University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

[2] In Commonwealth jurisdictions, a similar bifurcation has not yet occurred, perhaps in part because the greater regard for doctrinal analysis constrains such developments. However, many scholars in these jurisdictions have been understandably keen to enrich doctrinal discourse by reference to American scholarship.[6] There are two dangers in this: one is the risk of a literature with essentially undebated theoretical assertions — a replication of American impasses in microcosm — with the particular risk of a doctrine versus theory-policy divide. The other is the danger of missing the opportunity to theorise parts of the Commonwealth inheritance that are not replicated in American law, in particular, the greater incidence of legal fictions and conceptual reasoning. I maintain, as the justification of this article, that by taking this opportunity to theorise parts of the English law tradition, it is possible to simultaneously work to bring doctrinal lawyers closer to those more willing to apply theoretical work.

[3] Perhaps the most important distinction between the Anglo-Australian and American corporate law traditions is the persistence in the former of the entity concept. The notion of the corporation’s separate legal personality has been entrenched at least since the decision in Salomon v Salomon & Co Ltd (‘Salomon’),[7] and had manifested itself in various doctrines prior even to that case.[8] The ‘party line’ for most economists is that the notion of legal personality is a convenient fiction that the law uses to overlay a nexus of contracts; lawyer-economists ascribe to this position almost unanimously. When there has been debate, it has often been in the unedifying terms of ‘contract versus concession’, which had only passing relevance to English law of old, and virtually none to modern law.[9] This has therefore been an important barrier preventing doctrinal lawyers from appreciating that economists have anything useful to contribute to the study of law — it suggests that one of the sides must be wrong.

[4] This article is a study of how an economist and a lawyer might work together to read this persistent riddle. The explanation I offer shows how the legal fiction of the entity concept can mediate between the function of particular rules, and the form that those rules might take to best fulfil their respective functions. Because functions naturally differ from rule to rule, the entity concept itself performs multiple roles. This study therefore requires me to tap a vein of recent policy and jurisprudential analysis of, inter alia, the optimal form that rules should take, the discretion they should repose in adjudicators, and their relation to contracts. In order to do this, I develop a functional taxonomy, which distinguishes between the proprietary and governance functions of the law on one hand, and the definition and alteration of proprietary and governance entitlements on the other. This involves a positivist undertaking: an explanation of how different rules perform these functions and the role of the entity concept in each case. What is interesting about this exercise is that it helps reveal connections and similarities between the function and operation of traditionally separate doctrinal areas. Corporate law ceases to sprawl, and this has expository and pedagogic value, at the very least.

[5] The second part of this study is more controversial. It seeks to use economic theory to provide an efficiency justification of the form and content of the traditional legal rules in at least some of these distinct areas. It is possible to see this as a straightforward normative exercise — an argument for what the law should be, and a criticism of the more prescriptive character of modern law. Alternatively, these arguments might be seen as evidence tending to support the positive efficiency theory of the common law, that is, as part of the claim that non-statutory law has evolved towards efficient rules.[10] One of the reasons I have undertaken this study is to demonstrate to doctrinal lawyers that, quite independently of parvenu reform programs such as the Corporate Law Economic Reform Program (‘CLERP’),[11] efficiency concerns have influenced, or at least have not been at odds with, the emergence of the law. Their absence from the explicit language of judges is not a sufficient objection to this argument.

[6] In Part II of this article, I

show how the development of the orthodox economic definition of the corporation

can be refined.

Part III uses this refined definition of the corporation to

describe the core functions of corporate law. Part IV links this functional

account to a discussion of alternative forms of legal rules, and the efficiency

logic for differentiating form to correspond to function.

One aspect of the

conclusions that may surprise those familiar with the economic debate is the

advocacy of the use of imprecise,

discretionary standards in cases involving the

alteration of governance entitlements. Law and economics research has

traditionally

advocated clear, precise rules, and castigated imprecise rules as

either giving rise to excessive litigation or having rent-seeking

origins. I

develop a worked game-theoretic illustration, which compares a strict rule

against defensive action to a rule taking a

more discretionary approach. This

demonstrates that there may be good reasons to prefer discretionary,

fact-contingent standards

to ‘bright-line’ rules. This is so in

spite of, and perhaps because of, the risk that judges in these areas sometimes

err in selecting the outcome that is ex post efficient. In fact, the incidence

of error may actually have economic value in some

cases. Part V concludes with a

few brief references to some current issues in corporate law to demonstrate the

potential applications

of this framework.

[v]iewing the firm as a nexus of a set of contracting relationships ... serves to make clear that the ... firm is not an individual [but] ... a focus for a complete process in which the conflicting objectives of individuals ... are brought into equilibrium within a framework of contractual relations.[12]

[9] The idea of explaining firms in contractual terms was first formulated by Coase.[13] But Coase never suggested at any stage that this multi-contract explanation was unique to firms. On the contrary, Coase’s paper won the Nobel Prize for demonstrating that the firm’s multi-contract character is analogous to a market. Coase explained some of the important differences between firms and markets, but none of these are summed up in the ‘nexus of contracts’ appellation. As economics permeated other areas of law, these contractual explanations were applied to other legal devices. Thus, a trustee of a trust is also a nexus of contracts or exchange relations, between the settlor and the trustee, the trustee and the beneficiaries, the trustee and lenders to the trust, and so on.[14] Partnerships can also be explained in these terms.[15] So the nexus of contracts concept is principally useful only as a device to debunk the process of attributing to the corporation a set of discrete, discoverable interests separate from those of the contracting parties.

[10] With this

sparse ontology, law and economics scholarship has principally analysed the

governance of the contracts constituting

corporations. Jensen and

Meckling’s enduring contribution was the recognition of contracting

problems, the costs of addressing

such problems, and the governance means

dedicated to economising on

them.[16] But these analyses of

governance simply apply a more general economic theory of contracts. To provide

a total picture of corporations,

and to distinguish this from other areas of the

law on business organisations, we need to add to the contractual theory a

dimension

that describes and defines the property associated with the

contracts.

[12] These insights expand the economic definition of the corporation. One of the characteristics of the corporate form is that the contracts of which it is the nexus are defined by reference to a discrete pool of assets: those to which a corporate entity is recognised as having title.[18] The pool is discrete in two senses. First, the assets to which the corporation’s owners have title do not normally supplement the pool, given limited liability (ie, defensive asset partitioning). Second, as a consequence of affirmative asset partitioning, no claim can be made against the pool of assets unless it lies directly against the corporate entity. These characteristics enable the corporation’s shareholders to secure promises made on their behalf by reference to the assets owned by the corporation. Lenders and other creditors can satisfy their claims from the assets of the company by execution or liquidation, while some of them may have more direct rights against particular assets through security arrangements or other contracts.

[13] Why is this proprietary definition of corporations important? By limiting all claims against the corporation to claims against the assets to which the corporate entity has title, corporations can define their value in a straightforward way. Their value is the value of assets to which they have title, less the present value of claims that properly lie against the corporation. This in turn facilitates the unitisation of that capital into shares (and thus the development of share markets and optimal risk sharing). However, the same is not true of unincorporated firms. For example, the contracts of which a sole proprietor is the nexus are not defined by reference to the assets of the business to which those contracts relate, but to all of the proprietor’s assets. Incorporation thus enables related assets and claims to be coupled with each other, while uncoupling these claims from other, unrelated ones. This plasticity allows great sophistication in the fracturing of and transacting in the risk associated with assets.

[14] It is appropriate to

acknowledge that some economists have emphasised the significance of property

rights in the theory of the

firm, most notably in the so-called ‘property

rights’ literature developed by Grossman, Hart and Moore

(‘GHM’).[19]

GHM argued that a firm is a collection of assets subject to common ownership. I

wish to make three points about this argument. First,

the GHM approach has been

much neglected in the law and economics literature in favour of the nexus of

contracts conception, so there

is little to say about its application to

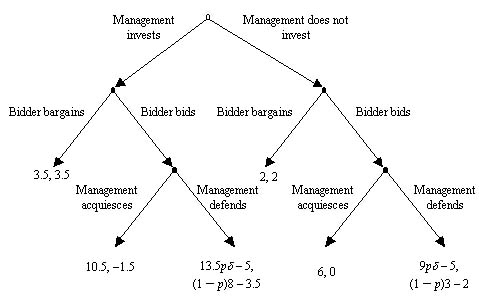

doctrinal

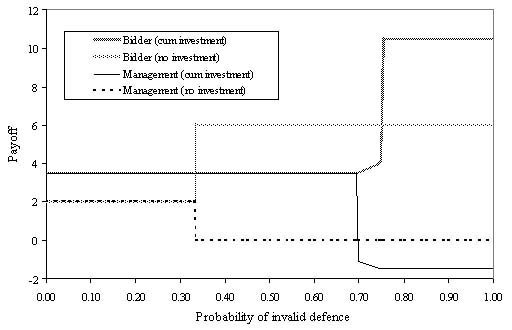

questions.[20]

Second, the emphasis on property rights by GHM is, in fact, justified by the

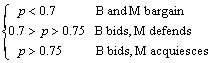

capacity of property rights to serve a governance function.

This logic holds

that in a world where transaction costs are zero, parties would write

state-contingent contracts in relation to

the use and application of

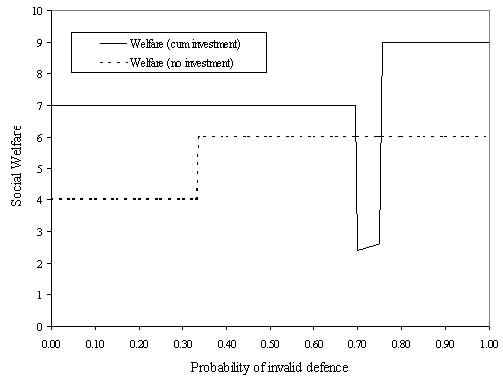

assets[21] and the making of

investments in match.[22] This is

not possible in a world where transaction costs are substantial, and, in

particular, where foresight is imperfect and where

courts are incapable of

verifying the information upon which such a contract would make obligations

conditional. In such a world,

property rights can function as a substitute since

they allow the right to control assets to be allocated between the parties,

subject

to the occurrence of certain contingencies (for example, insolvency or

takeover). This is a powerful insight, but it treats property

rights as

pre-specified and straightforward, whereas lawyers, at least, may be interested

in the legal processes associated with

the definition and alteration of these

proprietary entitlements. Third, GHM’s analysis, like the nexus of

contracts paradigm,

is fundamentally bilateral: it is interested in the role of

property rights in the governance of a relation between A and B. However,

an

enduring characteristic of property rights is that they use constructive (rather

than consensual) rights to enable the rights

of A or B to be effective against

the entire world.[23] The GHM

approach leaves these issues unexplored.

[16] The governance advantages of the corporation are linked to its capacity to partition assets. A well-known advantage of limited liability is that it eliminates the need for mutual monitoring by shareholders, since the value of one’s investment in the firm no longer depends on the collateral and personal assets of the shareholders.[27] The converse proposition is that affirmative asset partitioning eliminates the need for shareholders to protect the assets against the insolvency of, or other forms of default by, other shareholders.[28] Provided, therefore, that there is a sufficiently wide range of substitute investments (in terms of risk-return attributes), the ideal governance attributes of the firm will be independent of the attributes of the shareholders. Those ideal governance attributes will depend only on the corporation’s assets — the property to be governed.

[17] Thus, property and its availability to

satisfy claims are defining features of any particular corporation, and of

corporations

compared to other legal forms. It follows that a corporate entity

must also be important, at the least, as a device which holds property

and

mediates claims against that property. It could be argued that this proves very

little: the corporate entity exists purely because

our concepts of property law

require that title be owned by someone or something. The question, then, is

whether the corporation

does anything more than function as a mere vessel for

title. I evaluate this claim in the following sections.

[19] In attempting to demonstrate that this is in fact the case, it is necessary to recognise an important temporal dimension. A number of features of corporate law, including the capital maintenance rule and the use of majority requirements for voluntary winding up, allow the corporation to function indefinitely as a governance structure for its asset pool. We can therefore look at corporations both as static phenomena at some cross-section in time, but also as dynamic systems that expand or contract. A static analysis describes a system state and the mechanisms adapted to protect it. A dynamic analysis addresses the means by which the system state may change, including the permissible changes and the means that may or must be used to effect the change.

[20] This static-dynamic distinction can be used to

analyse the manner in which corporate law affects the private ordering of the

proprietary and governance aspects of corporations. Table 1 depicts the

structure of the examination. Each of the table’s cells

contains some

aspect of the private ordering of corporations to which corporate law (together

with other bodies of law) is adapted.

My analysis in the following sections

shows how doctrinal areas serve these functions, although these functions are

not hermetically

sealed and do overlap.

|

|

Static Definition

|

Dynamic Process

|

|

Property

|

Corporate endowment

|

Contracting processes

|

|

Governance

|

Corporate governance

|

Regulating transitions

|

[22] These provisions of property law are necessarily supplemented by principles that countenance the lifting of the corporate veil[29] and the imposition of personal liability on officers,[30] both of which function to define corporate property by qualifying limited liability. Legal rules that define the rights of a liquidator to recover conveyances anticipating insolvency reinforce the pool of corporate property. These could perhaps also be described as dynamic rules that regulate transitions, given their inherent association with the period of transition from solvency to insolvency.

[23] There are, however, other important corporate law principles which also serve, in less obvious ways, to define and protect corporate property.[31] These provisions are similar in that they seek to allocate entitlements between the contracting parties, or to narrow the scope of residual control normally associated with property rights. They do this by specifying qualifications on the use of assets in a way that confers certain ‘property-like’ entitlements on the party who does not have residual control over those assets. There are two groups of such corporate laws. The first group is composed of legal rules allocating rights between the residual claimants on the corporate asset pool (the shareholders) and those with residual control. Of these, the most important are fiduciary rules, which allocate property entitlements between shareholders collectively and officers of the corporation.[32] This is obviously true of the corporate opportunity doctrine and equitable duties of confidence,[33] which allocate proprietary entitlements to business opportunities and confidential information. It is also (though less obviously) true of the conflict rule. By providing a prima facie prohibition on contracts in which fiduciaries are interested[34] but permitting the opportunity for fully informed trade with the consent of a majority of shareholders,[35] corporate law protects the assets of the corporation against its directors by means of what economists call ‘property rules’.[36] A property rule requires the owner’s consent to the trade of an entitlement, and is the modal entitlement in most of property law.

[24] The second group of corporate laws that seek to allocate entitlements to corporate assets are those which define and protect the pool of corporate property by controlling the power of shareholders to distribute that property amongst themselves. The most obvious means by which the law does this is through capital maintenance requirements[37] (and other laws on share capital)[38], and through the rules governing dividends. The law thus serves a roughly equivalent function as between creditors and shareholders as fiduciary rules do between officers and shareholders.

[25] The definition and protection of

corporate property is not a good context within which to test whether the

corporate entity serves

purposes beyond being a mere vessel for proprietary

interests and trades.[39] However,

the corporate entity plays an important role in several of the legal rules just

mentioned. For example, the corporate opportunity

doctrine typically refers to

opportunities connected to the corporation’s business or the

fiduciary’s office.[40] Here,

the entity concept is used not to describe interests independent of

shareholders, but to protect the business assets within

the asset pool by

linking the obligation to the process by which the opportunity came to hand.

This process, where the corporation

is used to define the limits of the

protection that shareholders are entitled to expect from the law, is consistent

with the essentially

instrumental qualities of the entity concept. I will return

to similar ideas in the descriptions of the next three functions.

[27] Just as property law per se addresses static property functions, contract law and related areas address dynamic aspects of property. However, there are a number of unique issues that corporate law must address. The first issue is how an entity that lacks a corporeal existence can contract at all. Corporate law resolves this issue through a two-step process. The first step, which I discuss in Part III(C), is to recognise corporate organs, such as the board and the general meeting, which have the capacity to bind the corporation to transactions. The second step is to recognise the grant of authority to officers, employees and agents to transact on behalf of the corporation. The theoretical work on this topic recognises that this body of law should (and for the most part, does) aspire to minimise the costs associated with transactions lacking or exceeding authority.[41] These costs include the damage associated with such transactions (for example, reliance losses), and the costs incurred by parties to prevent such transactions (for example, control investments and search costs). Thus, the law provides efficient principles in order to operationalise the delegation of authority to managerial hierarchies and enable new claims to corporate property to be created.

[28] Corporate law also addresses aspects of the formation of uniquely corporate transactions. Of these, the most important are the transactions that occur in the context of capital formation. Efficient capital allocation is vital to the functioning of capital markets.[42] In addition, the principal terms of the governance contract of the corporation will be established and, via the offering, priced in the initial public offerings of equity securities. In this way, capital formation is crucial to the future governance of the firm — corporate law’s third function.[43] Today, statutory securities law substantially addresses capital formation. However, certain aspects of corporate law addressed these subjects before legislation did. The principal body of law was the equitable obligations of company promoters.[44] The law purports to apply fiduciary principles. However, a closer look at the law’s context and history suggests that the law in this area is concerned with the adequacy of corporate governance processes and the disclosure of information concerning potentially prejudicial transactions.[45]

[29] Similar policy concerns underpin the law on pre-incorporation (or pre-registration) contracts.[46] There is something to be said for the dysfunctional qualities of this area of law, especially as it has developed in the twentieth century.[47] However, in the nineteenth century, the law presumed that the party negotiating the contract was personally liable for its non-performance.[48] That rule encouraged promoters to form the contract through established governance processes — the participants in which might then be held accountable as promoters or as directors in respect of that contract — rather than attempting to bind the corporation as it came into existence. The personal liability rule also addressed a moral hazard problem arising from the uncertainty of what the corporation’s pool of assets actually was: namely, that the promoter would undercapitalise the company in order to breach that contract. Promoters trying to avoid liability contractually would also have to signal the contract’s pre-incorporation status.

[30] The corporate entity has been ubiquitous in the law on corporate agents, promoters and pre-incorporation contracts. Principles that deal with the authority of corporate agents are based on the notion of the devolution of power from the corporation to its active agents and employees.[49] The corporate entity is the beneficiary of the fiduciary duty owed by promoters. Pre-incorporation contracts determine the limits within which the corporation can be treated as the principal. However, the economic functions of these areas of law primarily concern risk allocation, the integrity of governance, and the disclosure of information. They do not imply any separate set of interests to which a legal entity concept might correspond. Does this suggest that the economic accounts are wrong, or that the doctrine is demonstrably inefficient?

[31] There are

inefficient aspects of these areas of law, and all of them have either been

varied or substantially displaced by statute.

I believe, however, that the

entity concept historically functioned in these areas as a device that allowed

innovative judicial responses

to relatively new problems, without affording

judges unlimited licence as lawmakers. In capital formation, for example,

disclosure

was an obvious response to then current concerns about fraud by

promoters.[50] Positing the

corporate entity as an object of a duty allowed judges to employ disclosure

obligations familiar from other areas of

the law. The employment of the concept

of a ‘conflict of interest’ in cases involving promotion had the

advantage for

judges of simply applying the duty to easily verified

circumstances, such as on-sold

assets.[51] They did not have to

create a full-blown duty obliging the promoter to disclose the value of all

assets. Likewise, subjecting agents

to liability for pre-incorporation contracts

was achieved by the instrumental expedient of using a corporate entity. In this

way,

judges could prevent promoters sheltering behind limited liability (in

respect of transactions consummated before the corporation

had a clearly

partitioned asset pool), without articulating a general principle of lifting the

corporate veil. On the other hand,

the entity concept provided a simple means of

avoiding liability by incorporating the company first. It is likewise arguable

that

the law on corporate authority is not a ‘top-down’ imposition

of principles derived by apodictic reasoning from the entity

concept, but a

cautious, incremental response that begins with existing concepts and modifies

them to suit the increasing complexity

of managerial hierarchies. Examples

include the development of such principles as the indoor management

rule,[52] and the equation of

representations of authority with things employees are permitted to do or are

not prevented from doing,[53] both

of which employ the entity concept doctrinally. Thus, the entity concept can be

seen as providing an heuristic method for articulating

complex conclusions

justifiable on other instrumental grounds — an especially valuable method

when it is not clear to what

extent the conclusion should apply to situations

other than that arising in the particular case at hand.

[33] The major areas of law addressing these concerns include the doctrine on the powers and interrelationships of the board and the general meeting, the law governing directors’ powers and duties, and the law governing members’ rights. On the other hand, I have already noted that parts of these bodies of law (including significant parts of the law on directors’ fiduciary duties) protect property rights. This reflects an overlap between the goals of controlling assets and protecting property.

[34] The entity concept pervades these areas of law. A key historical principle which affects standing to enforce rights, and thus, the extent of control over agents, is found in Foss v Harbottle,[54] which employs the entity principle in distinguishing corporate and personal rights. The interests of the ‘company as a whole’ are frequently used to define the nature of the duty the director is expected to discharge.[55] Similar concepts reappear in the law on members’ rights, especially in the context of the power to amend the constitution.[56] The entity concept allows factual considerations to be used to differentiate the way in which legal rules are applied to corporations. For example, cases indicate that whether or not particular behaviour is oppressive to a shareholder can be determined by reference to the nature and history of the corporation.[57] At the most general level, the case law reveals the use of the entity concept to justify a ‘constitutional’ approach to corporations, in which legitimate power is wielded by identified and properly convened bodies according to specified processes, rather than by transient majorities. Despite the fact that shareholders are the ultimate beneficiaries of directors’ duties, courts have refused to treat shareholders as synonymous with the corporation, in order to compel them to proceed constitutionally.[58]

[35] These

various usages of the entity concept have straightforward economic explanations.

First, imposing formal obligations on

the company can be used to establish a

duty to maximise the value of the assets, rather than the welfare of some

individual shareholder

or faction. This is particularly important in cases of

insolvency, when shareholder incentives to maximise the value of assets can

be

perverted and the attractions of wealth transfer are

considerable.[59] Second, referring

to the concept or form of the corporation creates a means of tailoring a legal

rule to the corporation, focusing

particularly on its norms and other aspects of

governance.[60]

This allows for more specific legal rules, an issue I discuss in detail in Part

IV(D). Third, and most importantly, the constitutionalist

approach allows courts

to treat corporations as self-governing systems. Much of the law on constituting

and facilitating governance

has deferred to the exercise of discretion vested in

the board and majority rule in the general meeting. Were the corporation

recognised

simply as a nexus of contracts, this passivity in the enforcement of

rights would have been at odds with the nineteenth century paradigm

of classical

contract law, which identified with precision the required performance and

corresponding remedy. Thus, entity concepts

provided a shell for the emergence

of a kind of contract law that better suited long-term, multi-party

relations.[61] In these relations,

majoritarian governance instrumentalities, while regarded as a principal means

of adjustment over time, were

nonetheless subject to certain limitations to

prevent the power of these instrumentalities from being abused. I consider these

limitations

in the following section.

[37] These issues are therefore transitionary in quality, and it is the regulation of the transition that arouses the interest of the law. Of particular concern is the use of the static governance apparatus itself in mediating these transitions. For example, dynamic governance issues arise in control contests, such as takeovers. Some of the issues that arise in takeovers are basic, contract-like issues of dynamic property, including the disclosure of information and the absence of coercion. Dynamic governance issues intrude upon the use of the static governance apparatus during the takeover (an example of which is the defensive tactics employed by incumbent management). Thus, the exercise of some powers (such as the issuing of shares) is uncontroversial in most cases, but becomes controversial when a contest for control is pendent, since it alters the formal contingency defining management’s control over the firm (that is, the number of shares the bidder must buy to take control). These contrasts provide the justification for a dynamic analysis of governance.

[38] For an example concerned with changing the scope of control, consider the case where a majority seeks to use power, not in dispute in static cases, to alter the ex ante governance structure (ie, contracts and background law).[63] Examples include altering the constitution to empower minority expropriations, changes to the structure of voting rights or the distribution of returns (the latter is an aspect of static property), and various other oppressive tactics carried out under the auspices of governance.

[39] Dynamic issues frequently involve disputes between factions within the corporation and the means (permitted by law) to resolve those disputes. This is an important point because it illustrates one of the main weaknesses of the various justifications of the corporate entity concept. I said in Part III(C) that the entity concept was helpful because it could be linked to the maximisation of asset value. However, this is no longer useful when the issue ceases to involve the use of assets but rather disputation between rival claimants to those assets.[64]

[40] Thus, we might expect that the entity concept would not appear at all in the relevant doctrine. Yet that is not the case. In situations involving directors, probably the single most important set of principles are those associated with the doctrine that powers can only be used for proper purposes — sometimes, it is said, for corporate purposes.[65] The entity concept also surfaces when courts inquire into whether the corporation was better off as a result of the action, since in some of these cases the value of assets will be affected.[66] One notable transitionary case in recent times is the Australian High Court decision in Gambotto v WCP Ltd (‘Gambotto’),[67] in which the Court held that expropriation could only be valid if a proper purpose (ie, one which would benefit the corporation) could be demonstrated. In a takeover case, the capacity of the defensive action to fulfil financing requirements, achieve strategic alliances, or create options for shareholders, could all help to uphold the directors’ action; whereas actions that destroy a majority are more likely to be invalid than those which merely dilute an existing minority interest. Thus, courts often seem to weigh the detriment to the party that currently lacks control against the value added to the assets.

[41] In these cases, Australian courts do not apply fiduciary rules to situations involving conflicts of interest and directors’ duties with anything like the strictness with which they apply them to cases of self-dealing or misappropriation of business opportunities. In the latter transactions, the courts have long emphasised the law’s strictness and inflexibility,[68] and the irrelevance of the merits or justifiability of the transaction.[69] Although judges do not highlight the discrepancy, the reality is that they often tolerate self-interest in these transitionary cases, especially if the benefits associated with defensive action are counted in favour of its validity. Yet there is a difference in approach between Australian and English cases with regard to defensive action. ‘Proper purpose’ cases involving the issue of shares during a control contest in a public company are treated less strictly by Australian courts than English courts.[70] Australian courts rely on a line of authority that looks for an improper purpose but for which the power would not have been exercised.[71] The strict version of the fiduciary principle applied by the English courts is, by contrast, indifferent to motivation or to proof that the transaction would have occurred in any event.

[42] The entity concept therefore frequently

appears in this area of law. It seems, however, that the concept is simply part

of the

highly discretionary approach the law often takes to dynamic governance

cases, and the scope (though not a requirement) for courts

to consider whether

the transaction has explicit welfare-increasing properties. The references to

the entity concept may also be

heuristically valuable, as in the dynamic

property function: they enable courts to resolve issues on a case by case basis,

without

committing to a principle of general application.

[45] A second theme of jurisprudence, emerging from the economics of contracts, is the passivity of the law.[74] Passivity describes the scope for adjudication and the information required for adjudication. There are several hallmarks of passive adjudication, which is particularly associated with the enforcement of relational contracts. First, passive adjudication tends to defer to private ordering, either by enforcing contracts in a literal, formalistic manner, or by treating as authoritative the resolutions reached by governance processes endogenous to the firm or the exchange. Second, background allocation of rights and entitlements will tend to be absolute, or at the least, will not be conditional on factors that are difficult for a court to verify.[75] Passivity is related to simplicity: passive rules are generally a subset of simple rules that restrict the facts and circumstances on which legal rules are based to ones that can be easily verified.

[46] A third theme is understanding how the law varies in its means of recognising and protecting legal entitlements.[76] This is relevant to corporate law because of the importance of property.[77] The conventional distinction is between property rules, which require bilateral consent to the transfer of a recognised entitlement, and liability rules, which enable a party wishing to acquire the entitlement to take it without consent conditional on the payment of compensation. Although the economic analysis of these rules has now become exquisitely complex,[78] it is often thought that property rules have advantages where costs of transacting are relatively low, since they encourage the formation of markets.[79] Liability rules overcome the non-formation of markets where transaction costs are high, but are vulnerable to difficulties of verifying the entitlement’s value.[80]

[47] A fourth theme is the way in which the protection of entitlements varies in the discretion associated with adjudication. Most analyses of liability rules and property rules assume that the grantee and extent of protection is known ex ante. However, entitlements may be allocated ex post using discretionary standards. One might describe a regime which allocates standards in this way as involving contingent, ex post entitlements. One of the most important insights in the economic literature is that contingent ex post entitlements can actually function to encourage parties to contract.[81] Where entitlements are ex ante certain, they can encourage parties to hold out from contracting in the hope of higher offers, where the grantor’s valuation of the entitlement is both variable and unobservable by the would-be acquirer. In these circumstances, the would-be acquirer has only one weapon against hold-out behaviour, and that is to impose delay costs. By contrast, contingent ex post entitlements change the bargaining game. Johnston has modelled the effect of inaccuracy and error in awarding these entitlements.[82] The fact that the highest-valuing entitlement owner is not guaranteed success can actually create the conditions for both parties to agree to ex post efficient trade immediately, rather than after delays. This is because the party wanting the entitlement can reinforce an offer of trade with a credible threat to bypass bargaining by seeking adjudication (which may well leave the other party with nothing), if the offer is rejected.

[48] The final theme of jurisprudence that I wish to advert to here, which is familiar in the economic analysis of corporate law, is the relationship between legal rules and contracts.[83] Default rules permit contrary contracting; mandatory rules do not.[84] The literature discusses various objectives for setting defaults, which can include the saving of negotiation and drafting costs by the provision of rules likely to be preferred by a majority of contracting parties, and forcing parties to disclose private information.[85] Many of the themes and distinctions discussed above can be integrated with these claims.[86] For example, defaults can take the form of standards, such as oppression, which demand some form of contingent ex post adjudication. Defaults can take rule-like form; there is scope for variation in the passivity of these rules, depending on whether the rules have informational motivations. Property and liability rules are important in this context since they are often relevant to violations of unexcluded default rules: liability rules characteristically demand damages; property rules require injunctions and specific performance. A second form of analysing defaults relies on the point in time at which parties actually contract around them. Most corporate law and economics addresses ex ante contracting in relation to the corporation’s constitution and other constitutive documents. In this context, the legal rules so excluded have a contract-like flavour. By contrast, contracting may occur after the initial governance contracts are in place, as, for example, strict fiduciary rules require. The legal rules creating these rights have, in contrast, a property-like flavour.[87]

[49] Many

different forms of law could perform the functions I have attributed to

corporate law. And, indeed, corporate law provides

a multitude of examples of

forms in relation to each function. However, I will argue that each of the main

functions of corporate

law relies principally on a single law form, and that

there is an economic rationale for this correspondence.

[51] The inflexible fiduciary principles applying to self-dealing and expropriation of assets and opportunities also operate in a manner analogous to property rules.[88] These principles deny a right on the part of the fiduciary — like anyone else — to take assets, either with or without compensation. Those rules are appropriately described as property rules because they are not inimical to consensual trade between shareholders and fiduciaries, provided trade is fully informed and non-coercive.[89] Moreover, the property rule description is supported by the remedies for violations of these rules: the creation of constructive trusts or rescission by restitutio in integrum.[90] These are proprietary remedies which do not require the court to value the taking of the assets for the purposes of determining compensation. In this sense, they are also passive rules which make low information demands.

[52] Capital maintenance rules define and protect corporate property by limiting the distributional freedom of shareholders, as mentioned above in Part III(A). These also function like property rules. Legislation historically provided a procedure whereby the creditors could express to a court an opinion about whether a capital reduction could proceed, and there are now other obligations protecting the corporation’s assets.[91] Further, violation of the prohibition is usually addressed by injunctive relief, rather than obligations to compensate.

[53] The law on lifting the corporate

veil defines corporate property by fixing the permeability of defensive asset

partitioning.

The law here transcends the choice between property rules and

liability rules — it addresses the antecedent question of what

property

belongs to the corporation. The sheer infrequency of lifting the corporate veil

in cases other than fraud and statutory

compensation cases suggests that

defensive asset partitioning is strong, which in turn reinforces the other

property rules protecting

corporate assets.

[55] It is also worth mentioning that modern securities statutes also have liability rules built into them to cover cases of culpable false disclosures or omissions. This is a dynamic property issue (rather than a governance issue) since it regulates the process of contracting between the corporation and its investors (rather than being concerned with the control of assets). This use of liability rules has the explicit purpose of deterring interference with the investors’ entitlement to disclosure.

[56] In Part III, I mentioned several important corporate law principles which are also relevant under this heading because they enable contract law to be adapted to the transactions of bodies corporate. The allocation of authority to agents is not explicitly a body of liability rules. However, it functions, as noted above, as a device for risk allocation, which, of course, contract law does also. Historically, those risk allocations were quite blurry, consistent with the heuristic quality I ascribed to the corporate entity in this context. It is notable that where changes have been made to legislation in modern times, they have resulted in much more straightforward risk allocations to the corporation, unless the third party contractor is aware of the violation of authority.[94] There are sound reasons for this, such as the greater capacity of the corporation to force the agent to internalise the cost of unauthorised transactions, and the fact that controlling unauthorised transactions may have a low marginal cost to the corporation given other incentives to install management controls.[95] By creating more easily enforceable obligations against the corporation, these statutes enhance the application of liability rules to contracts with corporations. Similar comments could be made in relation to pre-registration contracts. These also allocate risks, and provide a limited attenuation of defensive asset partitioning by imposing personal liabilities on agents contracting on the firm’s behalf. Again, statutory intervention has been designed to increase the security of these contracts, for example, by allowing the corporation to ratify the contract or by subjecting the agent to personal liability.[96] This increases their similarity with other contracts and enables their enforcement by liability rules.

[57] Promoters’ duties do not fit quite so well with

characteristic liability rules, however, in part because they share remedies

(principally rescission) with other fiduciary

duties.[97] The justification for

this is simply that a liability rule for the breach of promoters’ duties

would be very difficult to apply;

it would require the court to undertake

complex exercises associated with the valuation of businesses, whereas

rescission avoids

the need for such excursions into potentially unverifiable

territory. To the extent that the role of promoters’ duties has

been

displaced by modern securities legislation, their emphasis on compensatory

remedies has, notwithstanding difficult valuation

questions, reaffirmed the

liability rule character of the formation of these contracts.

[59] Many traditional corporate law rules operate in this way. Although fiduciary rules sanction a potentially large role for judicial intervention, other passive rules cut in the opposite direction. First, rules on conflicts of interest were traditionally subject to contract, both ex ante modification (which typically allowed directors to maintain conflicting interests that were disclosed to the board) and ex post trade.[100] Second, the use of rescission as a remedy for conflicts of interest eliminated the incentive to litigate unless the contract was actually welfare-decreasing for the shareholders.[101] Third, the rules on conflict of interest were subject to the rule in Foss v Harbottle, which vitiated the capacity of individual shareholders to litigate these transactions in all but straightforward cases of impoverishment. Fourth, the traditional standard of care of directors was not completely ‘breach-proof’, but its subjectivity made it difficult to breach honestly. (Foss v Harbottle was again a major obstacle to litigating these cases.) Quite apart from these cases of breach of duty, the law has always taken a permissive and passive approach to the exercise of managerial authority by the directors of a corporation;[102] even the recent liberalisation of oppression provisions has not encroached on this liberty, unless its exercise is associated with clear overreaching.[103] Fifth, there is empirical evidence that most companies excluded liability for the standard of care contractually in one way or another.[104]

[60] Legal principles also tend to take a passive approach to the enforcement of majority rule in the general meeting. Apart from rights allocated to shareholders individually (such as the right to vote or to attend general meetings), the exercise by the majority of other rights vested in the shareholders collectively were traditionally subject to very few limitations.[105] These additional rights included the capacity to ratify or affirm any breaches of duty, to agree to allow a director to contract with the corporation, to elect or sack directors, to amend the constitution, and so on. There are limits on these principles, namely the exception to the rule in Foss v Harbottle (fraud on the minority) and the rule in Allen v Gold Reefs of West Africa Ltd (‘Allen’)[106] (fraud on the power), but these seem to be aimed primarily at dynamic governance issues or obvious overreaching.

[61] Passivity has a clear economic justification. Static governance issues are best addressed by endogenous governance structures and norms, not by law.[107] Governance issues raise questions which depend on information that courts find difficult to verify, such as valuations and estimates. Provided claimants on the firm are protected against expropriation and overreaching by the law on static property, and against opportunistic changes to rights and control entitlements by the law on dynamic governance, courts do best to take a minimalist, hands-off approach to governance. This encourages the formation and functioning of endogenous governance structures. The incentive to use governance structures to maximise welfare is usually strong and comes from various sources. In small corporations and in boards, the incentive may derive from the possible development over time of relational norms, such as increased cooperation and mutual identification with organisational goals.[108] In all forms of corporations, the limitations imposed by static property rules on dividends and capital maintenance has the effect of locking the parties into the enterprise. This lock-in effect encourages parties to maximise the value of assets which they share through (typically) fungible equity investments.[109] The willingness to enforce contracts allows parties to tailor their governance structure to intensify incentives or to provide special protection where that is needed. By minimising recourse to courts, the capacity of parties to engage in rent-seeking behaviour is limited, since the capacity to litigate strategically is truncated.[110] If disputes do arise, the use of passive rules with clear and absolute allocations allows the parties to know what the payoffs will be if they fail to reach agreement, which seems to encourage out of court settlement.[111]

[62] We

may observe that both the static governance and static property functions of

corporate law are served by legal rules which

encourage private ordering and

trade and discourage litigation. By contrast, a greater and more complex role

for the courts is preserved

in the enforcement of other contracts and in the

regulation of transitions.

[64] The jurisdiction is thus substantially unique in corporate law, as it relies on contingent ex post entitlements, which other areas of corporate law generally eschew. Although expositions of legal principle do not clearly articulate the nature of the analysis involved in these cases, the courts often appear to be engaged in a form of balancing. The existence of a substantial advantage to the corporation counts in favour of non-intervention, as do actions that have the effect of increasing options for shareholders.[112] Dilution of an existing majority is more likely to be struck down than, say, committing assets desired by a bidder to other, apparently productive uses.[113] Expropriation of shares is prima facie impermissible, although advantages to the corporation may validate it in exceptional cases. In sum, the area is imprecise and discretionary.

[65] The need for some form of law in this area may be conceded. Attempts to use governance procedures to alter control contingencies or to expropriate wealth discourage investment by facilitating opportunism and rent-seeking. Unilateral resolution of factional disputes through governance organs is tainted by self-interest, and the suppression of certain transitions, such as the sale of control, can decrease social welfare.[114] Transitions in governance are also, by definition, ‘final period’ problems, since they alter or transform rights and entitlements fundamentally. Final period problems are frequently associated with the possibility of opportunism, because the parties cease to envisage a future in which they need to cooperate.[115] However, conceding a role to the law does not tell us why the law in this area takes an imprecise form.

[66] Why then, are contingent ex post entitlements pervasive? It is easier to understand first why the earlier forms or solutions discussed in this Part would be difficult to apply to such transitionary events. Passive rules that defer to norms are inappropriate when the situation is one in which norms themselves are undergoing transition, or have so broken down that parties rely on formal governance entitlements in preference to cooperation. Property rules and liability rules depend on the ex ante certain identification of rights and entitlements. One way to achieve ex ante certainty is simply to treat dynamic governance cases in an identical manner as other static governance cases (ie, passively), but that would be to ignore the problems with passivity in dynamic cases. Furthermore, liability rules are vexed by complex valuation questions. These are difficult enough when determining the value of the shares of a minority shareholder, but it would be harder still to quantify, for example, the deprivation of a minority shareholders’ right to participate in meetings since these rights are never traded, except as part of a bundle of rights comprised in the shares.

[67] My first affirmative justification for contingent ex post entitlements relies on their advantages as defaults. It may be true that the law on dynamic governance can be varied by an appropriately specified ex ante contract (for example, one permitting issues of shares in a takeover to facilitate a control auction).[116] There are two arguments supporting the assertion that these legal principles make good defaults. First, more tailored legal principles are preferred where relevant contingencies have a very low risk of occurring (because of the reduced likelihood of ex ante contracting).[117] The ex ante likelihood of any particular dynamic governance configuration is very low. The second argument is that although contingent ex post entitlements can easily be excluded contractually in favour of a straightforward rule, the reverse is not true without the existence of a body of decided case law giving meaning to the rubric employed in cases in this area.[118] A third and related argument is that an imprecise standard has heuristic value, in the sense that it allows more precise precedents to be generated when certain forms of behaviour arise that are undesirable on any view.

[68] My second justification is that this type of rule arguably increases the incidence of agreement when a transition looms. I summarised Johnston’s argument (in Part IV(A)) that these entitlements enable a party to credibly threaten to bypass trade and impose, with positive probability, an uncompensated loss if an offer of trade is rejected. These bargaining properties depend on some imperfection in the balancing of competing merits, and require that the party who offers to trade must incur some costs associated with the attempt to bypass trade.[119] It is not difficult to see these conditions as being met in some dynamic governance cases, especially in cases of expropriation. A balancing test (such as that found in Allen) seems to capture the ‘balancing’ dynamic well. Yet that is not true of the principle articulated by the Australian High Court in Gambotto. In that case, the High Court drew, in my opinion, a dysfunctional and wholly specious distinction between benefits to the corporation from expropriation and benefits to the majority shareholder. That test increases the hold-out capacity of the minority shareholder. However, it is appropriate to note that an imprecise rule may not be optimal in some cases. For example, where ex post efficiencies are likely to be large (as is often true of the profile of minority shareholdings after a takeover), a simple liability rule allowing compulsory acquisition may be superior to either a balancing test or a rule against such acquisitions. This is how most modern statutes resolve the problem.

[69] What

can we say of the use of imprecise principles in takeovers? First, these

principles blunt the sharp edge of the incentive

effects of the hostile

takeover. However, other mechanisms (such as pressure from institutional

investors) may function as a substitute

in this respect, so the net effect is

unclear.[120] Second, legal

principles which provide some scope for defence provide greater security for

those managers who make firm-specific

investments of their human

capital.[121]

In particular, these legal principles enable the directors to make a deal while

they retain control of the company, which increases

their expected returns at

the time they decide to make firm-specific investments. At the same time, the

principles provide an inherent

advantage for bidders who might be expected to

place the highest value on the assets (as a result of economies of scale or

special

technological advantages). This is because courts have the discretion to

favour defence where it encourages some degree of auction-like

competition or,

at least, counter-bids from bidders likely to add value to the

assets.[122]

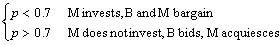

[71] The example studies the optimal rule that should govern defensive action in a takeover. We may consider three different rules that could apply to such defence: a rule permitting any form of defence; a rule prohibiting every form of defence; and a more contingent approach in which defence is upheld as valid with probability, p. We can dismiss the first rule (which no-one has ever advocated): it would effectively destroy hostile bids and cancel an important managerial discipline. Further, the first rule would provide no real incentive for management to make firm-specific investments. The competition is therefore between absolute and probabilitistic prohibitions.

[72] It may be helpful to understand the intuition underlying the following model. I argue that the contingent approach to takeovers is generally superior to the absolute rule because it provides stronger security for the making of firm-specific investments of human capital.[123] This provides a wider range of parameters within which management will defend a hostile bid, which in turn boosts the probability that there will be a deal agreed to by the bidder and management. However, I show one drawback of contingent law — there are a (limited) range of parameters within which parties are actually willing to litigate, despite this being the worst of all outcomes. Litigation does not occur under an absolute prohibition, where management always loses.

[73] The model is undoubtedly a considerable simplification of reality. It does not take into account the possible use of contracts between managers and shareholders to create other incentives for managers to make investments, such as golden parachutes. Nonetheless, contracts are limited in real world situations by the constraints of verifiability. It is also unclear if contracts are more or less likely to occur under contingently specified legal rules or bright-line rules.

[74] There are three time periods in this model. At time 0, managers must make a decision whether or not to make a firm-specific investment of their human capital (eg, by acquiring expertise relating to the firm that adds value to the firm but has zero opportunity cost). At time 1, a bidder decides whether to bargain with management or announce a hostile bid, and management must decide (where there is a hostile bid) whether or not to engage in defensive action. If the parties bargain, they share the gains from trade equally, net of all costs. If management decides not to defend, the takeover will succeed, and management loses the value of its investment and all of the quasi-rents associated with it. In both of these cases, the parties receive their payoffs in time 1. If however, management decides to defend, payoffs are deferred until time 2. At time 2, the court either upholds or strikes down the defensive action. If it is upheld, management remains in control; if struck down, the takeover succeeds.

[75] Let the cost of management’s investment equal $1.5. Let the cost

to bargain be $1 to each party, the cost to litigate be

$2 to each party, and

the cost to bid be $3 to the bidder. Let δ = 0.9, such that the

present value of $10 at time 2 equals $9 in time 1. Let the gross gains from the

takeover where management makes

its investment be $13.5, and $9 where no

investment is made. From this, we can see that the investment produces an

appropriable quasi-rent

of $4.5, being $13.5 − 9. Let the private

value to management of remaining in control be $8 where management has invested;

otherwise, it is $3. Finally, if management defends, the bidder litigates the

case and succeeds with some probability, p. Where the law absolutely

prohibits defence, p = 1. If management defends and wins, it earns the

payoff associated with control.

[77] What is the solution to the ‘invest subgame’ on the left

hand side of Figure 1? Where p < 0.75, management is better off

defending than acquiescing.[124]

The bidder is better off bargaining than bidding for all p >

0.7.[125] We therefore have the

following equilibrium:

[79] In the

‘does not invest subgame’, the solution is more

straightforward:

[82] It follows that in this game, litigation never occurs (technically, it is not subgame perfect). Welfare equals $7 where p < 0.7, and $6 where p > 0.7.[130] To conclude, in this example, the highest attainable social welfare is under a rule in which defensive action is permitted in at least some cases, since it provides a positive incentive to invest.

[83] The point of this demonstration is to

show how a legal regime equidistant from those permitting defence and those

requiring managerial

passivity can provide better incentives than either.

Although the factor driving the specific results in this example is

management’s

investment, the example is consistent with a much more

general point: transitions are highly complex events in which merits vary

greatly, and which the law needs to approach flexibly. Incentives could be

improved even further if the value of p varies in direct

proportion to the

magnitude and value of firm-specific investments. Variability is also necessary

if courts are to be able to distinguish

the use of governance processes from

their abuse — that is, if they are to recognise the static governance

cases from amongst

the dynamic governance cases.

[86] In this article, I have addressed the weaknesses of both approaches by bringing elements of each together. The first step lies in bringing to the foreground corporate property: corporate contracts define various claims to it, and performance of such contracts transforms that property over time. Yet economic theories have only begun to address proprietary issues, and much of the property law analysis remains incomplete. The essential lines of inquiry lie in the definition and protection of property, and in the means by which contracts affecting that property are entered into. These are not purely questions of property and contract law; they raise unique corporate law issues worthy of theoretical treatment, in addition to their many doctrinal implications.

[87] Concern with governance is, of course, firmly established in modern policy and scholarship. But the subject is not a wholly happy one, for we vacillate between the deregulatory, minimalist credo of economists and the willingness of modern regulators to intervene in private ordering. The answer lies not in striking a ‘balance’, and justifying some mandatory law as consistent with a mixed economy,[131] but in more appropriate distinctions between governance issues in terms of the circumstances in which the state can play a meaningful role. The critical juncture I have identified in this article is in important transitions, especially in the use of governance processes to suppress or promote these transitions or to vary important parts of the static governance structure of the firm.

[88] I have argued that, seen in these terms, corporate law principles have, at least traditionally, been sharply differentiated. Static property issues have employed principles that define and protect the corporation’s property rights. This explains the literal treatment of the corporation as an entity, since it most easily facilitates the identification and transfer of title. It also explains the use of inflexible principles subject to ex post permission in areas as divergent as fiduciary duties and capital maintenance. Dynamic property issues utilise the liability rules of contract law and corporate law principles designed to allocate risks in a way that is most consistent with the working of the market. In this area, corporate law has faced complexities; the entity concept has functioned as a heuristic model for working these principles out. Statute, however, is playing an increasingly important role, often simplifying the application of the somewhat complex and occasionally dysfunctional characteristics of the common law.

[89] The hallmark of much of corporate law’s relation to governance is passivity, and thus self-enforcement. Self-enforcement can be facilitated through passive deference to the operation of governance structures and by the static property functions of corporate law that lock shareholders, as a body, into corporations. The parties remain at liberty to enforce any explicit deal they may agree to. Corporate entity concepts function instrumentally in this area, by standing in the place of the value of assets, and also by legitimating the importance of constitutional structures to which the law may defer. The fault line that separates passivity from intervention becomes relevant in the areas in which normative and governance systems are transformed — what I have called dynamic governance issues. Here, traditional corporate law had developed a more discriminating ex post jurisdiction. It allocated ex post contingent entitlements, a jurisdiction I have advanced tentative economic justifications for, both in its flexibility as a regulatory standard and in light of its incentive to enter ex post efficient trade.

[90] Apart from its value in clarifying the connection between the entity concept and the economic analysis of corporate law, my analysis has, at the very least, suggestive value for various contentious policy issues. For example, it affirms the orthodox economic scepticism of the value of an intensified standard of care for directors, unless it is coupled with an explicit freedom to contract for releases of liability in cases where overreaching is not involved. Second, it suggests that attempts to widen the scope for derivative suits by directors is substantially undesirable, in part because there are few rights shareholders should desirably enforce by way of liability rules, and in part, because the blurred quality of the key exception, fraud on the minority, is something the law should preserve. However, my analysis is by no means a complete defence of the ancien régime. The entity concept’s value as a heuristic tool should not blind us to the fact that it often failed to achieve its purpose, especially as judges came to apply it as a formalistic concept, requiring legislative intervention in areas such as ultra vires actions and pre-incorporation contracts.

[91] To

conclude, it is clear that economic analysis has unnecessarily divorced itself

from the entity concept. The entity concept

provides a way of analysing the role

of property in a theory of the incorporated firm. The concept generally has

played a vital part

in the evolution of corporate law, pushing the law towards

efficiency. The ontological imprecision of the concept allows it to take

a role

in discrete functional areas of corporate law and to support quite distinct

legal forms. The law accepts fictions that resolve

important questions: both

economic and legal formalists would do well to understand this characteristic

before venturing either to

dismantle or overload the current law.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJl/2001/13.html