University of New England Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New England Law Journal |

|

COLLABORATIVE SUPERVISION OF LEGAL DOCTORAL THESES THROUGH E-LEARNING[1]

ABSTRACT

Doctoral supervision does not have to be limited to face-to-face master apprentice or co-supervisory models. Doctoral supervision may instead be implemented through a collaborative supervision model based on an electronic community of practice involving distance education students. Collaborative network approaches to supervision may in fact offer distinct advantages over traditional supervisory processes. This article proposes a model and exemplar of collaborative supervision implemented through an electronic community of practice.

Doctoral supervision of law candidates traditionally has involved either a 1:1 master apprentice model or co-supervisory model based on face-to-face meetings. This article challenges this paradigm by examining collaborative supervision models based on an electronic community of practice involving students from distant locations who may never physically meet each other or their supervisor in person. The creation and implementation of an electronic community based on an action research methodology is used as an exemplar.

Law faculties like many of their counterparts that Neumann described as a mode 1 form of knowledge production, engage in ‘the traditional form of university-based research, determined by disciplinary dynamics and undertaken by an academic elite’.[2] In this environment the student is often seen as a lesser in the supervision relationship. There is a clear power imbalance in favour of supervisors. There is limited interaction between students. Doctoral students are usually dealt with individually in the context of 1 to 1 meetings[3] except for university level workshops or occasional seminars on postgraduate supervision.[4]

The common supervision approach in law is the 1:1 supervision model based on the master apprentice relationship. Knight and Zuber-Skerritt in ‘advocating inclusion of course work to supplement supervision, analysed the assumptions underlying the traditional 1:1 relationship’.[5] The assumptions include:

| • | ‘Supervisors are competent to advise and teach the student the necessary research skills; and |

| • | Students have already acquired the necessary skills from their undergraduate courses and that these skills translated to postgraduate research.’[6] |

These assumptions are flawed. Knight and Zuber-Skerritt[7] suggest these assumptions were unfounded and not applicable to all supervisors and research students.

Knight & Zuber-Skerritt[8] further suggest that the supervisor should be able to impart research and writing skills to students. An accepted view amongst supervisors of law PhDs, including myself, is that while recently graduated students may have legal research skills they lack skills in critical and analytical thinking, knowledge of alternative research methodologies, project design management and evaluation, self-management, and time management, in addition to a lack of writing skills.

The 1:1 master apprenticeship approach has been extended to co-supervisory approaches. The first supervisor (Principal supervisor) generally takes a major responsibility for the candidate.[9] Under both approaches[10] the prevailing legal supervision paradigm would suggest that a supervisor is not a nanny and that supervision is largely a ‘hands off affair’. Interviews with experienced supervisors suggest that students often develop their own topics and research plans with minimal assistance from their supervisor.

While co-supervisory approaches have emerged to back up and train junior supervisors they have largely failed in improving supervision in the QUT Faculty of Law despite the law school policy encouraging co-supervision. An interview with a very experienced professor revealed that few trainee supervisors attended meetings and some of the problems identified by Aspland et al,[11] based on the work of Phillips and Pugh,[12] arose, including: conflicting advice, students playing one supervisor off

against the other, etc. In many cases the actual practice still maintains the traditional rather than co-supervisory approach.

Where co-supervisory approaches have been implemented they focus on the introduction of a second academic supervisor rather than taking advantage of the input of further PhD students or a combination of both. The construction of co-supervisory approaches should be broadened to include situations of a single principal supervisor (with or without a co-supervisor) supervising multiple students in a group situation — a collaborative network. A collaborative network approach to supervision offers opportunities for empowerment as self-growth. Smith[13] has identified several positive factors for students involved with collaborative supervision including:

| • | ‘Changes in self-knowledge |

| • | Increases in self esteem |

| • | Strengthening of personal confidence |

| • | Growing sense of determination and assertiveness |

| • | The acquisition of specific social/work skills’[14] |

Aspland et al,[15] citing Bourner and Hughes,[16] identify the benefits of co-supervision as offering a second opinion, greater collective experience, and insurance against departure of a supervisor. It can be extrapolated that supervision through a collaborative network may enhance the first two of the three benefits for students identified by Bourner and Hughes.[17] This approach purposely blurs the distinction between the 1:1 master apprentice, co-supervision, and group supervision.

The collaborative network approach may be further extended to engage students in the supervision of peers. Pearson and Ford[18] suggest such an approach, ‘can create a peer network and peer critical support which can enable students within the group to play the role of apprentice to each other or take over the role of supervisor in relation to other students, as the needs of the individuals in the group required’.[19] There is no doubt traditional approaches to supervision can be successfully supplemented by reciprocal peer support.[20]

The rationales for considering such an approach were summarised by Conrad et al[21] as:

| • | ‘Funding pressures suggest investigating methods of reducing the costs of traditional supervision |

| • | Increases in the numbers of postgraduate students and a concomitant decrease in the number of qualified supervisors |

| • | Increasing complexity and shortening ‘half-life’ of modern knowledge suggest the need for greater supervision support |

| • | Candidates sense of social and intellectual isolation’[22] |

The paradigm of law student supervision has largely overlooked the collaborative network approach to supervision and the synergy evident with students facing similar issues, and the support network that this may base.

Recent national policies[23] have significantly impacted on university research. In response, QUT’s Innovation Plan 2003–2007[24] calls for:

| • | ‘Concentration of resources in areas of strength |

| • | Increased PhD enrolments, maximising completions in minimum time |

| • | Proactive collaboration with industry, public sector, end-user and philanthropic investors in research partnerships |

| • | Dissemination of the outcomes of research, including through publication’ |

The QUT Law Faculty has responded by a draft research policy[25] focused on:

| • | ‘Encouraging publication of research scholarship |

| • | Recognition and encouragement of teams of researchers pursuing research programs as a cornerstone for concentrating areas of strength |

| • | Funding PhD scholarships to attract high quality students |

| • | Facilitating the movement of undergraduates into research |

| • | Clarifying responsibilities and requirements for supervision by detailed supervisor duty statements for different research degrees.’ |

Great emphasis is now placed on maximum completion in minimum time. Academic attention is focusing on dissertation management as a means of meeting the policy agenda. The challenge will be to change academic mindsets to encourage the development of new techniques that maintain and build student responsibility without overly prescriptive management regimes. The traditional ‘hands off’ approach to supervision in law may no longer be appropriate.

One approach to dissertation management is to embed the process within a structured framework using Internet based technology. Project management software widely used in business may be usefully implemented in the supervision process. This article describes how this may be done as part of a collaborative supervision network established on the Internet — a virtual community.

Conrad, Perry and Zuber-Skerritt[26] described a structure for supervision involving students in their own and each other’s supervision. This is the approach adopted in this research project. In Table 1 reproduced below they depict a number of supervision permutations and combinations having one common characteristic:

they represent groups of students who meet in order to share access to faculty supervision and other resources and/or to assist each other in completing their postgraduate research.

Table 1 Supervisory group variables and associated

continua of differences[27]

|

Variable

|

Poles of continuum of differences

|

|

|

Genesis

|

Faculty-initiated*

|

Student initiated

|

|

Structure

|

Formal*

|

Informal

|

|

Focus

|

Task-driven*

|

Psychologically driven

|

|

Timing

|

Regular*

|

Irregular

|

|

Membership

|

Frequent large

|

Infrequent small*

|

|

Supervision

|

Consistent Single faculty* Supervisor

|

Fluid Many faculty supervisors

|

|

Discipline affiliation

|

Related*

|

Unrelated

|

|

Research projects of group members

|

Related content Related methodology

|

Unrelated content* Unrelated methodology*

|

|

Institutional affiliation

|

Intra-institutional*

|

Inter-institutional

Cross-institutional

|

Indicated with an asterisk in Table 1 is the approach adopted in this article for developing a collaborative network approach to supervision. Further variables may be added to the list in Table 1 including student enrolment status (part-time/full-time), gender, and age.

The issue is whether in the current climate of graduating maximum PhDs in minimum time it is possible to expand the notion of supervision beyond the traditional 1:1 master apprentice model and the co-supervision model to consider group supervision using a virtual community of practice.

An extension of the Conrad et al[28] approach is for a supervisor and all PhD students under his or her supervision to engage in collaborative network supervision, supported by E-learning strategies based on carefully designed website. I refer to this approach as a ‘Supervision cell’ which is depicted in Figure 1. This article describes how such a supervision cell in the form of an electronic community of practice was developed and implemented with three doctoral candidates in law.

External resources

Website

Student 2

Student 1

Supervisor

Figure 1 Supervision cell

In Figure 1, the supervisor and each student are equal participants in the process. Students may interact with each other through the website and with the supervisor directly.[29] It would be inappropriate for students to communicate directly with each other leaving the supervisor out of the loop. The supervisor has an ethical responsibility to supervise each student in the supervision cell. This ethical responsibility is enshrined in law school policy on postgraduate supervision, which includes, but is not limited to:

| • | Consultations as necessary (normally initiated by the student) to discuss progress of work, generally not less than monthly. |

| • | Read and return any submitted drafts or other work with constructive criticism with a month or less as appropriate. |

| • | Monitor carefully the student’s performance relative to the standard required for the degree and ensure that the student is promptly made aware of inadequate progress by specifying any problems and suggesting and discussing ways of addressing them. Notes should be kept of such discussions and actions taken. |

The website directly links students and the supervisor to external resources. The website provides the scaffolding for creating a collegial network amongst the supervised students. Collegiality is an essential feature of all good supervisor relationships.[30] Each student is an equal in the process of supervision — there is a power balance in and amongst the group.

The supervision cell challenges the accepted supervision paradigm in law. In the only significant article on supervision in law, Manderson[31] discusses the power dynamic of supervision in this context. Manderson argues supervision is a form of ‘social control: it acculturates the students into the practices of the academy; it shows, by talk and by practice, how things are done within the constraints of a discipline.’[32] He emphasises three features:

‘(i) Supervision embraces the relationship between supervisor and supervisee structured around particular roles — set in advance by convention or institutional understanding. Such structures are scaffolding which stimulates the development of the relationship in certain directions precisely by establishing specific parameters.

(ii) The relationship is developed through the process of researching and writing about a specific project. The supervisor’s role is to help students learn how to learn.

(iii) Supervision involves mutually by which both parties learn. Ultimately the student will surpass the teacher in the knowledge of the subject matter of the thesis.’[33]

The Manderson[34] approach is very restrictive of student academic freedom in line with established specific parameters set by the law paradigm. The supervision cell is more flexible in allowing all members of the cell to participate equally in the acquisition and sharing of knowledge.

The supervision cell challenges the paradigm by redefining the roles and scaffolding that defines the relationships between supervisor(s) and student. The process of learning to learn has a broader support base found amongst the members of the supervision cell. Central to the success of the supervision cell is the website — the development of which is the first stage in the action research project described later in this article.

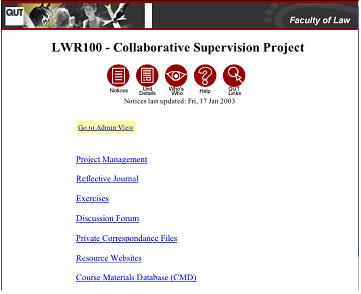

The website was based on a website developed by Terry Hutchinson for LWB412 Research and Writing Project using the Queensland University of Technology OLT shell. The website has seven main elements depicted in the screen shot of the home page — Figure 2.

The website also carries the following five standard Queensland University of Technology header links:

| • | Notices (important notices to students also e-mailed to them) |

| • | Unit Details (unit outline) |

| • | Who’s Who (who is involved in the supervision cell) |

| • | Help (basic help screens) |

| • | QUT Links (links to QUT resources) |

Each of the seven main elements will be described in turn.

Figure 2 Screen shot of homepage

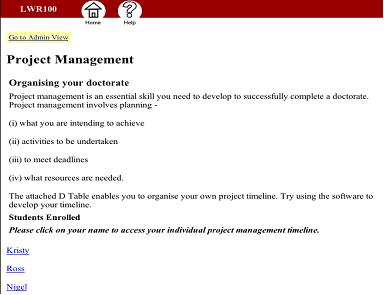

The website includes project management software and a budget plan for use by each student. Figure 3 is a screen shot of the main project management page. Each of the three students is provided with basic D tables, shown in Figure 4, that the student can modify to reflect the management issues involved with their project. Each D table covers a period of 6 months — a column for each month. Each row of the table represents an activity the student needs to plan for.

Examples might include:

| • | Dates when scholarship applications close |

| • | Report and stage submission dates |

| • | Dates of ethics meetings and reporting requirements |

| • | Dates for mail out of survey instruments |

The activities and the order in which they are tackled is a matter for the student in consultation with other members of the supervision cell. Such an approach is hinted at by Manderson who comments:

Some people need help in the process of writing: They need encouragement to organise their works, to set up and keep deadlines, to press on with the painful tasks of preparing, writing, rewriting.[35]

The supervisor has a ‘hands on’ role in both a structured, as well as intellectual way in assisting a student’s rewriting.[36] The project management aspects of the website help achieve these aims.

Each activity has a link to a page in the student’s reflective journal. A further D table is provided so that students can prepare detailed budgets for their project where necessary.[37]

Such timelines would be invaluable for projects in which the doctorate forms part of a larger collaborative research project or projects, which the supervisor has created, to attract doctoral students. An example of this may arise with APAI sponsored projects.

Figure 3 Screen shot of project management page

Figure 4 Screen shot of the timeline D table

Johnston when referring to the translation of supervision theory into practice observed:

... changes in practice are most likely to occur when there has been a carefully supported and structured series of activities which allow practitioners to reflect on their own practice, to consider particular issues of importance to their practice, and to share their experiences with a supportive group of colleagues who can challenge assumptions which underlie that practice and together develop alternative ways of approaching that practice. ... Collaboration among a group is important here to develop the level of trust which is needed for troublesome issues to be explored and for challenges to be made to what are sometimes entrenched ways of thinking about those issues.[38]

The principles identified by Johnston have been incorporated into the supervision cell through the use of reflective journals, exercises, and a discussion group. Each student has a reflective journal in which they record their progress on each activity they identify as important to their thesis. Reflections may include problems they have encountered, how those problems were resolved, how they intend to progress. Other members of the supervision cell are encouraged to read both the project management entries and reflective journals of other members of the supervision cell, with a view to making comments and suggestions.

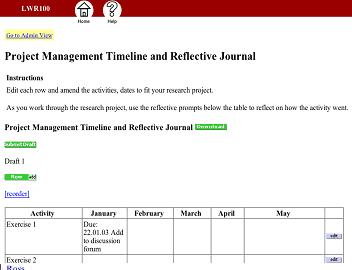

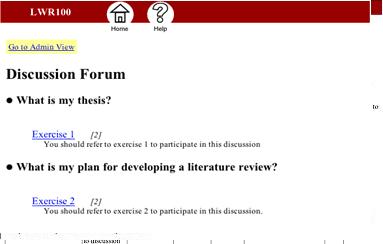

The website includes exercises, shown in Figure 5, designed to direct student attention to significant issues in their thesis development. For example the first exercise requires students to write a brief extract on what their thesis is about. This provides a useful backdrop to a discussion group exercise as well as presenting an opportunity at a later date to reflect on how the research question changes over time.[39] The second exercise requires the student to develop a plan for a literature review including discussing the purpose of the review and how it will be implemented.

Figure 5 Screen shot of exercises

Exercise 3 — PhD Blues — is designed to help students identify issues that may arise during their PhD candidature that may hinder progress. Issues may include depression, lack of motivation, financial, relationship break-ups/problems, and other emotional issues.[40] Suggested solutions may include seeking a qualified counsellor.[41]

Exercise 4 — What the examiner is looking for when examining the thesis — is designed to encourage students to write with the examiner in mind.

Exercise 5 — Publishing during candidature — discusses the pro’s and con’s of publication during candidature. The exercise helps students to select appropriate journals for their intended publications where appropriate.

Group exercises, linked with the discussion forum, have the benefit of encouraging team building, early in the group formation process.[42]

The question may be asked — are the exercises a form of coursework? Moses[43] (1987) points out: ‘Unresolved still is the issue of whether the PhD should be supervised research training where skills are the product; or whether it should be the thesis that matters, in particular the content of the thesis, as an original contribution to scholarship, an extension to the frontiers of knowledge or a useful solution to a problem in society or industry; or whether the whole exercise should be a piece of scholarship that warrants admission to the fraternity of master researchers.’[44] These approaches need not be mutually exclusive.

Pearson and Brew have identified a shift in ‘educational approach to give more emphasis to explicit skills formation, including the skills of future researchers and those in other modes of employment.’[45] In law, the traditional view prevails that no one should start a PhD unless they already have the skills necessary to complete it. This is not to say that the process does not enhance skills, or that some additional skills are acquired, particularly with respect to project management and academic writing. In some ways this observation is a reflection of the student cohort and the research process itself. Students tend to be mature in the sense that they have worked in legal offices, the public service, or business and have gained some life experience. They have mastered the art of writing clearly and concisely which holds them in good stead for academic writing.

In this context, the exercises are a form of limited coursework designed to direct student attention to vital aspects of the task with which they are engaged.

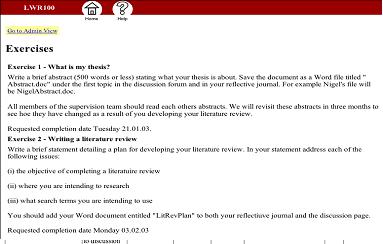

The discussion forum, depicted in Figure 6, serves two purposes. Firstly, to enable students to present and discuss their responses to the exercises. The second purpose is to enable students to post their own topics. Students may also deposit draft chapters for critique by members of the supervision cell. Such an approach helps to further build the collegial nature of the website.

Figure 6 Screen shot of discussion forum

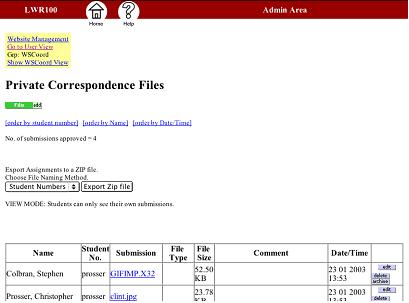

The website includes a private virtual correspondence file shown in Figure 7. The file may contain summaries of meetings between supervisor and student, chapter drafts and comments, survey instruments, SPSS data files etc. It would be also possible to keep a running bibliography including the status of interlibrary loans. The advantage of keeping private correspondence files to which only the student and supervisor may access, include:

| (i) | Secure backups; |

| (ii) | Enabling the supervisor to better keep track of the research as it develops. |

Private correspondence files still retain elements of the traditional single supervisor approach should a student desire to adopt this approach.

Figure 7 Screen shot of private correspondence files

The website includes links to useful research websites in law. One useful link is that to supervisor duty statements, which act as a ‘catalyst for discussion rather than a formal agreement’.[46] It is important that there is a clear understanding between student and supervisor as to roles and responsibilities.[47]

The website has links to useful journal articles and other materials stored as PDF files by the QUT library.

The ideas described above have been incorporated into the seven main elements of the website to create a support network and a sense of belonging to a research culture. The research culture may be further strengthened by engagement in postgraduate conferences, interdisciplinary approaches, and seminar opportunities. This will be the subject of an action plan for students later in their programme of research.

The supervision cell provides scaffolding by which the students can progress their research at their own pace with the benefit of the support of the research group. The approach clearly recognises and is flexible enough to cope with student diversity. Demands for completions in minimum time demand a much more proactive approach engaging students individually and collectively. The role of the supervisor becomes what Pearson and Brew[48] describe as a ‘“critical friend” guiding the individual “student” through the scholarly maze to the doctoral examination and graduation’.[49] Hill describes the role of a critical friend as common in action research and being intended to provide encouraging support and at the same time critical feedback.[50] The role of other members of the supervision group is less extensive.

Collins et al[51] develop the concept of ‘cognitive apprenticeship’ whereby coaching consists of observing students carrying out a task and offering hints, feedback, reminders and new tasks aimed to bring their performance closer to expert performance — see Pearson and Brew.[52] Each member of the supervision cell will observe other students interacting with the site and hopefully offer hints and feedback edging closer to expert performance. It is the role of the academic supervisor to make reminders, though peer pressure within the supervision group may also have this effect.

An extension of cognitive apprenticeship model in law would be to have a group of students at different stages of development, doing different theses (perhaps though not necessarily under the same supervisor) articulating and reflecting upon their knowledge, reasoning etc. The extension lies in both students and supervisors interacting as a collective group. A shared reflective journal could be used to record ideas observations, to reflect on progress and develop understandings. As Pearson and Brew note,

It is in critical reflection on the process of doing research, with a supervisor and informed others, that the student is most likely to clarify or discover what they really know and become able to transfer their new expertise to different problems and contexts.[53]

There is an important difference between doing the research and reflecting on the process of doing research. The later can be undertaken by a number of students regardless of whether they are at the same developmental level. These approaches are a form of what Lave and Wenger[54] describe as a community of practice. The website has been set up to create such a community amongst the three higher degree students being supervised.

Mentoring not only relates to managing candidature, career goals and intellectual development it is also relevant to supporting students with emotional and other issues. At the least, mentoring would include referring the student to appropriate counselling services. The website also includes an exercise directed to exploring this issue.

Modelling and scaffolding assist coaching. In law, modelling can be assisted by detailed editing of a small part of the student’s work, scaffolding by helping to stage the student research task — for example, preparation of a detailed research plan.

The objective is to encourage people to think and write critically — this is the true meaning of research training in the legal context, not just looking up cases and statutes which after all is a basic undergraduate skill.

The supervision cell members should be encouraged to meet each other (if only via the Internet) and discuss amongst themselves any problems they are encountering with their research. The discussion forum may be used for this purpose. Every participant has a body of knowledge they are bringing to bare. By mobilising student comments the supervision cell is more likely to be able to deal with student diversity because we are moving away from the sole expert model and into a collaborative discussion group. It will however be important to bear in mind Timothy Ferris’s comments that not all theses can benefit from management and scheduling.[55] The student must take the initiative. As Manderson correctly observes:

Guidance is very important, but there are some things a student has to do herself. Write the damn thing, for one. Students have a responsibility to do their own work, to make and keep appointments and deadlines, to define their project, to devise a research strategy and carry it out. The purpose of a supervisor is to guide students as they do all these things.[56]

The supervision cell provides scaffolding for students, the incentive of peer pressure and collegial guidance. This creates a support network and a sense of belonging to a research culture. This may mean engagement in even broader strategies such as postgraduate conferences, interdisciplinary approaches, and seminar opportunities. These approaches will be the subject of future development of the supervision cell.

The collaborative sharing of ideas amongst supervisors and students would go a long way to overcoming repetition of poor practice. Such processes may encourage more equitable power and collegial relationships between supervisor and student.

Lave and Wenger make the observation that ‘There is anecdotal evidence ... that where the circulation of knowledge among peer and near-peers is possible, it spreads exceedingly rapidly and effectively.’[57] Lave and Wenger recognise the utility in adopting a decentering strategy shifting from the ‘notion of an individual learner to the concept of legitimate peripheral participation in communities of practice.’[58] In other words, decentering the master-apprentice relationship leads to ‘an understanding that mastery resides not in the master but in the organization of the community of practice of which the master is part. While the supervisor is the “locus of authority”’[59] their role moves ‘away from teaching and onto the intricate structuring of a community’s learning resources’.[60] Such learning resources may be based on a website, such as the supervision cell.

Participation is a way of learning. Students will be absorbed into the culture of the community of practice. Lave and Wenger define a community of practice as ‘a set of relations among persons, activity, and world overtime and in relation with other tangential and overlapping communities of practice.’[61] Motivation arises in becoming a member of a community of practice.

Lave and Wenger stress the transparency amongst the community of practice and visibility in the form of extended access to information. The supervision cell achieves both transparency and visibility through open access by all members of the supervision cell.

One technique, though rare in the humanities, to achieve maximum PhD completions in minimum time is to pre-package the thesis topic. An example of this process is the APAI scheme. As Chris points out,

APAI’s are pre-packaged to the extent that quite a bit of development work has gone into the project well before a student is even appointed. My sense of it is that students really commence at stage 2 of the PhD. But this isn’t cheating! It’s collaboration.[62]

The supervision cell may support the process of pre-packaging a PhD. A draft project management and budget template could be prepared from the documentation created for the ARC Linkage APAI application. Pre-packaging may assist with the process of maximum completions in minimum time.

I have adopted the practice of asking students to audiotape all supervisor meetings, whether in person or more likely by telephone and produce a transcript retained by both student and myself. In this way, accurate records and reference points are kept — expectations are clearly documented. I found this process very useful when I prepared my thesis. The transcripts may be kept in the private correspondence files for future reference and guidance. The frequency of meetings can be reduced through the use of exercises and discussion forums. What meetings do take place may be directed at specific questions related to the student’s thesis rather than general issues that may be dealt with more efficiently when raised with the supervision group.

The supervision cell provides a constant support network whereby all can contribute to each other’s learning. Students should take control of their research early in their candidature. Students are encouraged to set agendas and plan how they are going to complete their research in a collaborative environment through the use of the project management timetable and reflective journal.

McWilliam, Singh, Taylor[63] identify dangers arising in the student supervisor relationship requiring risk management strategies, including:

| • | ‘Discourse of the lecherous professor’[64] |

| • | The harass-able student[65] |

| • | The relationship becoming too close |

| • | Misunderstandings of the nature of the relationship |

| • | The potential for ‘softmarking’ |

Within the structure of the supervision cell, the relationship between student and supervisor is no longer 1:1, but 1:several. The only exception arises in relation to private correspondence files. The nature of the relationship is plain for all members of the cell to see — transparency is a new layer of accountability, in itself a risk management strategy. This may be seen as the virtual equivalent of leaving the office door open when dealing with students. The structure also recognises that there is no single truth and that knowledge arises from varied sources. The site also links to the university policies on sexual harassment, computer usage, gender, and other equity issues.

The ethical dimensions of the supervision cell spread beyond the traditional student-supervisor relationship to embrace the responsibilities of the other students in the group. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the supervisor to monitor and manage the ethical issues arising within the supervision cell. A good example would be to ensure that appropriate recognition and citation is given for ideas generated by the supervision cell, used by an individual member of the supervision cell in their thesis.

The supervision cell is being implemented through action research. Bob Dick (2002) defines action research as:

[A] flexible spiral process which allows action (change, improvement) and research (understanding, knowledge) to be achieved at the same time. The understanding allows more informed change and at the same time is informed by that change. People affected by the change are usually involved in the action research. This allows the understanding to be widely shared and the change to be pursued with commitment.[66]

The first stage of the research was the development of the website previously described. The second stage of research involved student engagement with the website and documenting student comments. The third stage involved the resultant changes made to the website to accommodate student comments. The three stages operate as a continual cyclical event constituting the action research methodology. See Figure 8 — The action research approach.

Stage 3 Identifying required change

Stage 1 Stage 2

Website development Student comment

Figure 8 The Action Research Approach

The students who make up the supervision cell were asked for their opinions on the initial design of the website created by the supervisor. The supervision cell was implemented on a trial basis for two weeks. Initial comments of students included:

| • | What worked |

| o | The site will help with encouragement and motivation and with the process of doing the research |

| o | The private correspondence files are a good idea for backup |

| o | The management features of the site were good — keeps you on track. Frequent reference to project management and the reflective journal will keep you grounded |

| o | The reflective diaries will be useful in a generic sense to see what went wrong. We can learn from others |

| o | The exercise 1 which will be used to refer back to, will be useful. To see how things have changed |

| o | I really appreciate that a site has been set up which should give such great support. I did both my undergraduate degree and Masters by external study through QUT. During those seemingly long years I felt a bit detached from what was going on and had little contact, if any, with others studying the same subject. It will be great in this way to be connected to those in the same boat and to get your feedback along the way. Especially, if I need to be brought back on track. So in that respect the Discussion Form should be very helpful |

| o | I also really like the idea of the project management timeline. As a person who works well to deadlines and lists to things to be achieved whether it be by a day by day basis or week by week I think that the project management timeline will help greatly in keeping on the right track and not getting behind or missing important times. In that respect I also greatly appreciate the creation of exercises to do. To that end, my exercise 1 is attached. I have changed a couple of items from my original submission. After doing some more reading, I think that I would like to focus also on judicial review as an element of judicial independence and how it is being affected by tribunalisation and legislative activity to restrict judicial activity. I am working on exercise 2 and the project management timeline. My resolution is also to keep a running and up to date bibliography and list of sources. I hope that these comments are OK |

| • | What didn’t work |

| o | The methodology reflection needs a guide |

| o | A concern that too much was required in relation to meeting the needs of other members of the group — a fear that time commitments may be too large |

| • | Critical reflection |

| o | Can students add to the Course Material Database materials? Who puts it up? |

| o | Not sure about how the discussion group will work — no experience with discussion groups |

| o | I am not very computer literate |

| o | This site would really work with theses which are part of a larger project or where several people are contributing to the same project. A study group or group assignment situation |

| o | For thesis development the idea is fantastic |

Based on this initial experience with the website the following design changes were implemented:

| • | Students were permitted to submit materials to the academic supervisor administering the site to add to the Course Materials Database[67] |

| • | A guide will be developed for reflection linked to methodology, supporting reading materials |

| • | A clear statement will be written as to what amount of contribution will be sought from members of the supervision cell — a guide to balancing time and commitments |

| • | A guide will be written on how to use discussion forums, for those new to the concept |

The supervision cell can be extended in at least two further directions. Firstly, the supervision cell can be combined with other supervision cells in a honeycomb of researchers linked to research centres, shown in Figure 9. In this way a critical mass of researchers may be developed.

Secondly, further functionality may be added. For example, a handy tips section, Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ), and embedded project management screens highlighting and linking to important dates and deadlines.

Research centre

Supervision Supervision

Cells Cells

Figure 9 Honeycomb of Supervision Cells

It is important to realise that the dynamics of the supervision cell may change with new participants. Lave and Wenger[68] describe such processes as legitimate peripheral participation in communities of practice. Newcomers are motivated to become full participants in the field of mature practice through recognition of the value of participation. ‘Communities of practice have histories and development cycles, and reproduce themselves in such a way that the transformation of the newcomers to old-timers becomes remarkably integral to practice.’[69] The advantage of the structure of the website is the planning, management and documentation of this process of change. Newcomers have the benefit of a community history. The website shell has been set up in such a way as to be available for other supervisors to adopt the design. Conrad et al correctly observe, ‘if the size and scope of the area of research require it, supervisory groups may need to be supplemented by small special-interest subgroups.’[70]

Finally, the design is flexible enough to cater for student diversity in terms of different work commitments, part-time/full-time study, on campus or distance education.

Supervision need not be limited to the 1:1 master apprentice approach or co-supervision approach associated with the supervision paradigm in law. These approaches involve an interaction between supervisor(s) and the student alone, often associated with a power imbalance in favour of the supervisor(s). This article has posed, created and documented student responses to a collaborative approach to supervision in law involving multiple students and a supervisor operating within a supervision cell supported by an E-learning website. This article suggests that group supervision does have the potential for improving the PhD supervision process in law.

The supervision cell has been developed, based on an action research project whereby each member of the supervision cell contributed to the design and implementation of the supporting website.

By participating in a community of practice a new student develops an identity through changing knowledge, skill, and discourse.[71] As Lave and Wenger correctly point out,

this idea of identity/membership is strongly tied to the concept of motivation. If the person is both member of a community and agent of activity, the concept of the person closely links meaning and action in the world.[72]

The interactions of members of the supervision cell have laid the foundation for an electronic community of practice. Such an approach expands the supervision paradigm in law to include a group supervision strategy using a virtual community of practice. It is viable to supervise and support PhD students in distant locations, who may never physically meet each other, or their supervisor, in person.

∗ Professor, Head of School, School of Law, University of New Englan[d]

1 This article is in response to studying EDN628–Postgraduate Research Supervision as part of a Graduate Certificate in Higher Education at the Queensland University of Technology.

[2] R Neumann, ‘Diversity, Doctoral Education and Policy’ (2002) 21 Higher Education Research & Development 2, 168.

[3] Chris, a class participant in a conversation dated 19.01.03 describes this approach as the ‘mentor/mentee (transmission) view’.

[4] One exception to this pattern at school level emerged at the University of Queensland Law School, which on one occasion experimented with a PhD colloquium in which several PhD students presented summaries of their work to date. This is not unlike the Bath University student conference held biannually described by Geof Hill, the EDN 628 ‘Critical friend’ in an

e-mail dated 08.01.03 available from the author.

[5] T Aspland, G Hill, H Chapman, ‘Journeying Postgraduate Supervision’ (Queensland University of Technology, 2002).

[6] Ibid.

[7] O Zuber-Skerritt and N Knight, ‘Problems and Methods in Research – a Course for the Beginning Researcher in the Social Sciences’ in L Conrad,

C Perry, O Zuber-Skerritt (eds), Starting Research – Supervision and Training (1992) Chapter 13.

[8] Ibid.

[9] L Conrad, C Perry, O Zuber-Skerritt, ‘Alternatives to Traditional Postgraduate Supervision in the Social Sciences’ in L Conrad, C Perry,

O Zuber-Skerritt (eds), Starting Research – Supervision and Training (1992).

[10] Ibid, who identify a third approach – the supervision committee. This structure usually presupposes that the major responsibility will belong to a single supervisor.

[11] Note 5.

[12] E Phillips and Pugh, How to Get a PhD. a Handbook for Students and their Supervisors (2nd ed, 1994).

[13] R Smith, ‘Potentials for Empowerment in Critical Education Research’ (1993) 20 Australian Educational Researcher 2, 79.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Note 5.

[16] T Bourner and M Hughes, ‘Joint Supervision of Research Degrees: Second Thoughts’ (1991) 24 Higher Education Review 1.

[17] Ibid.

[18] M Pearson and L Ford, ‘Open and Flexible PhD Study and Research – Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs’ (1997) EIP 16, 46.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Note 9.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Examples include the ARC Strategic Plan, the Federal Government’s White Paper on Knowledge and Innovation (IGS, RTS, and RIBG funding), the Federal Government’s Innovation Statement (Backing Australia’s Ability), and most recently the Crossroads discussion papers.

[24] Other policy documents can be found at the QUT Office of Research homepage – Code of Good Practice for Postgraduate Research Studies and Supervision and Guide for Postgraduate Students and Supervisors.

[25] Not available online, but is available on request from the author.

[26] Note 9.

[27] Note 9.

[28] Note 9.

[29] A combination of the 1:1 master apprentice and group supervision approaches.

[30] L Elton, M Pape, ‘The Value of Collegiality’ in L Conrad, C Perry,

O Zuber-Skerritt (eds), Starting Research – Supervision and Training (1992).

[31] D Manderson, ‘FAQ: Initial Questions about Thesis Supervision in Law’ (1997) 8 Legal Education Review 2, 125.

[32] Ibid 2.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid 128.

[36] Ibid 128.

[37] T Hutchinson, Research and Writing in Law (2002) 138.

[38] S Johnston, ‘Professional Development for Post-graduate Supervision’ (1995) 38 Australian Universities Review 2, 19.

[39] This approach of using a brief abstract is used by Geof Hill (See Note 4) although not in a virtual community context.

[40] See Conversation Noel Meyer, Geof Hill, Neville Marsh, Stefan Hornlund commencing 28.05.02. Available from the author.

[41] See Geof Hill’s email dated 19.01.03. Available from the author.

[42] Note 9, 153.

[43] I Moses, ‘Efficiency and Effectiveness in Postgraduate Studies. Assistance for Postgraduate Students: Achieving Better Outcomes’ (Department of Employment, Education and Training, 1987).

[44] Similar arguments were raised in the conversation of Noel Meyer, Stefan Hornlund, Geof Hill, Gary MacLennan, Timothy Ferris commencing 01.04.02. Available from the author.

[45] M Pearson, A Brew, ‘Research Training and Supervision Development’ (2002) 27 Studies in Higher Education 2, 135.

[46] Conversation dated 07.05.02 per Noel Meyer, Geof Hill, and Neville Marsh and email dated 19.01.03 per Geof Hill. Available from the author.

[47] G. Hill e-mail dated 19.01.03 re Cambridge colleagues. Available from the author.

[48] M Pearson, A Brew, ‘Research Training and Supervision Development’ (2002) 27 Studies in Higher Education 2, 139.

[49] See also Ian’s story available from the author.

[50] G Hill, Email to EDN628 students dated 21.11.02. Available from the author.

[51] A Collins, J Brown, and S Neuman, ‘Cognitive Apprenticeship: Teaching the Crafts of Reading, Writing and Mathematics’ in L Resnik (ed) Knowing, Learning and Instruction (1989) 453–494, 457.

[52] Note 48, 140.

[53] Note 48, 141.

[54] J Lave, E Wenger, Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation (1991).

[55] Timothy Ferris conversation dated 4th April 2002. Available from the author.

[56] Note 31, 136.

[57] Note 54, 93.

[58] Ibid 94.

[59] Ibid 94.

[60] Ibid 94.

[61] Ibid 98.

[62] Conversation by Chris dated 19th January 2003. Available from the author.

[63] E McWilliam, P Singh, P Taylor, ‘Doctoral Education, Danger and Risk Management’ (2002) 21 Higher Education Research and Development 2.

[64] S O’Brien, ‘The Lecherous Professor: “An Explosive Thriller about Naked Lust, Perverted Justice and Obsession Beyond Control”’ in C O’Farrell,

D Meadmore, E McWilliam, and C Symes (eds), Taught Bodies (2000)

39–56.

[65] E McWilliam, A Jones, ‘Eros and Pedagogy: The State of (Non) Affairs’ in E McWilliam, and P G Taylor (eds), Pedagogy, Technology and the Body (1996) 123–132.

[66] B Dick, Action Research: Action and Research (2002)

<http://www.uq.net.au/action_research/arp/aandr.html> at 7 March 2003.

[67] Geof Hill used this procedure to recommend a useful article to be added to the website on the topic literature reviews.

[68] Note 57, 102–103.

[69] Note 57, 102.

[70] Note 9, 153.

[71] Note 54, 122.

[72] Ibid.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNELawJl/2004/1.html