Melbourne University Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne University Law Review |

|

CHRISTINE PARKER[∗] AND VIBEKE LEHMANN NIELSEN[†]

[Since 1991, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission has actively encouraged, and sometimes forced, Australian businesses to implement internal competition and consumer protection compliance programmes in order to improve compliance amongst a wider range of businesses than can be reached by enforcement action alone. Have Australian businesses implemented the type of internal management systems and controls that the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, industry best practice and research evidence see as desirable for trade practices compliance? This article presents findings from a survey of 999 of the largest Australian businesses (as determined by number of employees) on the extent to which they have implemented trade practices compliance systems. Outcomes from the study demonstrate that, on the whole, the implementation of trade practices compliance systems is partial, symbolic and half-hearted. Nevertheless, enforcement action by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission improves the level of implementation of compliance systems.]

Since 1991, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (‘ACCC’) has prodded Australian businesses to implement internal competition and consumer protection compliance programmes.[1] The aim has been to deepen businesses’ commitment to, and responsibility for, the achievement of the goals of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (‘TPA’), and to improve compliance amongst a wide range of businesses. The ACCC cannot discover, let alone take enforcement action on, every breach of the TPA by a business. But it does expect every business to be its own enforcement agency — identifying, correcting and preventing its own noncompliance. What effect has the ACCC’s strategy had on Australian businesses’ implementation of compliance programmes? Have Australian businesses implemented the type of internal management systems and controls that the ACCC, industry best practice and research evidence see as desirable for trade practices compliance?

In recent times, many business regulation enforcement agencies and policymakers have turned their attention towards trying to change internal corporate management processes and cultures to improve internal corporate commitment to, and achievement of, regulatory goals.[2]

Laws regulating the social and economic responsibilities of businesses now frequently provide that the extent of corporate liability for damages or penalties will depend at least partly on the extent to which corporations have implemented internal systems designed to identify, correct and prevent wrongdoing or liability.[3] Licences and permits in environmental and financial services are now given, and other industry-specific regulation are applied, only after businesses have satisfied the regulator that they have appropriate internal compliance and risk management systems in place.[4] Since the United States’ implementation of the post-Enron reforms pursuant to the Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act of 2002,[5] general corporate regulation is also increasingly requiring implementation of internal compliance controls.[6]

Regulatory reliance on the implementation of internal business compliance systems has, however, been criticised by some commentators as merely an exercise in ‘cosmetic compliance’.[7] It is suggested — and substantial evidence is available to support the suggestion — that companies will implement compliance management systems only to the extent necessary to ensure they look legitimate, or to the extent they are forced to do so. Their management changes will be partial and half-hearted, and courts and regulators will lack the skills and resources to distinguish genuine, substantive and effective compliance commitment from simply ‘ticking the boxes’.[8]

This article presents results from a survey of 999 businesses drawn from the 2500 largest Australian businesses determined by number of employees.[9] This article also draws on the results of an earlier qualitative study which involved semi-structured interviews with 100 ACCC staff, trade practices lawyers, compliance advisers, and business people who have been the subject of ACCC enforcement action.[10] The samples and methodologies for both the survey and the preparatory qualitative study are briefly explained in Part VI(A) below, including analysis suggesting no major non-response bias amongst our survey sample by size or by industry.

In this article, we first briefly describe the ways in which the ACCC seeks to encourage or enforce implementation of compliance systems, and the wider significance of the encouragement of compliance systems as a regulatory policy strategy. Second, we set out the major descriptive results from our survey indicating the extent of implementation of trade practices compliance systems by Australian businesses. We also examine the aspects of compliance systems that are most commonly implemented and the extent to which implementation is influenced by ACCC enforcement activity. Third, we discuss these empirical results to explain what they tell us about the approach to trade practices compliance system implementation adopted by Australian businesses, and whether the strategy of the ACCC of promoting trade practices compliance system implementation has been effective and wise. Finally, the article summarises the conclusions we have drawn from the data generated by the survey. The evidence presented in this article suggests that on the whole Australian businesses’ implementation of trade practices compliance systems is partial, symbolic and half-hearted. But this does not necessarily mean that the ACCC should abandon its strategy of encouraging, promoting and enforcing implementation of trade practices compliance systems by businesses. Indeed we find that ACCC enforcement action does improve compliance system implementation.

The ACCC is the federal competition and consumer law regulator for Australia, responsible for enforcing provisions of the TPA that apply to all Australian businesses. This involves the policing of certain anti-competitive conduct (for example, price-fixing and abuse of market power),[11] unfair trading practices (especially misleading and deceptive advertising),[12] noncompliance with legislated product safety standards, and unconscionable conduct in dealings between businesses and between businesses and consumers.[13] The ACCC has powers only to investigate potential contraventions and to take alleged offenders to court for the imposition of monetary penalties, injunctions and other orders. It has no powers of its own to fine or penalise businesses. Nor does it engage in substantial proactive monitoring of business compliance with the TPA. It is a reactive enforcement agency, usually waiting to receive complaints before taking any action. Indeed the ACCC receives thousands of complaints every year, and investigates only a tiny proportion of these cases. According to ACCC Commissioner David Smith,

in the 2003–2004 financial year the ACCC received 48 724 complaints and inquiries relating to the Trade Practices Act.

Just 634, or 1.3 percent of complaints, were escalated to investigation. 220 then went to serious investigation and only 20 proceeded to litigation. These figures are not atypical of past years as well.[14]

The ACCC has long recognised that it does not have sufficient resources to rely only on enforcement litigation to promote business compliance with the TPA: ‘In the face of these numbers it’s a fact of life that the ACCC does NOT have unlimited resources and therefore needs to be selective.’[15] It has therefore used its enforcement, as well as its educative and liaison activities, to encourage the adoption of compliance systems. In doing so, the ACCC hopes to garner both deeper and wider business commitment to, and achievement of, competition and consumer protection goals than it can accomplish through litigation alone.

First, the ACCC has used its enforcement activity to make businesses implement compliance systems. The enforcement side of the ACCC’s strategy for encouraging implementation of compliance systems is aimed at deeper business commitment to, and achievement of regulatory goals. As Deputy Chair of the ACCC Louise Sylvan has stated, ‘traditional regulatory enforcement strategies (penalties, injunctions, declarations, other orders etc) — despite being a big hit on a company — have not always been able to bring about a lasting change in corporate behaviour.’[16] The ACCC has therefore sought to foster deeper, more substantive changes in business behaviour and commitment by expecting businesses to respond to ACCC investigation or prosecution by the implementation of an internal trade practices compliance system (or review their existing system).

In support of this expectation, the ACCC has successfully argued that a court should take into account whether the defendant business has implemented a compliance system in determining the level and type of penalties and orders to be granted.[17]

The test is that the business must have implemented ‘a substantial compliance program … which was actively implemented’ and that implementation must be ‘successful’.[18] Where there is no evidence to show that this is the case, the penalty will be larger, and injunctions to refrain from future contravening conduct are more likely to be granted.[19]

Where a business does not respond to investigation and prosecution by implementing a compliance programme of an adequate standard, the ACCC has also argued that the court should order the business to do so in order to prevent subsequent breaches. The ACCC has had varying degrees of success in obtaining such orders. However, at the ACCC’s recommendation, the TPA has now been amended to specifically authorise the courts to make ‘probation orders’ under s 86C, which can include orders for the implementation of compliance systems (or parts of a compliance system).[20] Moreover, where the ACCC settles potential enforcement actions through the voluntary agreement of the business under investigation, the ACCC almost always requires the business to implement a compliance system as a condition of settlement.[21]

Each of the ACCC strategies described thus far are aimed at prompting a deeper commitment to compliance amongst businesses that actually come into direct contact with the ACCC. As Sylvan stated, ‘if a company does not have an effective compliance program in place, they most certainly will have one when we catch them.’[22]

We would expect that, if the strategy of the ACCC has been successful, those organisations that have been investigated for breaches of the TPA, and had enforcement action brought against them (particularly those which have been forced to put in place a compliance system as a result of enforcement action), would have a deeper level of commitment to compliance system implementation.

The ACCC has also self-consciously nurtured trade practices compliance skills and standards in Australian businesses in order to promote high quality compliance management more widely than would have been possible through enforcement action alone.

The ACCC has been particularly active in creating a market for trade practices compliance advisory services, fostering the trade practices compliance industry and communicating standards and guidelines to the industry once established. In the early 1990s the ACCC established a Compliance Education Unit, which has since been disbanded,[23] and developed the Best and Fairest Compliance Manual, a model compliance programme and set of training modules for businesses to use with managers and staff.[24] The Compliance Education Unit was also available to act as compliance consultants for companies who had entered into TPA s 87B undertakings or who voluntarily wished to set up a compliance programme. The ACCC was also instrumental in educating and equipping (external and in-house) business lawyers and compliance advisers to help businesses improve their internal trade practices compliance processes. The ACCC helped set up the Society of Consumer Affairs Professionals in Business Australia in 1993 and the Association for Compliance Professionals of Australia (now the Australasian Compliance Institute (‘ACI’)) in 1996. Both organisations grew quickly in membership and status.

Together with the ACI, the ACCC also requested and helped develop AS 3806 on ‘Compliance Programs’ under the processes of Standards Australia.[25] AS 3806 provides a management system standard for ensuring internal regulatory compliance (not just with trade practices law but with any regulatory or self-regulatory obligations) and is widely accepted as the management system standard for compliance in Australia.[26]

It is promoted as such by the ACI, and also adopted by the ACCC and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (‘ASIC’) as a useful guide for compliance systems.[27]

Previously the ACCC had also been involved in initiating and developing AS 4269 (February 1995) on ‘Complaints Handling’ under the processes of Standards Australia. The ACCC has continued to prioritise compliance education and liaison activities through small business and rural and regional outreach programmes, numerous speeches and attendances at meetings, conferences and other fora within businesses, and at industry and professional group meetings. It has also continued to develop and update numerous publications on TPA compliance issues, as well as been involved in developing or reviewing industry codes of conduct.[28]

This set of ACCC strategies is aimed at making it more likely that a greater number of organisations will adopt higher standards in the implementation of compliance systems. The hope is that the deterrent effect of ACCC enforcement activity will have a deeper impact in encouraging a wider range of businesses to implement trade practices compliance systems. The strategy is that when businesses (even those that have not had any direct contact with the ACCC) seek advice, or look for information on how to comply with the TPA (whether from lawyers, consultants, compliance advisers or industry associations), the ACCC will have already ensured that the available information and professional advice all emphasise the need to implement substantial internal compliance programmes of a high standard. As ACCC Commissioner Smith explained:

The ACCC much prefers compliance over confrontation or crackdown. But, having said that, the ACCC also sends a clear message — that message is that we will never hesitate to confront any business or crackdown on any behaviour which flouts the clear obligations all business has to comply with the Trade Practices Act.

We believe it is eminently more sensible to have business comply with the Act, instead of have them act in a way that does damage to both consumers and the business, and then have to try to undo that damage later.[29]

If this ACCC strategy is successful, we would expect to see a wide range of organisations beyond those which have had direct contact with the ACCC implementing substantial trade practices compliance systems.

In order to evaluate whether the ACCC’s strategies have had any impact, we need to know what the ACCC does, and should, expect of business implementation of trade practices compliance systems. What are the standards or benchmarks for these systems? As we have seen, the test that the courts use to evaluate business implementation of trade practices compliance systems is that the business must have ‘a substantial compliance program … which was actively implemented’ and that implementation must be ‘successful’.[30]

AS 3806 provides a more specific set of criteria for best practice compliance programmes.[31] The ACCC also provides detailed guidance as to the features it expects of compliance systems implemented under enforceable undertakings. The ACCC sees its guidance as consistent with AS 3806.[32]

According to these guidance templates, the ACCC expects that the trade practices compliance systems of larger businesses should involve:

• appointment of a director or senior manager with suitable qualifications or experience as a compliance officer, with responsibility for ensuring that the compliance programme is effectively designed, implemented and maintained;

• a risk assessment for potential breaches of the TPA and procedures for managing those risks;

• a policy statement outlining the commitment of the company to trade practices compliance and a strategic outline of how that commitment to trade practices compliance will be realised, including a requirement for staff to report compliance issues and concerns to the compliance officer, a guarantee of protection to whistleblowers, and a statement that the company will take internal action against any persons who are knowingly or recklessly concerned in a breach and will not indemnify them for any external action taken against them;

• a trade practices complaints handling system;

• regular reports from the compliance officer to the board and/or senior management on the continuing effectiveness of the compliance programme;

• regular and practical trade practices training for all directors, officers, employees, representatives and agents whose duties may put them at risk of contravening the TPA, including their incorporation into induction training; and

• regular reviews of the operation and effectiveness of the compliance programme.[33]

This set of requirements is broadly consistent with what scholarly evaluations of corporate compliance programmes find to be effective.[34] Christine Parker has previously argued — on the basis of empirical fieldwork on best practice and a review of the literature — that at the very least a corporate self-regulation or compliance system should encompass the following:

1 That there should be clearly defined responsibility for compliance that is shared between:

• A specialised compliance function (for example, a compliance officer) with clout to determine strategies and priorities for legal and social responsibility issues, monitor compliance, receive complaints from internal and external stakeholders, and be responsible for coordinating reports on the responsibility performance of the company to government agencies and the public;[35]

and

• A clear board-level compliance/self-regulation oversight agenda. This might be achieved by a board audit or compliance committee, a designated board member, or simply by making the compliance/self-regulation programme a standing agenda item on ordinary board meetings;[36] and

• Reporting lines and job descriptions that make compliance part of everybody’s job and construct clear pathways for compliance performance and for problems to be taken directly to the top through a reporting line independent of line management[37]

2 The company should regularly evaluate its compliance processes and performance, including the extent of implementation of self-regulation processes: whether their scope and strategy remains appropriate for the organisation; verification of reports of activity and performance produced internally; and assessment of performance and outcomes of the whole approach to compliance management within the corporation;[38]

3 The internal discipline system of a company must support the compliance system. Management and employees should be regularly and swiftly disciplined for any misconduct under the compliance system (and also be rewarded via performance evaluations for positive contributions). This disciplinary system should be designed in such a way that it respects employees’ integrity, connects with employees’ values and allows the company as a whole to learn from individual mistakes and misbehaviours in order to prevent them from recurring;[39]

4 The company should have a system for engaging with external stakeholders. It should have mechanisms for identifying its obligations under law, and any other standards it wishes to voluntarily adopt (for example, broader human rights principles), and have systems that allow external stakeholders to use these principles to contest corporate actions and decision-making. These should include, at the very least, a complaints handling system with a capacity to both identify patterns of complaint and to report those issues to someone who can resolve them.[40]

The measures of compliance system implementation used in our study are based on this conception of what is required for an organisation to have a substantial, actively implemented and effective compliance system.

No previous systematic studies are available of how widespread trade practices compliance systems are in the Australian business community at present, or of how partial or committed the implementation of these systems might be. Anecdotal and qualitative evidence suggests that most large companies do have a trade practices compliance system in place. For example, submissions to a 1994 Australian Law Reform Commission inquiry on compliance with the TPA suggested that at that stage the high profile of the activities of the ACCC had already led most large companies to renew or implement programmes.[41]

In the qualitative study,[42]

trade practices lawyers reported that they always advised clients who were likely to have any trouble or contact with the ACCC that they should implement or revise a trade practices compliance programme. Indeed, they stated that they generally advised all their clients to implement such a system, and had been providing this type of advice since at least the mid-1990s. Typical comments included:

In the last 10 years companies have realised they need trade practices compliance and a compliance program is at the top of the general Counsel’s agenda.

We basically tell people whether you’re bigger or smaller, the ACCC expects you to have a live compliance program. You need to have a compliance person in place, training (face to face then online training if you can afford it) and a whistleblower policy in place. Then ascertain which people are at a higher risk and concentrate on them for ongoing training. You also need to create a culture where people aren’t afraid to ask questions.[43]

However, implementation of these systems by clients was not necessarily fulsome. A number of lawyers commented that many clients now wanted a trade practices compliance programme, but that their clients rarely bought the full compliance programme services that would actually provide them with comprehensive and effective compliance management. As one lawyer reported: ‘Not too many have really got their heads around the concept of compliance being about good management. Although some of them say that in their rhetoric. They don’t want to spend very much on compliance.’[44] Cost-conscious clients usually just wanted their lawyers to undertake some training sessions, not to conduct thorough evaluations of the management and culture of the business. One lawyer observed: ‘They don’t ask for audits. They just want people to come in as talking heads. Half-hearted is the core thing. You tell them that audit is advisable but they are generally reluctant to spend money.’[45]

Moreover, any new commitment to implementing or revamping a competition and consumer protection law compliance system generally only came about through a brush with the ACCC:

There is no doubt they revamp their compliance programs if they have a brush with the ACCC just as a strategic response … The strategy is that if we’re going to be in trouble, it’s a strategy in minimising the penalty. The companies will ask for a compliance program by and large as a result of an investigation by the ACCC. Very very large corporations will unilaterally ask for an upgrade without a particular matter, but they probably have regular dealings with the ACCC anyway. Beyond that most are reactive.[46]

The qualitative interviews suggested that it was hard to convince clients that they needed to keep their compliance programmes up-to-date in the absence of problems with the ACCC.[47]

The picture painted by these interviews suggests that implementation of compliance systems by Australian businesses is on the whole symbolic, partial and half-hearted. As one lawyer said: ‘We are keen to offer trade practices compliance programs but the companies are truly receptive only after a problem. Most of the companies do have one, what we offer is an upgrade — bells and whistles’.[48] In other words, most companies have a partial compliance system in place. But they do not meet their own lawyers’ standards as to what comprises an effective and committed trade practices compliance system, one with all the ‘bells and whistles’. They tend to think about upgrading the compliance system only when they have a problem with the ACCC. A cynic might argue that these trade practices lawyers are likely to be biased in favour of wanting their clients to buy more services — they might therefore underestimate their own clients’ implementation of compliance systems.[49]

In the following, we shall see evidence from 999 large Australian businesses[50] that, if anything, these lawyers’ views of business implementation of compliance systems might be too optimistic, and that implementation by Australian businesses of compliance systems is even less comprehensive than they suggest.

Businesses with a high level of commitment to compliance and compliance management are likely to need a dedicated compliance role to realise that commitment. Therefore, one simple way of finding out about a business’ level of implementation of trade practices compliance systems is to ask how many trade practices compliance staff they employ. The distribution of our respondents in terms of the number of full-time equivalent compliance staff they employ is shown in Figure 1.[51]

Figure 1: Number of Full-Time Employee Equivalents Responsible for Ensuring Compliance

As can be seen in Figure 1, 114 (13.8 per cent) of the respondents stated that that they had no full-time staff equivalent dedicated to ensuring trade practices compliance. Almost half (373 or 45.2 per cent) had fewer than one full-time employee equivalent responsible for ensuring trade practices compliance, suggesting that trade practices compliance was added on to someone else’s responsibilities for these businesses. Approximately one fifth (170 or 20.6 per cent) of the respondents had one full-time employee equivalent or more, but not two. The remaining fifth (169 or 20.4 per cent) had two or more full-time employee equivalents responsible for ensuring trade practices compliance.

These figures might suggest that trade practices compliance was not considered significant enough to merit a separate appointment in close to 60 per cent of our sample of large Australian businesses. However, while the ACCC and best practice do suggest that a senior person should be ‘made responsible for’ compliance within the organisation, they do not necessarily require employment of full-time staff to manage trade practices compliance. It is also possible that some of the firms that said they had only part-time employees responsible for ensuring trade practices compliance did actually employ full-time compliance managers or lawyers who worked on ensuring compliance with a range of regulatory requirements, not just trade practices compliance (since we specifically asked about trade practices compliance employees). The trade practices compliance system might ‘plug into’ broader compliance arrangements within the organisation. It is more informative to look at the extent to which the businesses have implemented a range of compliance system structures and procedures, not just employment of compliance staff.

The survey asked respondents to provide ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers to a series of 21 very specific questions about whether their organisation had implemented various procedures, actions and behaviours expected to be part of a good compliance system (‘compliance system elements’).[52]

These questions were based on the conception of a good compliance system set out above in Part II(C).[53]

The questions were designed in such a way that it should have been relatively easy for the person filling out the survey to objectively determine whether the answer should be ‘yes’ or ‘no’, eliminating as far as possible the element of subjectivity that makes it easier to respond in a socially desirable way. Table 2 displays the exact wording of each question and also the percentage answering ‘yes’ to each question.[54]

Most elements had been implemented by less than half of the respondents, with two major exceptions. Almost all businesses, 91 per cent, agreed that ‘In my organisation there is a clearly defined system for handling complaints from customers or clients’, and 87 per cent indicated that ‘In my organisation we keep records of complaints from customers, competitors and/or suppliers’.[55] As shown below in Table 1, three quarters of the respondents had implemented one half or less of the elements, and nearly half had implemented only one quarter or less. But only 3.4 per cent of the businesses did not tick ‘yes’ to implementation of any compliance system elements at all (not shown in Table 1). In other words, the vast majority of businesses had implemented some parts of a trade practices compliance system, but had done so partially by implementing only a few of the elements, most commonly complaints handling system elements.

Table 1: Respondents’ Level of Implementation of Trade Practices Compliance System Elements by Quartile[56]

|

Proportion of compliance system elements implemented

|

Survey respondents (%)

|

|

One quarter or less

|

46.2

|

|

One quarter to one half

|

28.0

|

|

One half to three quarters

|

19.6

|

|

More than three quarters

|

6.3

|

In order to better understand the extent to which respondents had implemented trade practices compliance systems, and the elements they more commonly implemented, we used factor analysis (and the literature and best practice on compliance systems described above) to divide the 21 compliance system elements into four groups: complaints handling; communication and training; management accountability and whistleblowing; and compliance performance measurement and discipline.[57] Table 2 below shows the division of the elements into the four groups, the percentages of respondents answering ‘yes’ to each element, and the total mean score for each group.

Our factor analysis indicated that the elements in each group were related —respondents that had implemented one aspect of each group were likely to have implemented more of the other elements in that same group than an element in other groups.[58] Implementation of compliance system elements by firms tended to cluster into implementation of these four different aspects of compliance systems. Moreover, as Table 3 below shows, we found that businesses that had implemented the least commonly implemented compliance system elements (compliance performance measurement and discipline) were more likely to have implemented all the other three groups of compliance system elements than those that had not.[59] Most of these businesses did not implement these elements in isolation, but with most of the other compliance system elements as well. This might mean that for these businesses, implementation of compliance performance measurement and discipline system elements builds upon implementation of other elements. For example, compliance performance could not be measured unless complaints were recorded.

The first and by far the most commonly implemented group of compliance system elements were systems for receiving and handling complaints from customers, clients, competitors or suppliers, or compliance failures identified by people external to the organisation, as well as seeking out consumer opinion on new products and advertising. Each of these elements is concerned with obtaining and dealing with information relevant to compliance from outside the organisation. The respondents’ mean score on implementation of the complaints handling group, calculated using a paired samples ‘t-test’,[60] was significantly different from implementation of the other three, which was fairly poor by comparison.

Communication and training includes all the ways in which the commitment to compliance and specific compliance procedures and practices by the organisation are internally communicated from the senior management down to staff through manuals, training and computer systems. This group also includes an item asking whether the organisation has a ‘dedicated compliance function taking care of trade practices compliance’. This last item fits less neatly with the other items as a measure of compliance communication and training. However, it may fit well statistically with this group of items because they all indicate that the organisation has an explicitly thought-out set of internal policies and communication strategies on trade practices compliance — for that to occur, there must be a dedicated function responsible for doing it.

In contrast with the focus of the communication and training group of elements on top-down communication, the next two groups focus on different ways in which the senior management of the organisation might discover whether management and employees are acting in accordance with the compliance commitment of the organisation, and enforce and improve the organisation’s compliance policies.

Management accountability and whistleblowing includes mechanisms by which individual managers are made accountable for compliance through reporting, as well as through audit or review by external professionals (to check the reliability of reporting). Both compliance reporting requirements and audit or review of the compliance system indicate that senior management actively wants to find out what is happening with compliance among the lower ranks of management. Whistleblowing protections also fit here because they too suggest that senior management wants to be made aware of compliance issues and problems, and is willing to provide guarantees of confidentiality and protection to employees to ensure they are willing to report such issues.

The fourth and least commonly implemented group of compliance system elements are those in the compliance performance measurement and discipline group. This includes two items showing whether the respondent organisations have set specific performance indicators for measuring individual employee and organisational compliance performance. It also includes a question asking whether any employees have actually been disciplined for a compliance breach in the past five years. Responses to this final question should reflect whether the organisation takes its compliance commitment seriously enough to identify and sanction breaches. These three elements clearly fit together as measurements of, and sanctions for, compliance performance.

Table 2: Implementation of Trade Practices Compliance System Elements[61]

|

|

Elements included in each group

|

Answering ‘yes’ (%)

|

Mean level of implementation for group (yes=1,

no=0)

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Complaints handling

|

In my organisation there is a clearly defined system for handling

complaints from customers or clients.

|

91

|

0.57

|

|

In my organisation we keep records of complaints from customers,

competitors and/or suppliers.

|

87

|

||

|

In my organisation there is a clearly defined system for handling

compliance failures identified by staff, competitors, suppliers

or the

ACCC.

|

53

|

||

|

In my organisation we actively seek out consumer opinion about new

advertising and/or new products.

|

40

|

||

|

In my organisation we have a hotline for complaints about our compliance

with the TPA.

|

13

|

||

|

Communication and training

|

My organisation has a written compliance policy about trade practices

compliance.

|

45

|

0.31

|

|

In my organisation employees are now and then sent to a brush-up course on

how to comply with the TPA.

|

38

|

||

|

Live training sessions are a part of our training of employees in trade

practices compliance.

|

34

|

||

|

In our organisation we use a compliance manual in trade practices

compliance.

|

31

|

||

|

My organisation has a dedicated compliance function taking care of trade

practices compliance.

|

30

|

||

|

Induction for new employees includes substantial training in trade

practices compliance.

|

28

|

||

|

At least half our employees have attended an employee seminar about the

TPA during the last five years.

|

21

|

||

|

In my organisation we use a computer-based training program in trade

practices compliance.

|

17

|

||

|

Management accountability and whistleblowing

|

My organisation has written policies to encourage and protect internal

whistleblowers.

|

43

|

0.30

|

|

In the last five years an external consultant has reviewed our compliance

system.

|

35

|

||

|

In my organisation managers are asked to report regularly on

compliance.

|

26

|

||

|

In my organisation we have systematic audits by external professionals to

check for trade practices breaches.

|

17

|

||

|

Compliance performance measurement and

discipline

|

Trade practices compliance performance indicators are included in the

corporate plan.

|

20

|

0.13

|

|

Compliance performance indicators relevant for the TPA are among the

individual performance indicators for our employees.

|

13

|

||

|

In my organisation in the last five years employees have been disciplined

for breaching our trade practices compliance policy.

|

12

|

Table 3: Correlation between Implementation of the Four Groups of Compliance System Elements[62]

|

|

Complaints handling

|

Communication and training

|

Management accountability and

whistleblowing

|

Compliance performance measurement and

discipline

|

|

Complaints handling

|

1.000

|

|

|

|

|

Communication and training

|

0.444**

|

1.000

|

|

|

|

Management accountability and

whistleblowing

|

0.454**

|

0.622**

|

1.000

|

|

|

Compliance performance measurement and discipline

|

0.369**

|

0.527**

|

0.470**

|

1.000

|

In order to better understand the pattern of implementation of trade practices compliance systems by Australian businesses, we also looked at the extent to which implementation of each group of elements varied by reference to a number of factors that might affect the level of implementation.

First, we looked at whether the organisation had been subject to an ACCC investigation for a potential breach of the TPA in the last six years,[63] and if so, whether the outcome of that investigation had included a requirement to implement a trade practices compliance system (or to review and upgrade its existing system).[64] This was because, as we have seen, many of our lawyer interviewees had commented that organisations only implemented or upgraded trade practices compliance systems when they were forced to do so as a result of a close encounter with the ACCC.[65]

Second, we looked at how compliance system implementation varied by the level of organisational awareness of trade practices compliance issues[66] and the trade practices compliance values of management (whether organisational management values tend to support compliance with the TPA or not).[67] We also looked at how implementation of formal compliance management systems correlated with compliance management in practice. Implementation of formal compliance system elements does not necessarily tell us how compliance is actually managed in practice within the organisation. The measure of compliance management in practice asked the respondent businesses to rate to what degree they agreed with 14 specific statements about what business management actually did in order to make sure they complied with the TPA.[68] We see organisational awareness, compliance values and compliance management in practice as each measuring different aspects of ‘compliance culture’ within the respondent businesses. These factors relate to the shared ‘values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies and patterns of behaviors that drive the commitment to and style and proficiency of an organisation’s[69] trade practices compliance management.

Third, we also looked at variation in compliance system implementation by size (measured by number of employees) and industry.[70]

Size should approximately reflect the varying capacity to implement compliance systems.[71] Industry may reflect the probability of compliance scrutiny by the regulator and third parties. It may also reflect differing compliance risks and therefore differing compliance system emphases.

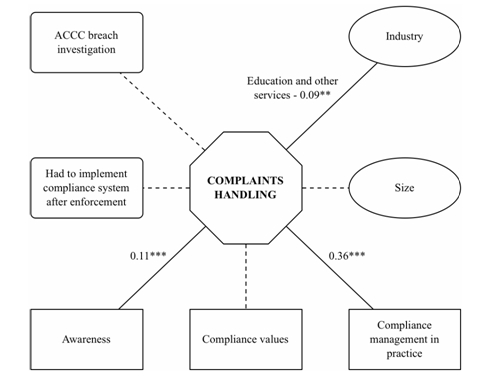

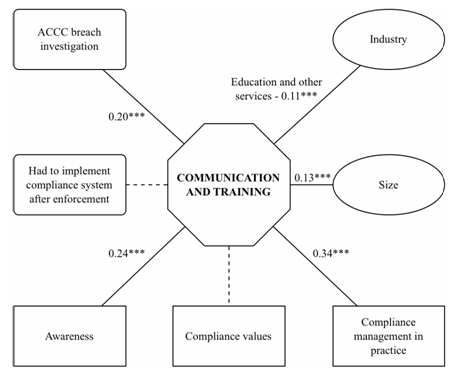

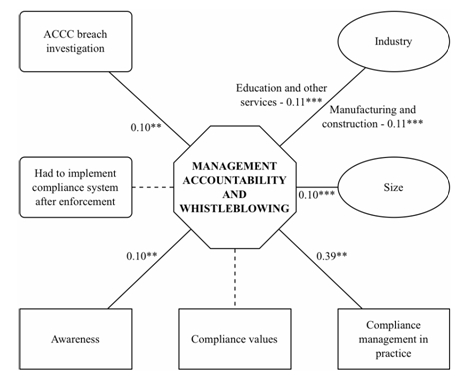

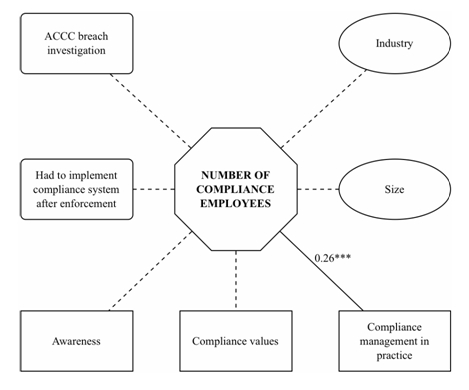

Rather than simply looking for correlations between each of these variables and compliance system implementation individually, it is more informative to use regression analysis to find out how much of the variation in compliance system implementation is attributable to each variable. However, since the level of implementation of each of the four different groups of elements differed significantly, we look at each of the four groups of elements separately. The results are shown as diagrams in Figures 2 to 5.[72] In the diagrams, the solid lines denote the relationships for which the analysis shows a significant positive or negative association. The figures against the lines indicate the relative size, level of significance and direction (positive or negative) of the association between each of the independent variables (around the edge of each diagram) and the dependent variable (in the centre of each diagram). The asterisks represent the extent to which each correlation coefficient is statistically significant, with the more asterisks indicating the more confidence that the result is significant: *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.005; * p < 0.01 (two-tailed). The dotted lines indicate that no significant relationship (positive or negative) was found.

It can be seen that the pattern of implementation of complaints handling system elements was markedly different from the other three. Neither size nor the experience of an ACCC breach investigation was associated with implementation of complaints handling system elements — Australian businesses implement complaints handling systems regardless of these two factors. However, businesses were significantly more likely to have implemented the other three groups of compliance system elements — communication and training, management accountability and whistleblowing, and compliance performance measurement and discipline — if they were larger, and if they had had an ACCC breach investigation.

It was expected that larger organisations would generally have a greater capacity to implement compliance systems more fully, in terms of financial and human resources available for implementation, and also greater access to advice and information on implementation of a compliance system. This appears to be borne out by the findings.

The fact that organisations that had experienced an ACCC investigation were also generally more likely to have implemented more compliance system elements was consistent with the responses received from lawyers in the qualitative research[73] which suggested that businesses only implemented or upgraded their trade practices compliance systems once they had had a brush with the ACCC.

Industry was of little significance, except that businesses in the ‘education and other services’ grouping were significantly less likely to have implemented any of the groups of compliance system elements, with the exception of the performance measurement and discipline elements. These elements were poorly implemented by the other industries.

Compliance awareness, but not compliance values, was positively associated with greater implementation of all four compliance system elements. It should be noted, however, that trade practices awareness might be a result of trade practices compliance system implementation, rather than a cause of it — the data collected from the survey is from one moment in time and it is difficult to determine from it whether compliance awareness causes compliance system implementation or vice versa.[74] The fact that only compliance awareness but not compliance values was positively associated with compliance system implementation for all four groups of elements suggests that ‘compliance culture’ is not very helpful in explaining the level of implementation of compliance systems, if it is taken to mean purely values that are conducive to compliance. However, we did find that compliance management in practice — a measure aimed at the practices and habits of management, not just values and attitudes — was positively associated with greater implementation of all four groups of compliance system implementation.[75]

We also conducted the same regression analysis looking at variation in the number of compliance employees. The results are shown in Figure 6 below.[76] As shown in Figure 1 above, the majority of companies had no more than one compliance employee — 13.8 per cent had no employees. Figure 6 suggests this was true regardless of size, industry or ACCC investigation or enforcement. We might have expected larger companies to be more likely to have more compliance employees than smaller ones, but there was no significant relationship between size and number of compliance employees, probably because most companies had so few compliance employees anyway. Nevertheless, there was a significant relationship between compliance management in practice and the number of compliance employees. Companies with more compliance employees scored higher for their compliance management in practice than those with less or no compliance employees.

Figure 2: Explaining Variation in the Implementation of Complaints Handling (Adjusted R2 = 0.26)

Figure 3: Explaining Variation in the Implementation of Communication and Training (Adjusted R2 = 0.48)

Figure 4: Explaining Variation in the Implementation of Management Accountability and Whistleblowing (Adjusted R2 = 0.32)

Figure 5: Explaining Variation in the Implementation of Compliance Performance Measurement and Discipline (Adjusted R2 = 0.20)

Figure 6: Explaining Variation in Number of Compliance Employees (Adjusted R2 = 0.13)

The results displayed above suggest that implementation of trade practices compliance systems by Australian businesses is partial. Almost all businesses had some sort of consumer complaints handling system, but implementation of the other three elements was very poor, and this was true regardless of size and industry.

The high implementation rate of complaints handling systems compared to the other compliance system elements by Australian businesses suggests that their major focus is on the reactive side of compliance management. Any business that provides products or services to consumers (or even to other businesses) is likely to receive complaints, and poorly resolved complaints can damage business.[77] Putting in place a system to deal with and keep records of those complaints is likely to be essentially a reaction to the fact that complaints have been received.

Even within the complaints handling group of elements, it is the more reactive elements that were more likely to be implemented.[78] Almost all businesses said that they had a ‘clearly defined system for handling complaints’ (91 per cent) and that they kept ‘records of complaints’ (87 per cent). Approximately half (53 per cent) also reported that they had a system for ‘handling compliance failures identified by staff, competitors, suppliers or the ACCC’. However, less than half (40 per cent) said they ‘actively’ sought out ‘consumer opinion about new advertising and/or new products’, suggesting a more proactive approach to preventing consumer complaints before they occurred. Only 13 per cent said they ‘had a hotline in place for complaints about compliance’, an initiative that would tend to actively encourage reporting and frank discussion of potential compliance problems inside the organisation.[79]

The high implementation of complaints handling compliance system elements — particularly the focus on mechanisms for handling complaints from consumers rather than hotlines encouraging internal reporting of potential compliance problems — also suggests that compliance system implementation by Australian businesses is more focused on compliance with the consumer protection aspects of the TPA than the competition provisions. Again, this reflects a more reactive, ‘business case’ focused approach to compliance system implementation. By contrast, ensuring compliance with the competition provisions of the TPA is likely to require a more proactive approach to prevent or expose breaches. Moreover, there is not necessarily any immediate financial or reputational gain for business in avoiding offences like price-fixing, abuse of market power and other anti-competitive behaviour, compared with handling external complaints well.

On the one hand, implementing even ‘reactive’ complaints handling mechanisms is an important first step in taking active internal responsibility for compliance issues, if these mechanisms are used effectively. On the other hand, just because an organisation has complaints handling mechanisms does not necessarily mean that those mechanisms are actively implemented in a way that makes a difference to the way the organisation is managed. Our questions about compliance management in practice tell us more about this. Particularly relevant are the questions asking to what extent respondents agreed that, ‘In my organisation compliance problems are quickly communicated to those who can act on them’, and ‘In my organisation systemic and recurring problems of noncompliance are always reported to those with sufficient authority to correct with them.’ Agreement with these items would suggest that complaints handling mechanisms are achieving their target. As shown above in Figure 2, there is a high correlation between implementation of a complaints handling mechanism and a high score on compliance management in practice. The same is true of all the other groups of compliance system elements.[80] This suggests that the implementation of complaints handling mechanisms and of the other groups of compliance system elements, does have some practical management significance for most businesses.[81]

The three groups of compliance system elements — other than complaints handling — are all more difficult, and probably more costly, to implement than the reactive correction of potential problems identified by complainants. They involve more proactive internal management to identify and prevent misconduct in ways that are embedded in the organisational habits of management. Communication and training, and management accountability and whistleblowing, are the two next most commonly implemented groups of compliance system elements. Compliance performance measurement and discipline, which requires the most proactive and potentially costly action, is the least implemented group of elements.

The single next most commonly implemented compliance system element after the complaints handling system elements was the easiest to implement and most purely symbolic element: this was implemented by 45 per cent of respondents: ‘My organisation has a written compliance policy about trade practices compliance’. Looking at the other elements included in communication and training, it is clear that as the items become more specific and demanding, implementation is lower. Accordingly, 38 per cent ‘now and then’ send employees to ‘a brush-up course on how to comply with the TPA’, but only 28 per cent always include TPA compliance training in their induction for new employees and only 21 per cent could say that ‘At least half our employees have attended an employee seminar about the TPA during the last five years.’[82] ACCC staff often commented that businesses that do not really take compliance management seriously will develop a compliance manual and a training video, or some other sort of training programme, but still say that they have a substantial, active compliance programme in place.[83]

The poor implementation of communication and training elements suggests that the level of compliance system implementation might be even lower than ACCC staff and trade practices lawyers and compliance professionals expected. It also suggests that our questions were specific and objective enough to force respondents to report honestly on how substantial and systematic their compliance communication and training systems were.

Most companies also have a low level of implementation of compliance system elements concerning management accountability and whistleblowing. Unsurprisingly, what little data is available on the implementation of corporate compliance programmes in other jurisdictions also tells us that this is one of the weak spots in current corporate compliance programmes internationally. Alan R Beckenstein and H Landis Gabel found in a 1983 survey of United States antitrust compliance programmes that audits were under-utilised.[84] Similarly, in a 1991 study of compliance efforts of more than 700 United States companies, Jeffrey Kaplan found that 45 per cent had no ethics auditing systems.[85] A survey conducted in 2000 by Barry J Rodger of 141 British companies about their implementation of competition compliance systems found that although 77.3 per cent claimed to have a competition compliance programme in place (as either a specific programme or part of a wider regulatory compliance programme), only 41.1 per cent undertook any evaluation of the programme.[86] In his more in-depth qualitative research with three companies on the same topics, Rodger found that each of the companies researched was ‘weakest … in terms of a comprehensive management system for the compliance programme including a regular formal audit’.[87] By comprehensive management system he means systems for reporting risky behaviour (such as contact with competitors).[88] These are processes similar to those included in our management accountability and whistleblowing analysis.[89]

Business implementation of compliance systems in a range of regulatory arenas is often criticised by academic commentators for taking the easy path of cosmetic or symbolic compliance, and avoiding substantive behavioural change.[90]

It is suggested that senior management will often make a symbolic commitment to compliance in a written statement communicated to staff and external stakeholders. However, they do not necessarily take responsibility for setting management incentives (and sanctions) as well as work procedures within the organisation in a way that promotes compliance — staff are left to work this out for themselves. Indeed, compliance systems may even be used to avoid senior management and entity responsibility for breaches, and/or to shift blame for breaches onto individual employees (workers, line managers or compliance staff).[91]

Critics argue that organisations generally make no substantive changes to their ordinary modus operandi unless they feel compelled to do so by pressure from regulators or elsewhere. In response to this pressure, they will only make symbolic compliance efforts. They will implement formal compliance management systems to the extent that it is easy, absolutely necessary in order to maintain legitimacy, and/or they are compelled to do so by regulators.[92]

As Lauren Edelman et al argue, ‘[o]rganizations … [create] symbolic structures … as visible efforts to comply with law. … [But] because the normative value of these structures … does not depend on their effectiveness, they do not guarantee substantive change’.[93]

Previous empirical studies of the extent of implementation of corporate compliance systems certainly provide some evidence to support this critique. Gary R Weaver, Linda Klebe Treviño and Philip L Cochran conducted a survey of 254 United States ‘Fortune 1000’ firms finding:

a high degree of corporate adoption of ethics policies, but wide variability in the extent to which these policies are implemented by various supporting structures and managerial activities. In effect, the vast majority of firms have committed to the lower cost, possibly more symbolic side of ethics activity: the promulgation of ethics policies and codes. But firms differ substantially in their efforts to see that those policies or codes actually are put into practice by organisation members.[94]

The very poor implementation of compliance performance measurement and discipline elements by respondents tends to confirm that this critique also applies to Australian business implementation of trade practices compliance programmes. In light of this critique it is not surprising that this is by far the least implemented group of elements. The definition and measurement of performance indicators for compliance is more difficult than setting out policies and processes, and communicating and training in compliance. In particular, it is rare for organisations to actually discipline employees for compliance failures. Only 12 per cent of respondents agreed that they had done so in the past five years, the lowest score for any compliance system element in the whole questionnaire. Yet asking respondents whether they had disciplined anyone in the past five years is a good test of how active and well implemented a compliance system they have in place. Similarly, to ask whether they have compliance performance indicators in place is a good way of determining how substantial their compliance management system is, since it is generally recognised that good management of anything requires the measurement of what is done and its impact. Here only 20 per cent of organisations had compliance performance indicators in the corporate plan, and only 13 per cent had trade practices compliance performance indicators for individual employees.

These results suggest that it is still fairly rare for organisations to do any more than promulgate a code or policy of trade practices compliance. Very few actually use a systematic methodology to measure their success in implementing that policy. As can be seen from their implementation of management accountability and whistleblowing elements, it is also fairly rare that they use an external or independent professional to systematically review their performance.

We have seen that the survey results suggest that trade practices compliance system implementation is partial. Does this mean that the promotion of deeper and wider compliance system implementation by the ACCC has been ineffective? Is the regulatory strategy of encouraging organisations to become their own enforcement agents doomed to fail?

The analysis shown in Figure 2 does suggest that ACCC enforcement activity has had little direct impact on the implementation of the most commonly implemented group of compliance system elements — complaints handling.[95] However, ACCC enforcement action probably has an indirect impact on the adoption of complaints handling systems. Apart from the fact that unresolved complaints are likely to lower the reputation of a business with its customers, another reason to implement complaints handling systems is that unresolved complaints might eventually lead to legal action, including complaints to the ACCC that could eventuate in prosecutions. Moreover, the ACCC probably contributed significantly to the diffusion of best practice in complaints handling systems in Australia through its involvement in fostering the development of the Society of Consumer Affairs Professionals in Business Australia, and the complaints handling standard of Standards Australia.

It is clear from the evidence in Figures 3 to 6 that implementation of each of the other three groups of compliance system elements, and also the number of trade practices compliance employees, is positively affected by direct contact with the ACCC.[96] If a firm has experienced an ACCC breach investigation, then it is more likely to have implemented communication and training, management accountability and whistleblowing, and compliance performance measurement and discipline processes and structures. This suggests that ACCC enforcement activity is very important for pushing firms beyond the most commonly implemented compliance system elements — those that are easiest to implement and most symbolic rather than substantive — towards deeper implementation. Firms that experience an ACCC investigation presumably feel compelled to implement or upgrade their compliance systems because the ACCC makes this expectation clear, and because the businesses’ lawyers advise them to do so. One brush with the ACCC can have a lasting impact on improving an organisation’s ongoing compliance management activities.

In relation to communication and training, and management accountability and whistleblowing elements, it does not make any difference whether firms are required to implement or upgrade a compliance system as an outcome of the investigation, beyond having an ACCC investigation. In relation to the group of elements that is least implemented and presumably most difficult and costly to implement — compliance performance measurement and discipline — being forced to implement a compliance system also improves implementation, beyond the improvement that comes merely from being investigated by the ACCC.[97]

Although compliance system implementation is partial overall, our results show that ACCC investigation and enforcement activity is a very important reason for businesses to bother with active implementation of a substantial compliance system at all.[98]

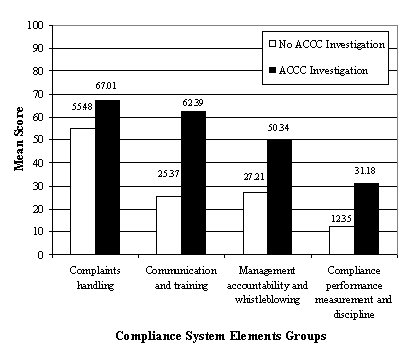

Figure 7 below represents this by comparing the mean level of implementation of each of the four groups of compliance system elements among those respondents who had not experienced an ACCC investigation and those who had. As can be seen, in all four areas, but especially in the three groups other than complaints handling, those who had experienced an ACCC investigation had implemented many more compliance system elements.

Figure 7: Comparison of Implementation of Compliance System Elements

We have already seen that critics of regulatory reliance on business implementation of compliance systems have argued that most businesses are typically likely to implement compliance systems in a partial, symbolic, and half-hearted way. Moreover, we have seen that this does seem to be true of Australian businesses’ implementation of trade practices compliance systems. Critics of regulatory encouragement of compliance system implementation argue that courts and regulators will not be able to adequately specify objective indicators for effective compliance systems, nor will they have the resources to sufficiently monitor their implementation, to be able to distinguish this type of partial, symbolic compliance system implementation from fully committed implementation.[99]

Donald C Langevoort argues that:

it is very difficult to find objective indicators associated with a good compliance program. Of course there can be a checklist of general features of such a program … But these are unlikely to go to the heart of effective compliance, and run the risk of substituting for more careful analysis in such a way that firms gain credit for good compliance simply by introducing an off-the-rack set of visible (but weak) procedures. An in-depth inquiry would require extensive and subjective expert research into the culture and operations of the firm, with severe credibility problems when translated for purposes of adjudication.[100]

Moreover, according to some critics, implementation of a formal compliance management system is in itself a meaningless process that may or may not be effective at producing better compliance. Since we are lacking evidence as to whether compliance systems are actually effective at producing better compliance and, if so, what features of compliance systems are important in improving actual compliance, it may be argued that it will be impossible for regulators to judge effective from ineffective compliance programmes.

Does this mean that regulators like the ACCC should give up promoting compliance systems because they are only likely to be duped by symbolic implementation by most businesses most of the time? The results of our survey do not support this conclusion for a number of reasons.

First, there is a high correlation between compliance management in practice and implementation of compliance systems. The critics may be right that implementation of compliance system elements on their own do not tell us much about the compliance commitment of management, or how it is actually carried out in practice throughout the organisation. However we have seen that, in general, implementation of three of the four groups of compliance system elements (all except compliance performance measurement and discipline) is highly correlated with compliance management in practice.[101] Moreover, we have also found, using the same data set as the results reported here, that compliance management in practice is significantly correlated with better actual compliance on the part of the business respondents.[102]

This suggests that measures of implementation of formal compliance system elements by firms might be a reasonable proxy for assessments of substantial, active implementation of an effective compliance system. This is probably an inadequate substitute for careful, thorough assessments in individual cases. However, in terms of setting standards and objectives for widespread implementation of compliance systems, it is not at all meaningless for a regulator (and courts) to see the implementation of formal compliance systems like those measured here as a sign of good compliance management practice.

Second, in relation to the deeper assessment of compliance systems of individual companies where they are the subject of individual enforcement action, both the ACCC and the courts have shown themselves quite capable of nuanced and sophisticated investigation after the fact. Australian courts have been quite willing to look beyond superficially convincing statements by business people about their compliance commitment, to whether a compliance system that is tailored to the trade practices compliance risks of a company has actually been implemented. Merkel J commented on the evidence presented on this issue in Wizard:

Prior to cross-examination the impression created from Wizard’s correspondence and the evidence given by Messrs Levitt [Wizard’s Head of Marketing] and Malizis [Wizard’s Chief Executive Officer] was that Wizard had implemented and formalised its own trade practices compliance program in accordance with Gilbert & Tobin’s [Wizard’s law firm] recommendations and that it had a fulltime compliance officer who was engaged in supervising that program.

After the cross-examination of Messrs Levitt and Malizis I was left with the impression that the so-called changes in Wizard’s trade practices compliance program lacked specificity and detail. There was said to be a new mandatory legal ‘sign off’ for all television advertising but that was, in substance, meant to be the situation prior to the contravening advertisement. Compliance was said to be a part, albeit a significant part, of the role of the ‘Head of Risk Management’ which encompassed the Privacy Act and the Uniform Commercial Code in addition to the Trade Practices Act. The Head of Risk Management was without legal qualifications. Evidence as to the content of the recommendations made by Gilbert & Tobin was vague and while there was evidence that Wizard’s compliance program was embodied in a written document, that document was not produced to the Court.[103]

As these cases show, the ACCC has also been capable of, and committed to, uncovering evidence of superficial compliance system implementation and presenting it to the court as the basis for penalties and orders. Consider the following extracts from the statements of facts agreed between the ACCC and two of the main defendants in the Queensland Fire Protection cartel case:

Fisher, who was the manager of Tyco’s Queensland and Northern Territory operations, was generally aware that Sproule, Waller and McCormack were attending the meetings, and of the general nature of the arrangement made at the meetings. He did not take steps to stop his employees from attending the meetings until about 1996, when he organised trade practices compliance seminars for staff. Fisher did not encourage or approve the conduct, but acquiesced by failing to take effective steps to prevent it occurring.

ODG and Wormald [the Tyco subsidiaries involved in the cartel] had trade practices manuals but did not have an active trade practices compliance training programme prior to mid-1995. They commenced development of such a programme in 1995. In late 1995 corporate counsel for Tyco conducted trade practices compliance training for its Brisbane managers. Mr McCormack did not attend that training, and continued to attend sprinkler meetings until May 1997. No adequate or proper steps were taken to ensure all managers attended. Those who did attend did not in any case inform the corporate counsel of their conduct.[104]

Similarly, the misconduct of FFE, another member of the cartel, appears to have been unaffected by a compliance programme intended to prevent or stop such conduct:

FFE’s parent company, James Hardie Industries Ltd, began to introduce a comprehensive trade practices compliance training program for its many subsidiaries in late 1993. This included the development of training manuals, seminars, and a computer training module. Corporate counsel for FFE conducted trade practices training for its Brisbane managers in about November 1995. However, none of Messrs Allen, Crosby or Lewis (the managers implicated in the cartel) attended any trade practices training in the course of the conduct. There was no system to ensure attendance at training sessions or that managers had actually read the manuals provided from time to time. Staff were not required to acknowledge or certify that they had not engaged in contravening conduct.[105]

The ACCC and the courts clearly have the capacity to distinguish between superficial and substantial trade practices compliance system implementation when the system has failed and there has been a breach. The difficulty is when the ACCC, or the court, has to assess the trade practices compliance programmes of a company prospectively to see whether they are adequate to protect against breach. This typically occurs where the ACCC has encouraged or required a company to implement (or upgrade) a trade practices compliance system as part of its response to a breach via an enforceable undertaking or a court order. Typically, the compliance system must be approved by the ACCC or meet guidelines established by the ACCC. The ACCC generally requires the company to pay for regular independent third party assessments of their compliance system and its implementation in order to reassure the ACCC and inform management. Parker has previously argued that the processes of the ACCC for reviewing these third party reviews or audits have been inconsistent and often insubstantial, and that insufficient guidance as to the standards expected of the review has been provided.[106]

In response, the ACCC has recently reformed its procedures and the guidance it offers in this area.[107]

The ACI (of which most of the people who conduct these reviews or audits are members) has also responded to concern in this area by setting out protocols for the review or audit of compliance systems.[108] Where the compliance system is to be required by court order, the court has to set out the terms and conditions for an effective, substantially implemented compliance system, something that the Federal Court has not always found appropriate to do by court order.[109]

It seems much more likely that regulators and courts will be ‘duped’ by partial implementation of compliance systems where they are trying to set criteria for effective systems in advance, or when relying on third party reviews of implementation, than when they are conducting in-depth investigations of compliance systems failures in a particular company that led to a particular breach. The recent reforms of the ACCC might improve its record in this area. As we have seen above, the compliance system elements expected by the ACCC do seem to lead to better compliance management in practice, so there is some sense in looking at whether businesses have implemented these elements in assessing their compliance system performance. However, the very fact that compliance systems need to be genuine expressions of trade practices compliance risk assessment and to be tailored to the operational circumstances of each company makes it difficult for courts and regulators to send out clear and consistent messages about the elements that businesses must implement to have effective compliance systems. Nor is it ever going to be easy to consistently assess compliance systems in advance, without an enormous commitment of resources to the task. Genuine compliance systems are particular responses to contextual factors — they cannot be generic. The difficulty of prospective assessment of compliance system effectiveness means that the ACCC and the courts should be especially vigilant and committed to making sure that they rigorously assess compliance systems — after a breach has occurred. To the extent that courts and regulators communicate abstract and generic standards for compliance systems, they are likely to be met with partial implementation. But where they make examples of companies with superficial and inadequate implementation of compliance systems through enforcement action, they demonstrate the importance of genuine commitment in the individual circumstances of each business.

Critics argue that businesses will only partially and half-heartedly implement compliance systems. They will implement only those elements of compliance management that are easy to implement because they are cheap, or because everyone else is implementing them, or because they are forced to implement them as a result of regulatory enforcement action or other stakeholder pressure.[110]

According to this critique, regulatory policies that encourage business implementation of regulatory compliance systems, like those adopted by the ACCC, may look very useful. However, in devoting resources to the encouragement of compliance system implementation, regulators like the ACCC are just colluding in ‘window-dressing’ by businesses that avoids active, substantial and effective compliance management.

Our survey results on the extent of implementation of trade practices compliance systems by Australian businesses certainly show that implementation is overwhelmingly partial and possibly symbolic. Most businesses have implemented some, but far from all, of the compliance system elements considered by the ACCC, practitioners and scholars to be necessary for effective compliance management. Respondents tend to implement the same (relatively few) compliance elements as one another, mainly complaints handling system elements. Those who have experienced a brush with the ACCC are more likely to have put in place more compliance system elements beyond complaints handling. Those who have been forced to implement a compliance system as a result of ACCC enforcement action are also more likely to have implemented compliance performance measurement and discipline elements, which are otherwise the least implemented group of elements.

This evidence shows that commitment to compliance systems by businesses does not occur automatically. ACCC enforcement action is likely to be a very important factor in creating compliance commitment amongst businesses. It is true that most businesses have implemented some form of complaints handling system without a direct experience of ACCC enforcement action. However, it is likely that this was a response to the fear of ACCC enforcement action, or other public or private litigation and reputational damage, should those complaints remain unresolved.[111] The policy question is why Australian businesses seem to feel it is essential to have in place systems to handle and record complaints from customers, competitors and/or suppliers, as a response to the risk of bad trade practices, but do not feel that they must have in place the other more proactive elements of a best practice trade practices compliance system.

We have argued elsewhere that implementation of communication and training, and management accountability and whistleblowing compliance system elements are also important to improving compliance management in practice and actual compliance outcomes.[112]