001, pp 442-443.

[50] Supra, no.47.

[51] Federal Register, ‘Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information’ supra n.42; ‘Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information: A brief summary of the final rule’, supra n.34.

[52] Johannesburg, P.S., ‘Medical council fails to act over breaches of confidentiality’, The British Medical Journal, vol. 322, 2001, p 386.

[53] ‘Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information: A brief summary of the final rule’, supra n.34.

[54] Dearne, K., ‘Prescribing a privacy cure’, Australian IT, May 1, 2001, p 44.

[55] ‘Iceland sells its medical records, pitting privacy against greater good’, CNN News,

http://www.cnn.com/2000/WORLD/europe/03/03/iceland.genes, accessed 17 May, 2001.

[56] Knoppers, supra n.24.

[57] Murray , D., ‘Health privacy botched’, Information Week, April, 2001, pp 14-18; ‘Medical records up for sale’, Australian IT, 2001,

www.news.com.au/common/story-page/O,4057,1770714/255E2,00.html, accessed 17 May, 2001.

[58] Murray, supra n.57.

[59] Federal Register (1999), 'Retention of Health Information-updated', Journal of AHIMA, vol.70-6,

http://www.ahima.org/journal/pb/99.ob.html.

[60] Markoff, J., ‘Patients file turn up in used computer’, The New York Times, April 4, 1997.

[61] Zollo, C., ‘Public disposal of medical records spur privacy concerns’, Naples Daily News, April 23, 2000, www.naplesnews.com/00/04/macro/d432996a.htm, accessed 17 May, 2001.

[62] Hartsfield, S., ‘HIPAA update: Federal protections for health information’, Health Management Technology, vol. 22, 2001, p 12.

[63] Knoppers, supra n.24.

[64] ‘Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information: A brief summary of the final rule’, supra n.34.

[65] American Academy of Pediatrics, supra n.19.

[66] Lemos, R., ‘Medical privacy gets CPR’, December 2000,

http://www.zdnet.com/zdnn/stories/news/0,4586,2667243,00.html, accessed 17 May, 2001; Songini, M.C. and Dash, J., ‘Hospital confirms hacker stole 5,000 patient files: attack points to need for standards for patient records’, Computer World, vol. 34, iss. 51, 2000, p 7; Chin, T., ‘Security breach: Hacker gets medical records’, American Medical News, vol. 44, 2001, pp 18-19.

[67] Songini and Dash, supra n.66; Chin, supra n.66.

[68] Rindfleisch, supra n.9.

[69] American Academy of Pediatrics, supra n.19.

[70] Unique Health Identifiers for Individuals: A White Paper, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1997, http://www.epic.org/privacy/medical/hhs-id-/98.htm, accessed May 15, 2001.

[71] Grandinettic, D. 'The good news and bad about Web-based EMRs', Medical Economics, Oradell; vol.77, iss. 17, 2000, pp.73-79.

[72] Garfinkel, S., ‘Computerized patient records: the threat’. In Database Nation: The death of privacy in the 21st century, 2000, pp 149-151.

[73] Carter, M., ‘Integrated electronic health records and patient privacy: possible benefits but real dangers’, The Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 172, 2000, pp 28-30.

[74] Barrows, R.C. Jr. and Clayton, P.D., ‘Privacy, confidentiality, and electronic medical records’, Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, vol. 3, 1996, pp 139-148.

[75] Unique Health Identifiers for individuals: A White Paper (1997), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, http://www.epic.org/privacy/medical/hhs-id-/98.htm accessed May 15, 2001.

[76] Federal Register, ‘Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information’; National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics’, Report to the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services on uniform data standards for patient medical record information, 2000, http://ncvhs.hhs.gov/hipaa000706.pdf, accessed November 2000; HHS Fact Sheet, ‘Protecting the privacy of patient’s health information: summary of the final regulation’, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,http://www.os.dhhs.gov/news/press/2000press/00fsprivacy.html, accessed May 2001.

[77] National Research Council, For the Record, Washington D.C: National Academy Press, 1997.

[78] National Privacy Principles (2000), Attorney-General’s Department, Commonwealth of Australia, http://law.gov.au/privacy/royalnpp.pdf, accessed 21 May, 2001.

[79] 'Privacy Legislation', Australian Medical Association, http://www.domino.ama.com.au/dir0103/4236d42a780b68d94a2568850042e3de.html, accessed 24 May, 2001.

[80] Crompton, M., ‘Enhancing privacy and confidentiality in the world of e-health’, Proceedings from the National Health Online Summit, Adelaide, August 2000, pp 35-37, http://www.health.gov.au/healthonline/summit/summit.pdf, accessed 25 May, 2001.

[81] 'Privacy Legislation', Australian Medical Association, supra n.79.

[82] Australian Medical Association comments on proposed Privacy Amendment (Private Sector) Bill (2000), Australian Medical Association, http://www.domino.ama.com.au/dir0103/, accessed 24 May, 2001.

[83] NSW Ministerial Advisory Committee on Privacy and Health Information (2000), A discussion of the Issues, November, http://www.lawlink.nsw.gov.au/pc.nsf/pages/elechealth8 accessed 21 May 2001.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlLawInfoSci/2001/3.html