Melbourne University Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne University Law Review |

|

PAULA GERBER[*] AND DIANA SERRA[†]

[This article provides the first in-depth scholarly examination of the substantive procedural reforms recently implemented in the Technology, Engineering and Construction List (‘TEC List’) of the Supreme Court of Victoria. The authors determine whether the rules governing construction litigation in Victoria represent world’s best practice by comparing them with the rules and procedures of the United Kingdom, which are generally regarded as world leading. The conclusion reached is that while the new rules in the TEC List are a step in the right direction, there is still room for significant improvement in this area.]

The construction industry is known for conflict almost as well as it is known for its most spectacular construction and civil engineering projects.[1]

Approximately seven years ago, Gerber and Mailman asked the question ‘construction litigation: can we do it better?’,[2] and concluded that ‘the time may be right [for Australian courts] to reinvigorate construction litigation by introducing reforms for commercial building disputes’.[3] Since then, the Supreme Court of Victoria has significantly transformed the way in which it manages and regulates construction litigation, including, in 2009, by converting the Building List into the Technology, Engineering and Construction List (‘TEC List’). It is therefore timely to ask the question ‘construction litigation: are we doing it better?’ This question is more important today than ever before, since within the last year, the number of cases initiated in the TEC List has almost doubled, with the list consisting of 32 cases at the time of writing.[4] This article scrutinises the Victorian reforms using a comparative analysis in order to determine whether the Supreme Court’s reforms represent world’s best practice, and ultimately concludes that while the new rules represent a significant enhancement, there is still room for improvement.

In addition to providing the first in-depth scholarly analysis of the TEC List reforms, this article serves a secondary purpose. Renowned American construction law professor Justin Sweet recently lambasted the dearth of scholarly research in the field of construction law.[5] The authors have heeded Sweet’s call for more research in this area, and this article plays a modest role in redressing the problems he identified.

In order to provide context, it is useful to examine the reforms to the rules governing construction litigation in Victoria against the backdrop of other recent reforms to civil procedure rules, and developments in construction dispute resolution generally.

Many of the TEC List reforms were developed during a period when civil procedure rules in Victoria, and nationally, were being overhauled. The modern requirements, imposed by the Civil Dispute Resolution Act 2011 (Cth) and the Civil Procedure Act 2010 (Vic), will have, and indeed are having, a significant impact on potential litigants, alternative/appropriate dispute resolution (‘ADR’) practitioners, and lawyers.[6] The changes reflect a philosophy that litigants should consider and, if possible, use ADR (including negotiation) before commencing an adversarial battle.[7] It has been noted that ‘[i]ncreasingly, policy makers and courts are setting new behavioural standards for litigants, would-be litigants and their representatives and are requiring disputants to meet obligations to resolve disputes before accessing courts.’[8] The new federal and state legislation essentially require that disputants take ‘genuine steps’ (Commonwealth) or ‘reasonable endeavours’ (Victoria) to resolve their differences before commencing litigation.[9]

When introducing the Victorian legislation, then Attorney-General Rob Hulls indicated that the ‘bill’s intention is to give real meaning to the saying that litigation should be a measure of last resort.’[10] Policymakers and members of the judiciary endorse this view of the role of litigation, with then Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia, Murray Gleeson, stating:

Access to justice has a much wider meaning than access to litigation. Even the incomplete form of justice that is measured in terms of legal rights and obligations is not delivered solely, or even mainly, through courts or other dispute resolution processes. To think of justice exclusively in an adversarial legal context would be a serious error.[11]

The recent legislative reforms represent a continued evolution in the use of ADR in Australia, and recognise the changing role of the courts within the modern Australian dispute resolution environment. This will undoubtedly affect construction disputes in a meaningful way.

In her article ‘Judging the Vanishing Trial in the Construction Industry’, Beverley McLachlin noted that

[t]he trend is clear: fewer and fewer construction cases are reaching the courts where the law is developed. Increasingly, instead of being resolved by judges, construction disputes are being sent to mediation, arbitration, or other forms of alternative dispute resolution …[12]

Warren Winkler, the Chief Justice of Ontario, attributes the general trend away from litigation to the fact that ‘[o]rdinary litigants simply can’t afford to take their cases all the way through trial’.[13] Parties to construction disputes are focused on a speedy, low cost resolution, rather than developing the common law.[14] The fact that an increasing number of parties are eschewing construction litigation makes the TEC List reforms even more important. If construction litigation is not perceived as a viable form of dispute resolution, then the construction lists within courts may suffer a similar fate to the dinosaurs. The TEC List reforms represent the Victorian Supreme Court’s efforts to counter the vanishing trial phenomena by making construction litigation a more attractive form of dispute resolution.

John Uff notes that in the last few decades, there has been significant growth in the variety of dispute resolution avenues available to parties involved in construction disputes.[15] However, there is likely to be a place for construction litigation in the smorgasbord of dispute resolution procedures, because there will always be those cases that can only be resolved through the imposition on the parties of a final and binding decision. Uff contends that effective dispute resolution should strive to be final, albeit subject to some exceptions.[16] Thus, for the TEC List to be an attractive option for parties to a construction dispute, the parties must have confidence that the decisions made during the course of the litigation will not be subjected to multiple challenges. Uff notes that the Technology and Construction Court (‘TCC’) in the United Kingdom (‘UK’) ‘has now settled into a much more mature role’ where its decisions are generally accepted by the parties as being as binding as decisions of other divisions of the High Court.[17]

The overwhelming majority of construction projects are undertaken using a standard form contract, albeit one that is often heavily amended. Such contracts generally seek to limit the number of disputes and establish dispute resolution regimes, including the insertion of compulsory arbitration clauses, for those disputes that the parties have not been able to avoid or resolve themselves. Justice Byrne refers to the ‘contractual provisions which seek to confer finality on the determinations of contract administrators, particularly determinations with respect to progress certificates, contractual discrepancies, time extensions and the like’ as being one of the most important dispute minimisation/resolution strategies.[18]

Other contractual provisions designed to minimise and resolve disputes include requiring claims to be made as they arise, so as to avoid unwieldy global claims at project completion, and more novel approaches such as ‘provisions for mini-trials and for negotiations at CEO level.’[19]

Unfortunately, the most widely used standard form contract on Australian commercial construction projects (AS4000) fails to include any form of ADR;[20] it provides only for arbitration or litigation.

The traditional response to the risk of construction disputes has been to include arbitration (compulsory or optional) within the dispute resolution clause of standard form contracts.[21] Courts have tended to endorse this course of action by readily staying litigation if one of the parties seeks to arbitrate the dispute pursuant to a valid arbitration clause in a construction contract.[22] However, despite this support, these days parties in a dispute are less inclined to choose arbitration as their preferred dispute resolution method. Justice Byrne suggests that this is because ‘lawyers hijacked the arbitration process’ and ‘were uncomfortable with disputes involving large sums being determined by those whom they saw as legal amateurs.’[23] His Honour states:

Trained in a forensic environment of some formality, these lawyers insisted that arbitrations be conducted as litigation. In this they derived some support from some judicial decisions which required arbitrators, at least in formal arbitrations, to follow the normal court procedures of openings, cross-examination of witnesses and final addresses, and which required comprehensive reasoned judgments. Decisions of the courts, too, made it difficult for an expert arbitrator to know to what extent his or her own expertise might be used. … The consequence of this has been that lawyers themselves have taken a seat on the arbitral bench. And so the process becomes entirely lawyer-driven. This has meant for the disputants that arbitration tends to be just as formal, lengthy and expensive as litigation — even more so because the lawyer arbitrator lacks the coercive clout of a judge.[24]

The use of arbitration declined further after the introduction of s 55 of the uniform Commercial Arbitration Act, which had the effect of removing the compulsory character of the ‘Scott v Avery clause’ for domestic arbitrations.[25] Section 55 allowed a party who wished to litigate a dispute, to avoid compulsory arbitration, unless the court imposed a stay under s 53 of the Act.[26] Section 55 of the superseded uniform Commercial Arbitration Act has not been replicated in more recent commercial arbitration legislation. Thus, s 8 of the Commercial Arbitration Act 2011 (Vic) mandates that parties must arbitrate their dispute if there is a valid arbitration agreement, and cannot elect to proceed in the courts as an alternative to arbitration.

Another legislative provision which has had ‘far reaching consequences’[27] for arbitration in Victoria is s 14 of the Domestic Building Contracts Act 1995 (Vic), which provides that any arbitration clause in a domestic building contract is void. As a result, all domestic building disputes must now be determined by the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (‘VCAT’).[28] Justice Byrne observes that the consequence of these legislative changes ‘has been to deprive arbitration in this State of a most useful training ground for young arbitrators so that the number of experienced arbitrators has become somewhat depleted over the years’ and that, for this among other reasons, ‘in the domestic context, arbitration has suffered a decline in importance.’[29]

This decline in the use of arbitration does, of course, make litigation reforms even more important, since litigation is likely to be more frequently pursued.

Construction litigation ‘enjoys’ an unenviable reputation for being highly complex, extremely time-consuming and prohibitively expensive. Nowhere were these characteristics more evident than in the infamous case of SMK Cabinets v Hili Modern Electrics Pty Ltd (‘SMK Cabinets’),[30] which involved a claim for damages for defective work and delays arising from the installation of cupboards. Brooking J described the long-running saga that was this case in the following terms:

The notice of dispute was followed by a preliminary hearing at which pleadings were directed; and points of claim led to defence and counterclaim, which itself provoked reply and defence. Then the hearing began, two of the pleadings being amended and a schedule of questions being agreed upon. The hearing, which included a view, lasted some six days. As if this was not enough, after the hearing each side resumed the offensive with written arguments, followed by written submissions in reply. The arbitrator rose to the occasion by making an award that ran into 108 pages. That was in August 1981, and that should have been enough. But by now the Juggernaut was quite out of control and it careered into the Practice Court on a motion to set the award aside. The Practice Court could not contain it, so off it went to the miscellaneous causes list, where it was reinforced by a summons seeking leave to enforce the award. A reserved decision followed after a two day hearing, and four days after that decision still more argument was heard. Then an order was made setting aside part of the award and so, by way of remittal, the Juggernaut went rumbling back towards the arbitrator. It has now been deflected into this Court by way of application for leave to appeal. I for one am not in the least disposed to let it go on its way again if, consistently with legal principle, it can be finally restrained. In listing the steps taken I have not mentioned at least three other interlocutory applications which have served to swell the costs.[31]

As this case so clearly illustrates, construction litigation all too often embodies the excesses of litigation for which the civil procedure system is so frequently criticised. Although SMK Cabinets took place over 25 years ago, not a lot has changed. Construction cases continue to turn into epic sagas, as evidenced by the case of Kane Constructions Pty Ltd v Sopov, which involved a project that commenced in 1999,[32] had judgment at first instance handed down in 2005,[33] and was only finally disposed of in 2009, when the High Court, for the second time, refused an application by the principal for special leave to appeal from the Victorian Court of Appeal.[34] The end result was that the litigation was not finalised until a decade after the date for completion of the project (which was programmed to take only 130 days).

Construction litigation usually involves complex technical issues, several parties (whose involvement typically raises intricate proportionate liability issues) and a large volume of discoverable documents. These aspects of construction litigation all significantly increase the potential for lengthy delays and disproportionate costs. Such an outcome is well illustrated by the SMK Cabinets case, which arose out of a contract for $2000 worth of work, involved a claim of approximately $10 000, and resulted in the arbitrator awarding the respondent the princely sum of $386.50.[35] Thus, it may be seen that construction litigation has a tendency to magnify any deficiencies in the rules of civil procedure.

It is in the nature of construction litigation that its resolution may require technical evidence. Put simply, construction disputes tend to revolve around issues of quality, time or money, and all of these generally require expert evidence. Thus, an architect or engineer may be needed to establish that work is defective (ie not in accordance with the contract or building codes), and ‘the preparation of delay claims often requires input from commercial managers (quantity surveyors), schedulers, site managers, external claim consultants and estimators’.[36] It is a rare construction case that can be resolved solely by lawyers and lay witnesses of fact, if indeed any such cases exist at all.[37] As Paul Newman states:

The involvement of technical experts to provide an independent and dispassionate analysis is essential. Even if lawyers still represent the single largest item of expenditure in most construction litigation, increasingly not so far behind in terms of cost, are the various expert witnesses.[38]

More often than not, construction litigation involves more than two parties, all of whom perform a role in completing the work.[39] Examples of parties other than the builder and owner who could be involved are ‘the contract administrator, insurer, subcontractor, consultants such as an engineer, architect or quantity surveyor and statutory authorities.’[40] These parties each have different interests, claims and potential liability, all of which may need to be explored before a construction dispute can be resolved. It is axiomatic that with the involvement of more parties comes a corresponding increase in the time required to examine the merits of each claim and defence, the number of experts needed, the length of the hearing and, ultimately, the costs.

Construction litigation invariably involves an excessive number of discoverable documents. This arises from the fact that construction projects produce voluminous documentation, including multiple subcontracts and supply agreements, and drawings for every aspect of the construction (architectural, structural, mechanical, electrical and plumbing are just some of the different drawings produced for even a simple house construction). In addition, there tend to be multiple revisions to drawings, daily emails between the numerous parties, diary notes, minutes of site and project meetings, variation requests and orders, and invoicing and payment documentation. Sorting through this documentation as part of the discovery process requires a considerable amount of time, and therefore considerable expense. It is difficult to minimise this expense, since there will be highly relevant information among this sea of documentation, although much of it will be highly technical and difficult for a lawyer to evaluate without an expert to act as ‘interpreter’.[41] Indeed, it has been observed that ‘[d]ocuments from the contractor are often undecipherable to one not familiar with the vernacular and customs of the construction industry’, and that, even to those with this ability, being able to identify the issues within the documentation often ‘requires the interaction of many separate and distinct relationships involving different responsibilities and often unique customs.’[42] Unfortunately, these factors are not limited to disputes arising out of large construction projects, and ‘[e]ven a small construction dispute may require big-case discovery.’[43] Thus, the technical nature of the documents, combined with the sheer volume of material, renders discovery in construction cases a task that should only be undertaken by the rich and brave.

The creation of the TEC List was in response to the time and cost associated with construction litigation, which had been a source of much debate.[44] For example, in an article on the costs of litigation in construction cases, Liz Porter of The Sunday Age highlighted one case[45] involving several months of litigation, the final costs for which a legal source speculated could eventually reach $50 million — a cost far exceeding the value of the claim.[46] The unique nature of construction disputes has meant that construction litigation has

been bedevilled by complexity and detail, interlocutory proceedings have been tortuous and slow, trials have been long and expensive, the real issues have often emerged only during the course of the trial and parties, often both of them, have been disillusioned.[47]

These criticisms are echoed through the various commentaries relating to construction litigation,[48] along with cynicism towards the idea that anything will change in the near future. It was against this backdrop that the TEC List was introduced.

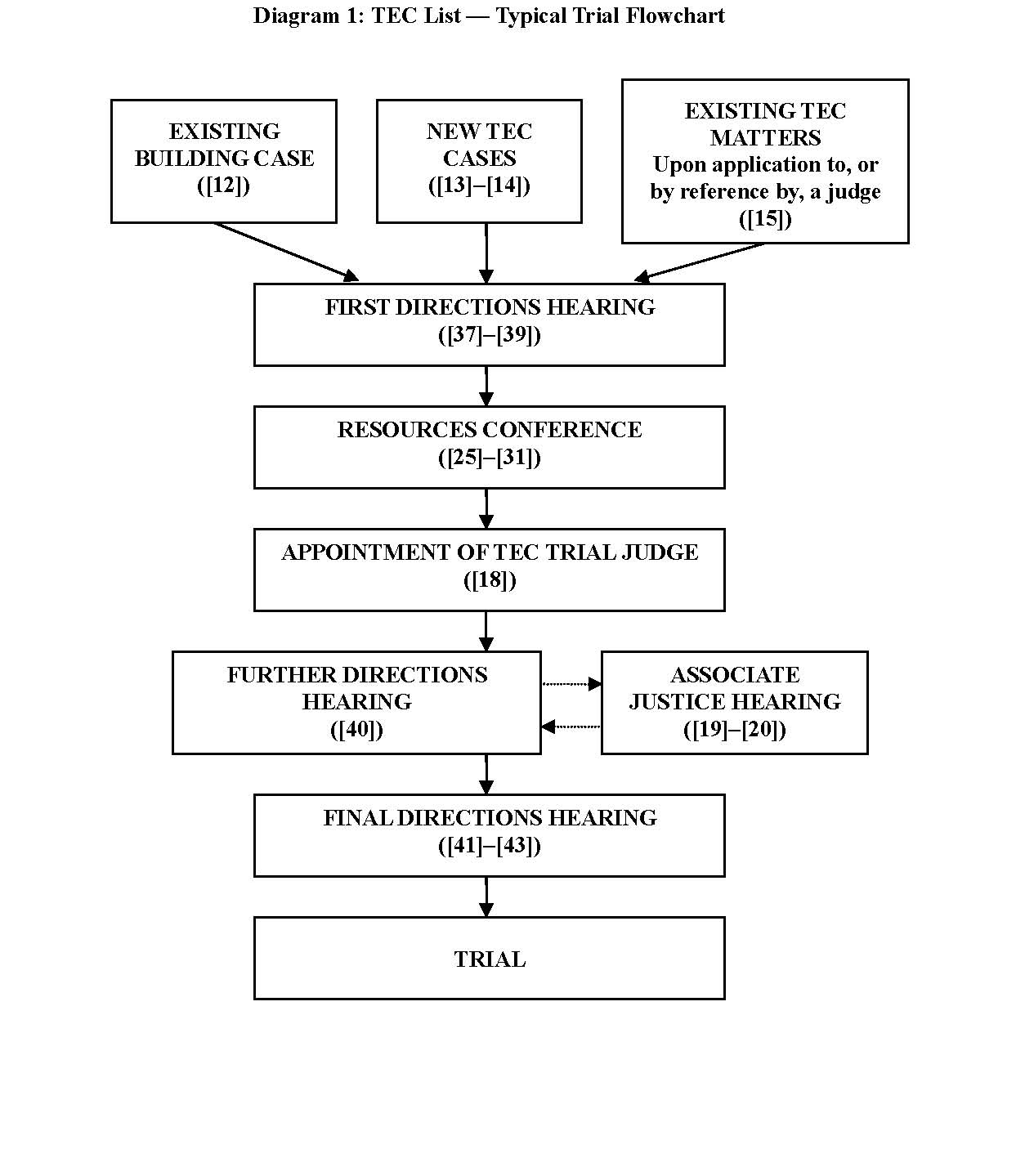

In June 2009, the Supreme Court of Victoria replaced the Building List with the TEC List.[49] Many of the TEC List reforms built upon the work of Justice David Byrne in the development of Practice Note No 1 of 2008 — Building Cases — A New Approach (‘Practice Note 1’).[50] This Part examines the most radical reforms introduced with the TEC List,[51] in order to determine whether they represent a significant improvement in the way that construction litigation is conducted in Victoria. The introduction, in 2009, of Practice Note No 2 of 2009 — The Technology, Engineering and Construction List (TEC List) (‘Practice Note 2’) means that a construction case will typically be conducted as shown in Diagram 1.[52]

Many of the reforms introduced with the TEC List were modelled on the practices of the UK TCC, which have, over the years, reduced, but not eliminated, the British construction industry’s reliance on litigation as the primary method of dispute resolution. However, as the recent high-profile case of Multiplex Constructions (UK) Ltd v Cleveland Bridge UK Ltd[53] illustrates, ‘[i]t is not possible to case manage a case into resolution if the parties themselves insist on a judicial determination.’[54] David Levin notes that even where a case is well regulated, apparently non-commercial and disproportionate outcomes can occur, although it can often be difficult to know what is really at stake for each party.[55] While the TCC reforms may not have ended up being ‘the holy grail of ultimate efficiency’ in England, they have led to ‘real and significant cultural changes’ within the legal profession.[56] It is therefore useful to compare the TCC processes and outcomes, to gain insight into how the new TEC List procedures might impact on construction litigation practices and culture in Victoria.

The most far-reaching reforms introduced as part of the TEC List can be divided into nine categories:

1 the introduction of an objective;2 increased judicial case management;

3 the implementation of resources conferences;

4 changes to the way discovery is undertaken;

5 the management of expert witnesses;

6 the new power to order the parties to prepare a Statement of Issues;

7 the discretion to conduct chess-clock hearings;

8 the introduction of a new electronic case management system; and

9 increased powers when it comes to costs orders.

Each of these is analysed below.

The objective of the TEC List is to provide for the just and efficient determination of TEC cases, by the early identification of the substantial questions in controversy and the flexible adoption of appropriate and timely procedures for the future conduct of the proceeding which are best suited to the particular case.[57]

This objective, like those in the new Civil Procedure Act 2010 (Vic) and the Civil Procedure Rules 1998 (UK) (‘CP Rules’)[58] (both discussed below), contains references to the outcome being ‘just’ or ‘fair’, which make it clear that while the objective is built on notions of ‘cooperation rather than conflict’,[59] with a view to increased efficiency, this is not to be at the expense of justice. The TEC List’s objective requires that disputes be ‘approached by the parties, the lawyers and the Court with particular attention to time and cost and to the budgeting of both.’[60] However, Levin questioned Practice Note 1 (the forerunner of Practice Note 2), which stated that parties should approach construction litigation like a building project. Levin argues that

[b]uilding projects may be initiated with time and cost budgeting, with all parties working towards a profitable outcome and with goodwill and understanding. But when the relationship breaks down and the parties fall out they will not act sensibly nor in a manner which we, as legal representatives, might consider commercial. Each party wishes to have its way; each is able to assess risk and is prepared to gamble on an outcome which suits its immediate and long-term commercial ends. It is foolish for the Court to believe that only it can identify the best commercial outcome for clients whose frame of vision is far broader than the immediate litigation.[61]

Following this pessimistic but arguably accurate description of the inherent flaws of the adversarial system, and taking into account the backdrop mentality that ‘winning is everything’,[62] it is questionable whether the TEC List, by adopting the objectives of efficiency and cooperation, will be successful in overcoming adversarial attitudes.

The Civil Procedure Act 2010 (Vic) provides that ‘the overarching purpose of this Act and the rules of court in relation to civil proceedings is to facilitate the just, efficient, timely and cost-effective resolution of the real issues in dispute.’[63] In order to achieve this overarching purpose, the Act provides detailed overarching obligations for litigants. It establishes a paramount duty to the court to further the administration of justice,[64] and requires that litigants

• act honestly;[65]

• not make claims without proper basis;[66]

• only take steps that they reasonably believe are necessary to resolve or determine the dispute;[67]

• cooperate in the conduct of civil proceedings;[68]

• not mislead or deceive;[69]

• use reasonable endeavours to resolve disputes;[70]

• narrow the issue in dispute;[71]

• ensure costs are reasonable and proportionate;[72]

• minimise delay;[73]

• disclose the existence of critical documents;[74] and

• not use information and documents disclosed under the overarching obligation in s 26 for purposes other than in connection with the current proceeding.[75]

The TEC List reforms include a provision empowering the Supreme Court to penalise a person who has contravened the overarching obligations by making an order that that party pay the other party’s costs and other losses arising from the contravention, and that the party take, or refrain from taking, specified steps in the proceeding.[76] This power may have the effect of motivating parties to make genuine efforts to comply with the overarching obligations.

The use of overriding objectives is not without precedent, as the TCC in the UK is governed by the overriding objective set out in the CP Rules, which provides ‘a compass to guide courts and litigants and legal advisers as to their general course.’[77] The reforms brought about by the CP Rules were based on the 1994 Woolf Inquiry, which involved two years of wideranging consultation with lawyers, experts and court users through public seminars, private meetings and working groups to identify and analyse the main hindrances affecting the system. Lord Woolf devised a coherent scheme for achieving the necessary reforms, which were embodied in the CP Rules — the first complete rewrite of civil procedure in 120 years.[78] Lord Woolf identified the cause of high litigation costs as being not so much the complexity of the procedures as ‘the uncontrolled nature of the litigation process’.[79] In contrast to the quite general objective of the TEC List, the overriding objective of the CP Rules is very detailed[80] — it is to ‘[enable] the court to deal with cases justly’[81] and includes, so far as is practicable:

(a) ensuring that the parties are on equal footing;

(b) saving expense;

(c) dealing with the case in ways which are proportionate —

(i) to the amount of money involved;

(ii) to the importance of the case;

(iii) to the complexity of the issues; and

(iv) to the financial position of each party;

(d) ensuring that [the case] is dealt with expeditiously and fairly; and

(e) alloting to [the case] an appropriate share of the court’s resources, while taking into account the need to allot resources to other cases.[82]

This overriding objective has been hailed as ‘a useful and fundamental source of guidance for the operation of the system as a whole’ and an essential part of the reforms in the UK.[83] It is debatable whether or not such aspirational statements actually stimulate change in the way parties conduct litigation;[84] however, the point has been made that the Woolf reforms, which underpin the overriding objective, have ensured that litigation is conducted with ‘far more co-operation between parties than there was before 1999.’[85] It is hoped that the TEC List’s objective will similarly lead to a cultural shift in the way construction litigation is undertaken in Victoria.

The TEC List reforms allow judges to adopt a more interventionist approach to the litigation process and to controlling the conduct of legal representatives, through a variety of new procedures. These procedures involve judges

• being more ‘pro-active in exercising their powers to achieve a just resolution of … cases in a speedy and efficient manner’;[86]

• ‘assum[ing] responsibility for the management of the case’;[87]

• encouraging legal practitioners ‘to focus on the central issues in the case’;[88]

• expecting parties ‘to have engaged in serious settlement discussions before the commencement of the proceeding’;[89]

• requiring that parties compile a Statement of Issues that summarises their pleadings;[90] and

• limiting the time allowed for the trial.[91]

This increased judicial case management in the TEC List mirrors the TCC reforms in the UK, which recognised that construction litigation required a more systemised approach. Enhanced case management by the TCC has been essential to ensuring that parties concentrate on the most significant issues and that they, and their lawyers, do not ignore the high costs of pursuing litigation or allow the costs to become disproportionate to the size of the claim.[92]

Notwithstanding its benefits, case management does challenge the traditional adversarial paradigms and provoke a re-examination of the rigid procedural requirements, which are relaxed to allow for greater ‘disclosure, transparency, expedition, cooperation and consensus.’[93] Arguably, a ‘vigorous promotion of court-initiated applications will raise the concern of perceived bias by the court in its use of the sanction.’[94] The traditional role of the judge as passive arbiter is ‘central to our understanding of the adversarial system of justice.’[95] The traditional model is ‘said to protect the impartiality and deliberative skill of the judge as it emphasises independence and neutrality.’[96] It has been noted that since active case management obligations were introduced in the UK, the ‘judge in the civil courts is an active case manager rather than a remote and passive umpire.’[97] While this observation is certainly valid, Justice Pagone has observed that it is the role of the judge managing a case to ensure

that management does not pre-empt decision making by proceeding down a path which may be quick and efficient but is achieved at the cost of unfairness to the losing party and at the cost of loss of integrity for the system.[98]

Another important narrative that emerges if the adversarial paradigm is challenged and too much emphasis is placed on managerial judging is that ‘[o]ne might be forgiven for thinking that the performance of the judiciary is evaluated more by reference to how they administer an efficient system rather than on substantive outcomes.’[99] This is a valid concern, and judges must be constantly vigilant to the risk that greater case management comes at the expense of justice. However, ‘the achievement of the right result needs to be balanced against expenditure of time and money needed to achieve that result’.[100] Time will tell whether the granting of greater case management powers will enable TEC List judges to strike such a balance.

Lord Justice May, a UK judge with considerable experience in construction matters,[101] raised another valid criticism of case management when he noted that ‘no amount of legislation or exhortation can make unreasonable people reasonable’; however, he went on to state that ‘Court control can require procedural co-operation and diffuse silly disputes.’[102] The TEC List procedural changes that provide for greater judicial intervention are likely to improve the conduct of construction litigation in Victoria, provided judicial officers exercise their discretion to use these new powers.

The resources conference, a new feature in the TEC List, is convened by the judge in charge of the TEC List at an early stage after the pleadings are closed, for the purpose of establishing

a resources budget for the litigation for the use of both the Court and the parties. The outcome will assist the Court in appointing the TEC trial Judge and allocating a trial date. The conference will also identify issues for mediation and the information and investigation required to enable effective settlement discussions to take place at the earliest possible opportunity.[103]

The resources conference is chaired by an associate judge,[104] and in appropriate cases part of the conference may be conducted on a without prejudice basis, and with the judge speaking separately with the parties.[105] The resources conference is designed to facilitate the adoption of

procedures which are proportionate to what is at stake in the dispute by reference to such matters as: the amount of money involved; the importance of the case to the parties and generally; the complexity of the issues; and the financial position of each party.[106]

At the resources conference, a judge may consider whether any limit should be placed upon resources in terms of trial time[107] and discovery or other interlocutory steps.[108] Prior to the commencement of the resources conference, the parties are ‘expected to have [convened and] engaged in serious settlement discussions’,[109] and the conference will provide an opportunity for the parties and the judge to ‘identify issues for mediation’ and what further ‘information and investigation [is] required to enable effective settlement discussions to take place at the earliest opportunity.’[110]

The concept of a resources conference has been welcomed by the Victorian Law Reform Commission (‘VLRC’), which notes that ‘many [formal] interlocutory steps, including directions hearings, focus primarily on procedural steps directed towards the ultimate trial’, and a resources conference may provide ‘an alternative method by which the parties may endeavour to reach agreement on the steps required for the conduct of the action’ before engaging in a more adversarial setting.[111]

A resources conference involves an early meeting (after pleadings have closed) that is presided over by a Master and is attended by the parties and their lawyers.[112] The idea of a resources conference comes from the TCC’s case management conference (‘CMC’).[113]. The success of CMCs in the UK was highlighted by the Victorian Bar, which, prior to the TEC List reforms, suggested that consideration ‘be given to adopting a similar procedure in the Supreme and County Courts.’[114] The Victorian Bar identified one of the benefits of CMCs as being ‘[t]he early involvement, direction and supervision of the litigation process by the Court’[115] and considered that ‘well-directed case management will be instrumental in reducing overall delay and costs in the civil justice system in Victoria.’[116]

Resources conferences have the potential to increase access to justice and reduce costs. However, the VLRC has expressed some concerns regarding their operation:

First, there are resource implications if … conferences require more judicial officer time than the customary methods for giving directions for the conduct of proceedings. Second, judicial officers may require additional training. Third, given that some parts of the conference may be conducted on a ‘without prejudice’ basis, it will be necessary to use judicial officers other than those who may preside at the ultimate trial of the matter. Fourth, [there is the risk that] cases [may be] over managed. The introduction of further procedural steps may add to the costs borne by the parties.[117]

Despite these potential problems, ‘there appears to be considerable support for the greater use of [resources] conferences’[118] from both the Victorian Bar and the VLRC.[119]

Discovery is a fundamental component of the adversarial system,[120] but also one that is extremely time consuming and costly, and it is for this reason that a significant number of the TEC List reforms relate to the way in which it is conducted.[121] While the use of computers and the power of electronic technology is an enormous advantage on construction projects, it also has the capacity to generate an excessive volume of documents. Justice Vickery has stated that even on medium-scale projects, the creation of between 13 000 and 14 000 emails is not uncommon,[122] and this has obvious implications for any subsequent litigation. Justice Vickery noted one case, recently heard in the TEC List, where the parties proposed that 2.7 million documents would be discovered.[123]

The TEC Discovery Project commenced in March 2009, in response to the problems associated with electronic discovery and the fact that discovery is prone to abuse. The TEC Discovery Project involved a review of the case management powers of courts in Australia and the UK, and the control mechanisms in place in those jurisdictions in relation to discovery. Following this analysis, two new TEC List discovery practice notes were developed. One narrows the test for discovery[124] and the other creates a system of discovery by way of an opt-in electronic ‘dump’ of documents.[125] Each of these is analysed below.

In the past, discovery in the Building List in the Victorian Supreme Court was conducted in accordance with the rule in Compagnie Financiere et Commerciale du Pacifique ν Peruvian Guano Co, in which it was held that documents are discoverable not only if they are directly relevant to the matters in issue, but also if they are indirectly relevant, that is, if they may fairly lead the party seeking discovery ‘to a train of inquiry’.[126] This has been interpreted as meaning that virtually all documents relating to the subject of the litigation are discoverable.[127] The burden of such general discovery interpretation was evident in Trade Practices Commission v Santos Ltd,[128] where the process of discovery lasted for approximately one year. Justice Heerey observed, when reflecting on that case, that

[d]iscovery, including inspection, consumes vast amounts of time and money. It tends to generate numerous disputes over issues like privilege and confidentiality which can become ends in themselves. In the present case it may have been a mistake to have a general, unqualified order for discovery.[129]

The Supreme Court has the power to limit discovery pursuant to Supreme Court (General Civil Procedure) Rules 2005 (Vic) r 29.05, which provides that ‘the Court may … order that discovery by any party shall not be required or shall be limited to such documents or classes of document, or to such of the questions in the proceeding, as are specified in the order.’

Despite judges having the power to specifically limit discovery pursuant to the above rule, an order for Peruvian Guano level discovery ‘is invariably made’, even if a judge has inquired into the need for comprehensive discovery.[130] It is for this reason that the Supreme Court has attempted to further clarify its expectations regarding discovery by way of the TEC List Standard Operating Procedure No 3 of 2009 (‘SOP 3’), which provides for ‘standard disclosure’ of documents that the parties actually expect will be used at the trial either to prove the case of a party or to defend allegations made by another party.[131] Under SOP 3, these documents must be discovered as of right.[132]

This more comprehensive approach to the restriction of discovery is illustrated in SOP 3, which identifies a second category of documents for ‘specific disclosure’. These documents may only be obtained, by way of discovery, upon an application being made to an associate judge, who may order discovery subject to terms relating to matters such as the classes of documents that are additionally to be discovered and which party will pay the costs of any necessary search.[133] The TEC List case Page Steel Fabrications Pty Ltd v Thiess Pty Ltd provides a useful illustration of the application of this provision. In the directions hearing,[134] Vickery J ordered that discovery be conducted in accordance with the standard discovery protocol from SOP 3, which, in para 3.3, limits discovery to:

(a) documents on which the party relies to prove its case; and

(b) documents that are adverse to the party’s own case … ; and

(c) documents that support another party’s case … ; and

(d) documents that are adverse to another party’s case …

The order in Page Steel Fabrications demonstrates that the court is willing to make use of the new powers to limit discovery to only those documents that are necessary for the fair conduct of the case. The result of narrowing the test for discovery in TEC List cases should be that the wholesale discovery of all the documents generated during a construction project is the exception rather than the norm.

It should, however, be recognised that narrowing the scope of discovery does come with its own risks. It has been suggested that it ‘may result in the loss of important information’ and ‘requires greater reliance on the integrity of the parties’ and their independent assessment of the relevance of documents to an issue in the pleadings.[135] Furthermore, the VLRC has stated that ‘[a] wide interpretation of a narrow test of direct relevance may not result in any practical difference to the scope of discovery.’[136] However, these are issues which can adequately be controlled via increased case management by a TEC List judge.

Another key discovery reform introduced by the TEC List is the discovery conference. Justice Vickery has indicated that the discovery conference was specifically created in the TEC List in response to a mining case[137] which involved a claim of $900 million and the discovery of approximately 1.8 million documents.[138] As part of the broader SOP 3, the purpose of the discovery conference is to ensure that discovery is cost effective and that only appropriate documents are discovered and the use of ADR is considered.[139] SOP 3 requires that before the resources conference is convened, parties and their legal representatives confer at a discovery conference for the purpose of:

(a) considering the issues set out in [a pre-discovery conference checklist which is annexed to SOP 3];[140]

(b) considering the use of technology in the management of documents and the conduct of proceedings including a practical and cost effective discovery plan having regard to the issues in dispute and the likely number, nature and significance of the documents that might be discoverable in relation to them; [and]

(c) reaching an agreement about the use of protocols … for the electronic exchange of documents and other issues relating to efficient document management in the proceeding …[141]

If the parties fail to conduct a discovery conference, the court may order the parties to convene one or more discovery conferences, as necessary.[142] Although the TEC List is yet to employ the discovery conference capability, Justice Vickery has acknowledged its importance and indicated that the only reason that the facility has not been used to date is that there has not yet been a case which has warranted its use.[143] It is clear that in instances where practitioners seek to use discovery in a protracted fashion, the discovery conference will serve as a useful weapon in the court’s armoury for managing discovery.

The TEC List Standard Operating Procedure No 4 of 2009 — Production by Electronic Transfer of Documents (‘SOP 4’) stipulates that all electronic project documents of a party relating to the subject matter of the dispute must be provided electronically in a form which is able to be searched by the receiving party’s legal representatives.[144] In what is believed to be a world first, SOP 4 mandates the use of search engines in the discovery process.[145] This is intended to avoid the need for parties ‘to painstakingly search out all documents which may be relevant’.[146]

Privileged documents are excluded from this process pursuant to a prescribed procedure.[147] The process ‘may only be employed with the mutual consent of the parties.’[148] According to the Supreme Court’s annual report:

The principal advantages … are: (i) saving the costs of the initial search by the providing party; (ii) saving costs of review by the receiving party by utilisation of ‘smart’ search technology; and (iii) minimisation or elimination of discovery issues on questions of relevance.[149]

This new procedure did not take effect until September 2011, and thus remained untested at the time of writing. There remains, therefore, some doubt as to how effective these changes to discovery will be. What is clear though is that giving judges power to proactively manage discovery will have little impact if judges are reluctant to exercise such power.

Justice Vickery has been instrumental in the introduction and development of a new, electronic case management system (‘RedCrest’), which is initially being launched in the TEC List on a pilot basis with a view to expanding it to the rest of the Court.[150] In the TEC List, all documents must be filed with the Court using RedCrest, unless the Court orders otherwise.[151] The system may be accessed online ‘24/7’ by solicitors and counsel for filing, viewing and using all documents in a proceeding.[152] RedCrest offers a comprehensive ‘one-stop-shop case management system for proceedings in the TEC List’, presented in a simple, workable and secure format to assist in the management of a case from start to finish, and ‘will significantly enhance communications between the Court and those participating in litigation.’[153]

As noted above, construction litigation is renowned for its heavy reliance on expert evidence. The TEC List innovations are geared at minimising difficulties associated with the use of experts — adversarialism and bias — by using a common expert, limiting expert evidence and introducing new methods for the presentation of expert evidence.[154]

Newman outlines a crucial difficulty with the giving of expert evidence, stating that expert witnesses are subject to adversarial pressure as much as, or perhaps even more than, lay witnesses, given that many make their living primarily from giving reports for evidence in litigation.[155] The difficulty surrounding experts in construction litigation is that the trial is conducted on an adversarial basis, and, if the old adage is to be believed that ‘he who pays the piper calls the tune’, an expert witness’s neutrality may be endangered.[156]

A difficulty highlighted by Ulbrick is that, while the rules impose a ‘duty’ on experts to provide independent and dispassionate analysis of the facts, they do not bar the admissability of evidence given in breach of this duty.[157] Instead, lack of independence or adversarial bias goes only to the probative value of the evidence.[158]

A further problem with expert evidence concerns how an expert’s opinion should be expressed in any report. Ulbrick asserts that ‘construction lawyers must interact with experts to ensure that the reports produced are “user friendly” in respect of both the opinions expressed and to determine whether those opinions meet the requirements for admissibility.’[159] This presents ‘an obvious ethical dilemma … between the lawyer’s ever-competing duties to the client and court.’[160] While a lawyer’s involvement is supposed to be focused on the admissibility requirements and not the opinions expressed, the distinction can become blurred.[161] Consequently, lawyers’ involvement in the preparation of expert reports and the preparation of witnesses for oral testimony has been described as ‘one of the “dark secrets” of the legal profession.’[162]

The TEC List addresses these neutrality concerns, as well as other concerns about the cost and delay associated with expert evidence, through a range of measures which are discussed below.

The resources conference is one way that the TEC List seeks to reduce expert costs, address neutrality concerns and minimise the use of multiple experts, by requiring parties to consider

[w]hether any and if so what experts have been or are expected to be retained for the purposes of the proceeding, the field or fields [of] expertise to be addressed by expert evidence and whether a common expert might be jointly retained …[163]

These reforms are based on the TCC in the UK, where the Court may direct that evidence be given by a single joint expert and select that expert if the parties cannot agree who it should be.[164] Tony Bingham cautions against the use of a common expert, identifying four problems. First, cases using a single expert are ‘umpteen times more expensive’ than cases with experts who work with the parties to ‘get to the bottom of the technicalities’ and create a ‘flow of information, dialogue, frequent phone calls and meetings.’[165] It is during this time that experts may convince clients that their case is weak.[166] Second, where each party has an expert, during the course of proceedings experts will often ‘reach joint agreements and cut out huge parts of a case, saving masses of cash.’[167] Third, while ‘of course’ single joint experts will create a less adversarial culture and achieve earlier settlements where their findings are unable to be challenged, limiting experts means that advocates are spending money not to engage their own expert, but rather to engage a ‘shadow’ expert to assist with ‘testing the so-called single expert’.[168]

Despite these criticisms of the use of a single expert, the Emerging Findings report of the Lord Chancellor’s Department found that in the UK, ‘[t]he use of single joint experts appears to have worked well. It is likely that their use has contributed to a less adversarial culture [and] earlier settlement and may have cut costs.’[169] According to the report — which did not differentiate between construction and non-construction cases — single joint expert witnesses were used in 41 per cent of cases where expert evidence was given.[170]

Notwithstanding Bingham’s concerns, it is appropriate to retain a common expert where:

1 ‘the sums at stake in litigation are small in relation to the costs likely to be incurred’;2 ‘the expertise consists of personal judgment or ‘feel’ derived from experience (such as valuation evidence)’;

3 ‘the evidence which the court needs to have explained is relatively uncontroversial’; or

4 ‘the issue is relatively peripheral.’[171]

However, TEC List judges should be very conscious not to require a single expert in cases where the size and complexity of the dispute is such that the use of a single expert could undercut adversarial standards and increase costs because parties proceed to litigation without truly knowing the merits of their case.[172]

Another TEC List reform relating to experts is that judges may now place limitations on a party presenting their case,[173] including limits on the time allowed for examination, cross-examination and/or re-examination,[174] the number of witnesses (including expert witnesses) that a party may call,[175] and the time allowed for oral submissions.[176] The power to place such limits responds to concerns about the Court’s inability to limit the number of expert witnesses.[177]

Placing restrictions on the time that parties are permitted to present expert evidence and make oral submissions is ‘a practice that has long been adopted in international arbitration’.[178] These reforms appear sensible where ‘[e]xperience shows that cases are decided on one or two points and limited length trials force the parties to determine what those points are.’[179] However, whether or not TEC List judges will proactively use this innovative power to reduce costs and increase efficiency in construction litigation is yet to be seen.

A further TEC List reform is provision for a judge to, with the consent of the parties, order that experts ‘meet in conclave and report on the points of agreement and disagreement’.[180]

Expert conclaves seek to overcome the adversarial tendencies which create excessive costs and time delay when played out through experts’ evidence, while still giving the parties the opportunity to select the experts of their choice. The use of such meetings resembles the TCC’s practice, whereby the Court may direct that experts meet to identify the issues in the proceedings and, where possible, reach agreement.[181] Justice Dyson noted that ‘the long-standing requirement in the TCC that experts of like disciplines meet to narrow and agree issues has spared this court some of the worst excesses identified by Lord Woolf.’[182]

Expert conclaves are often used in VCAT. Where VCAT considers it suitable, it can order a ‘chaired’ conclave of experts,[183] which is ‘conducted, in the absence of the parties and their lawyers, by an experienced building consultant mediator or a member.’[184] The experts prepare a joint report, which identifies the issues on which they have agreed and disagreed and forms the basis of the agenda for the hearing of concurrent evidence.[185] The report emanating from the expert conclave often serves as a catalyst to the parties engaging in informed settlement negotiations.[186] Thus, expert conclaves can serve dual purposes, namely, to encourage constructive settlement negotiations between the parties and to make the conduct of the trial more efficient if settlement negotiations fail.

While genuinely polarised expert opinions — arising from, for example, different life experiences or different assumptions — can impede the effectiveness of expert conclaves,[187] ultimately disagreements can be largely resolved by open debate under the supervision of an experienced judge with relevant expertise.[188]

If the TEC List is able to follow VCAT’s lead and have a judicial officer chair expert conclaves, as the reforms permit, then the result is likely to be significant time and cost savings for both the parties and the court. The reasons why the VCAT expert conclaves may be so effective is that they facilitate the parties having informed settlement negotiations at a compulsory conference convened shortly after the conclave. Compulsory conferences, discussed further below, are a form of ADR that is facilitated by a VCAT member.

The final TEC List reform relating to experts is the provision allowing for expert evidence to be given concurrently, also known as ‘hot tubbing’. According to Andrew Stephenson and Andrew Barraclough, expert evidence is traditionally heard amongst the factual evidence presented by the party calling the expert, which may mean that

the opposing expert witness may not be heard for weeks or months (in a complex matter) after the first expert evidence is heard. Hot-tubbing separates the expert and factual evidence. The factual evidence is heard first in a conventional way. Then each discipline of expert evidence is heard together with both sets of experts giving presentations back to back.[189]

The result is a much more logical sequencing of evidence. This practice appears to have been developed initially under Justice Lockhart when he sat as president of the Trade Practices Tribunal (now the Australian Competition Tribunal).[190] The potential advantages of using concurrent evidence were illustrated in Coonawarra Penola Wine Industry Association Inc v Geographical Indications Committee,[191] where a hearing expected to last six months only took five weeks.[192]

Hot tubbing is permitted in VCAT;[193] indeed, ‘VCAT procedures make it quite explicit that the parties should expect the experts to give evidence concurrently and give a description of the mechanics of that procedure.’[194] The process resembles more of a discussion where experts answer questions from the VCAT members, the lawyers and their professional colleagues.[195] Allowing experts to communicate directly, and phrase questions in their own terminology, helps to ‘crystallise the areas in dispute’.[196] However, Knight has expressed caution about concurrent evidence, noting that

[o]ne of the challenges for those involved in hot-tubbing that should be guarded against is the potential for confusion of the roles of experts in court proceedings. A party’s case could be damaged if, for example, an expert were to cross the line between being an independent expert and an advocate. This is something all parties should remain conscious of and endeavour to avoid at all costs.[197]

While this risk may be a potential pitfall of hot tubbing, it can be minimised by appropriate preparation of experts prior to the hearing. Overall, the benefits of concurrent expert evidence, including savings in time and costs, make this option for giving evidence in TEC List cases most attractive.[198]

A further notable reform introduced into the TEC List is giving judges the power to require parties to prepare a Statement of Issues. If practitioners have drafted pleadings to be, for example, ‘as comprehensive and general as possible so as to provide a basis for contending that anything is relevant’[199] and have not defined the real issues, a TEC List judge can give ‘[d]irections that some or all of the issues raised in the pleadings be reduced to a Statement of Issues which may be settled by the Judge in consultation with the parties’.[200] Further directions may also be given ‘that the proceeding or part of the proceeding be conducted … in accordance with and by reference to the Statement of Issues’.[201]

A Statement of Issues is a document setting out, in summary form, the factual and legal issues in dispute, and the party’s position and interests in the dispute. Vickery J has put to rest concerns that judges will not take up this new innovation by recently ordering parties to consult with each other for the purpose of settling a common list of issues of fact and law to be determined by the court.[202]

The TEC List Statement of Issues in some ways resembles the Scott Schedules used by the TCC.[203] Scott Schedules were first used by G A Scott, a former official referee[204] involved in building cases in the UK.[205] A Scott Schedule is a table in which the plaintiff itemises its allegations (for example, each defect or variation), and the defendant then adds its position with respect to each item.[206] Parties may not make non-specific allegations or simply “not admit” or “deny” their opponent’s allegations.’[207] Scott Schedules are the antithesis of pleadings, which are often extremely voluminous and unnecessarily complex and require an inordinate amount of time just to decipher what the issues actually are. In the TCC, a Scott Schedule is often a complete substitute for pleadings. Furthermore, a TCC judge can give directions as to what column headings they consider to be relevant, so as to reflect the information and issues the Court wants clarified. The use of Scott Schedules is not unknown in Australia: in VCAT, ordering the preparation of Scott Schedules is a part of the standard directions.[208] The following is an example of the headings used by VCAT in a Scott Schedule in a case involving experts for both parties:[209]

|

Item No

|

Brief Description of item

|

Owners’ Expert’s

Comments

|

Agreed

Y/N

|

Builder’s Expert’s

Comments

|

Owners’ Estimate $

|

Builder’s Estimate $

|

Tribunal’s comments

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A slightly different model is provided by Dorter and Sharkey in their seminal work. The example given for a claim is:[210]

|

Item No

|

Item

|

Reason

Claimed

|

$ Claimed

|

Reasons disputing

|

$ Allowed

|

Reply Decision

|

|

1

|

variations

|

extras necessary

|

345,000

|

(a) no Architect’s Instructions

(b) not Variations

|

Nil

|

(a) notified Architect

(b) procedures waived

|

|

2

|

final payment

|

Defects Liability Period expired

|

8,000,000

|

no final certificate

|

Nil

|

waiver

|

|

3

|

interest

|

|

|

|

Nil

|

|

The example given for a counterclaim is:

|

Item No

|

Item

|

Reason claimed

|

$

Claimed

|

Reasons disputing

|

$ Allowed

|

Reply Decision

|

|

1

|

rectification

|

|

1,400,000

|

(a) no defects

(b) no loss or damage

|

Nil

|

|

|

2

|

liquidated damages

|

|

4,000,000

|

(a) penalty

(b) no loss or damage

|

Nil

|

|

The above examples illustrate that there is no standard form of Scott Schedule. Rather, they can be crafted to suit whatever issues are in dispute.

The TEC’s Statement of Issues provides an avenue for summarising pleadings, but there is still a requirement that general pleadings must first be filed and served before the court can order the preparation of a Statement. This practice leads to double handling of the information, with associated costs.

While the introduction of a Statement of Issues may be useful for the consolidation of issues in illusive pleadings, the authors suggest that Scott Schedules are a better alternative. As Richard Manly SC notes, ‘Scott Schedules in appropriate cases [are] the perfect tool to facilitate [the just, efficient and timely resolution of cases] and thus the analysis of much data in a cost-effective, time-saving and convenient manner.’[211] Furthermore, they have a long and successful track record, while Statements of Issues are new and untested. Scott Schedules can be a complete substitute for traditional pleadings in appropriate cases, and provide an efficient means of summarising complex information, including multiple expert opinions, as illustrated in the above example. The preparation of a Scott Schedule may also ‘increase the possibility of the parties reaching a settlement on at least some portion of the issues in dispute [and] avoiding confusion at the hearing.’[212] While the introduction of a Statement of Issues has the potential to improve construction litigation in the Victorian Supreme Court, Scott Schedules continue to represent best practice in terms of narrowing issues and forcing parties to clearly set out their positions on each and every item in dispute.

International arbitrations have long used ‘chess clock’ hearings, where fixed time limits are imposed on the parties for the hearing. The United Nations Commission on International Trade Law states that:

Such planning of time, provided it is realistic, fair and subject to judiciously firm control by the arbitral tribunal, will make it easier for the parties to plan the presentation of the various items of evidence and arguments, reduce the likelihood of running out of time towards the end of the hearings and avoid that one party would unfairly use up a disproportionate amount of time.[213]

The new TEC Rules specifically give the Court the power to conduct limited time, chess clock hearings.[214] Imposing time limits on advocates ‘allows for a more accurate and earlier estimate of the time that will be needed for the hearing’ and ‘forces counsel to focus their arguments and examinations of witnesses on core disputed issues.’[215]

While chess clock procedures may be effective in achieving an expeditious trial process, they may work unfairly in some cases. It has been noted that

a deep pocketed litigant could file twice the number of lay statements and expert reports as that filed by the opposite party who may not be as financially well-off. In those circumstances, it would potentially be unfair to allocate the same amount of time to both parties, for the less well-heeled party might not be expected to deal adequately in cross examination with the evidence adduced by the deep pocketed litigant.[216]

In light of the perceived deficiencies, TEC List judges must be sure not to derogate from the duty to afford procedural fairness to the parties.[217] However, if the TEC List can effectively elevate the use of chess clock procedures into mainstream construction litigation, then the spectre of long openings and cross-examination spanning days, or even weeks, may evaporate.

In an attempt to increase cost-effective litigation, the TEC List reforms provide that:

Without limiting the power and discretion of the Court as to costs, the Judge in charge of the List or the TEC trial Judge may, if the occasion warrants, make orders that costs be awarded on an issues basis, or that the costs of an unsuccessful issue, of unnecessary discovery, of the unnecessary inclusion of documents in the court book or the unnecessary use of resources may not be allowed to the successful party or that these costs be awarded against a successful party.[218]

As the TEC List now has the Resources Conference Report, which details what limitations were agreed upon, it should be a relatively straightforward matter for a judge to determine whether a party has engaged in conduct that warrants cost sanctions. This express power to award costs with respect to specific issues or conduct, based on how a party has managed the litigation, is designed to encourage parties to comply with agreements governing the resources to be expended and the manner in which proceedings will be conducted.[219] The reasoning behind the greater cost sanctions is that ‘[l]itigants would be less likely to drive up their opponents’ costs if they ran a significant risk of bearing these costs themselves.’[220]

In the TCC, greater cost penalties have been described as ‘a central plank of the Woolf approach to civil litigation.’[221] The TCC’s stance is that ‘the court should not endorse disproportionate or unreasonable costs.’[222] In line with this stance, ‘[a] party who conducts litigation in a protracted and unreasonable manner’ may, despite winning the case, be ordered to pay costs.[223]

The VLRC has not wholeheartedly endorsed the more detailed cost provisions adopted by the TEC List, voicing the opinion that the Court already has extensive powers under statutory provisions, court rules, and/or pursuant to its general jurisdiction to impose sanctions, including costs orders.[224] It may be that TEC List judges do not need more explicit costs powers, but rather an increased willingness to use costs orders as a means of managing litigation.

The TEC List reforms represent a step in the right direction when it comes to improving the time-consuming and costly practices that have become commonplace in construction litigation in Victoria. However, there are still a number of areas where further reform is warranted in order to achieve best practice, including the following three specific reforms that would significantly improve the conduct of construction litigation in the TEC and enable the Victorian Supreme Court to attain world’s best practice in this area. Cultural change is also needed to assist with this improvement.

Civil justice reform, including construction litigation reform in Victoria, has focused on civil procedure rules.[225] However, equally important to the administration of civil justice is ‘the institutional architecture … and apparatus for processing and adjudicating civil claims and disputes.’[226] While the rules relating to construction litigation have been reformed, the ultimate forum for hearing disputes is still unsatisfactory. Under the Victorian system, the judge responsible for managing the TEC List may, or may not, ultimately preside over the trial. This is in stark contrast to the system in the Federal Court, where the judge who oversees all the interlocutory steps also presides over the trial.

The fact that any Supreme Court judge may be allocated a construction case leaves litigants in a precarious situation, with the very real possibility that a complex construction case may be tried by a judge with little, or no, knowledge of construction law or practices. In 2005, Justice Habersberger, who was at the time the judge in charge of the Building Cases List in the Victorian Supreme Court, evaluated the idea of introducing a docket system at an early stage in proceedings.[227] The idea was that the judge in charge of the Building Cases List would, at his or her discretion, assign a case to a judge with expertise in construction disputes, who would hear all interlocutory issues and preside over the trial.[228] Justice Habersberger recognised the advantages of having the judge who manages a case also hear it, but ultimately concluded that such a system would not work for longer cases, stating that

it just does not seem practical to introduce this system into the Supreme Court at this time because of the sheer volume of cases. Given the competing demands for Judges to hear cases, I doubt that the Listing Master could facilitate Judges to fix their allocated cases any earlier … Allocation to the trial Judge has also been sought in a number of matters recently referred to the Listing Master, but the problem is that it is very difficult for the Listing Master to allocate a case to a particular Judge so far into the future.[229]

Notwithstanding the reservations of Justice Habersberger, the authors maintain that a docket system which provides for specialised construction cases is fundamental. A complex construction case requires that the judge presiding over the trial understand the intricacies, terminologies and concepts involved in construction projects. The importance of having expert judges hearing construction disputes was evident in the appointment of Sir Vivian Ramsey[230] to the English High Court for the express purpose of sitting in the TCC.[231] It was observed that

[i]n the past, on the relatively rare occasions when such practitioners were appointed to the High Court bench, they were appointed despite being construction specialists and not because of it and they were appointed in the expectation that they would sit in a completely different jurisdiction.[232]

A specialist court such as the TCC, which only hears construction and technical cases, is superior to the one currently in operation in the TEC List. While it must be borne in mind that Victoria has a much smaller economy and construction industry than the UK, it would still be ‘desirable for complex building disputes [to] be managed and tried before [judges] with some experience and expertise in construction law because this adds considerably to the efficiency and expedition of the trial’ as a whole.[233] The Victorian Supreme Court does not need to change the whole court structure in order to achieve this result. A docket system, such as that which already exists in Australia in the Federal Court, would also serve as a satisfactory model for ensuring that construction cases are heard by judges with relevant specialist experience.[234] After widespread consultation with practitioners and members of the judiciary, the Australian Law Reform Commission reported that the Federal Court’s individual docket system had attracted ‘unanimous positive feedback’.[235] However, a docket system is unlikely to be viable within the TEC List unless there are more judges with construction law expertise assigned to that List.

At VCAT, parties to a proceeding may also be required to attend one or more compulsory conferences before a member before the proceeding is heard.[236] Members appointed to VCAT are ‘considered to be expert, which assists in the adjudication of technically difficult disputes’, and they can range from ‘doctors, engineers, scientists, town planners and architects’ to ‘sessional members, who are on call at all times to hear cases in their specialist field.’[237] This specific knowledge may assist the parties to resolve their disputes ‘through informal discussions based on accepted … methodologies.’[238]

Compulsory conferences are designed ‘to identify and clarify the nature of the issues in dispute in the proceeding’,[239] ‘to promote a settlement of the proceeding’,[240] ‘to identify the questions of fact and law to be decided by the Tribunal’,[241] and ‘to allow directions to be given concerning the conduct of the proceeding’[242] in the event that settlement is not achieved.

Compulsory conferences ‘are akin to evaluative mediation’.[243] As the VCAT members who facilitate compulsory conferences are experts in the disputed area, the real issues are often readily identified, which assists resolution of them at an early stage.[244] Compulsory conferences may help to settle disputes well before the actual hearing takes place. In fact, the most recent data available reveals that more than 93 per cent of VCAT claims that exceed $10 000 were resolved through compulsory conferences.[245] The authors suggest that compulsory conferences would greatly enhance the new TEC List expert conclaves procedures, and should be considered when the TEC List practices are next reviewed. Alternatively, they could be implemented as an additional consideration during the initial resources conference.

While the TEC List reforms mirror many of the practices of the TCC, there is one aspect which has not been embraced. The TCC has developed pre-action protocols (‘PAPs’) to encourage the parties to fully explore settlement prior to commencing proceedings — in other words, to make litigation a last resort rather than a first.[246] Unfortunately, PAPs do not specifically feature anywhere in the TEC List reforms. The authors of ‘Construction Litigation: Can We Do It Better?’ highlighted the important role that PAPs play in enhancing settlement prospects.[247] Michael Legg and Dorne Boniface concurred with this conclusion more recently, stating that ‘[p]re-action protocols have attracted interest in Australia as a way to promote access to justice, efficiency, proportionality, the utilisation of alternative dispute resolution and cultural change.’[248]

Even where settlement is not achieved, PAPs can assist in the efficient conduct of litigation through early issue identification and greater sharing of relevant information. While parties seeking to commence litigation in the Victorian Supreme Court are ‘expected to have engaged in serious settlement discussions before the commencement of … [proceedings]’,[249] there is no elaboration as to specifically what is expected of the parties.

The TEC List does not have any specific pre-action procedures. The Victorian government, in the wider context of reform of civil litigation, did enact the Civil Procedure Act 2010 (Vic), which originally required parties in a civil dispute to comply with certain pre-litigation requirements, such as taking reasonable steps to resolve the dispute by agreement.[250] However, with a change of government in Victoria in late 2010, these pre-litigation requirements were repealed.[251]

The removal of any pre-litigation requirements effectively eradicated a crucial limb of the Civil Procedure Act. The result is that parties to construction disputes are left with only the very weak and vague TEC List direction that they ‘will be expected to have engaged in serious settlement discussions before the commencement of the proceeding’.[252]

It is clear that the TEC List has modelled many of its innovations on the TCC, with the aim of achieving the same improvements to the conduct of construction litigation. However, the underlying philosophy of the TCC — derived from Lord Woolf’s goal of promoting settlement of a dispute before litigation is commenced or as soon as possible thereafter[253] — does not appear to have been at the forefront of the TEC List reforms. This is regrettable, since pre-trial procedures can reduce the strain on court resources and emphasise the importance of parties working together towards an effective resolution of their dispute.

Justice Byrne has warned that ‘procedural reform without cultural change is not likely to achieve very much’.[254] Edson R Sunderland expressed similar concerns in the 1920s when he noted that

[h]abits of thought determine not only what facts we see but the light in which we see them. In the case of the legal profession the habitual use of a fixed procedure has made the majority of … lawyers utterly incapable of appreciating how absurd are the technicalities which cripple its usefulness.[255]

It is a concern that this sentiment is as relevant today as it was when first published approximately 90 years ago, and worrisome for the future of TEC List litigation. While the objective of the TEC List requires a more cooperative and responsible approach to resolving disputes, the inherent nature of the adversarial system is at odds with this purpose.

The legal mind must be expanded and opened to interdisciplinary problem-solving methods if construction litigation in Victoria is to improve.[256] Kathy Douglas argues that lawyers gain a ‘standard philosophical map’ through their legal education, and that this tends to privilege the role of litigation in dispute resolution.[257] Therefore, reform to the legal profession and legal education should be considered in tandem with procedural reforms. Lawyers must recognise the importance of striking a more appropriate balance between their obligation to their clients and their role in facilitating the resolution of disputes by means other than trials.[258]

A more basic, but certainly no less effective, approach would be, as Justice Byrne has suggested, to simply say: ‘We, that is the parties, have a problem. How best can we, that is the lawyers, resolve this question?’[259] It is this sort of attitude that is required if construction litigation in the Victorian Supreme Court is ever going to reach world’s best practice.