University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

BRYAN HORRIGAN[*]

Few trends could so thoroughly undermine the very foundations of our free society as the acceptance by corporate officials of a social responsibility other than to make as much money for their stockholders as possible.

-- Milton Friedman.[1]

Good corporate citizenship is good business practice.

-- Mohan Kaul, Director-General of the Commonwealth Business Council, 2001.[2]

The idea of corporate social responsibility (CSR) poses a threat to free enterprise. The [so-called] solution is a new model of capitalism based on the principle of environmentally sustainable development. This is a principle that is ill-defined and potentially harmful because there is no attempt to recognize the substantial costs involved and set them against the (often small) benefits. Businesses, most notably the large MNCs [multinational corporations] most subject to the demands of CSR, have sought to appease their critics. The greatest potential for harm comes from the attempt to impose global governance — common international standards across widely different countries — which can only cripple international trade and investment flows and hold back the poorest countries.

-- Alan Wood, Economics Editor, The Australian.[3]

Do companies have social consciences or is that treating them wrongly, as moral agents, like human beings? What impact does the legal and moral status of companies have on their social responsibilities? On a systemic view beyond individual companies, is it true that ‘capitalist economies cannot work without a moral foundation [and] without a “critical mass” of moral people running them’?[4] Are the best interests of a corporation and its shareholders ultimately and predominantly financial in terms of shares and profitability, or is that too reductionist and simplistic? Can business choose profits and people or must it choose constantly between profits over people or people over profits? How might any corporate social responsibilities be integrated with good organisational governance? What does it mean to be a ‘triple bottom line’ organisation?[5] Is there any connection between recent corporate collapses and inadequacies in meeting corporate social responsibilities?[6]

All of these questions revolve around the links between corporate governance and corporate responsibility. Those links are important, as not all of the corporate governance reform suggestions emerging in the light of corporate collapses like Enron, HIH and One.Tel address wider notions of corporate social responsibility. The federal government’s suggested reforms on corporate disclosure and audit regulation — the latest instalment of its Corporate Law Economic Reform Program (‘CLERP 9’) — fit this description. Equally, much remains to be done in translating the ideals of corporate social responsibility into something that both meaningfully relates non-shareholder interests to corporate concerns and translates ‘triple bottom line’ thinking into meaningful social, organisational and individual indicators of performance and well-being.

Accordingly, this article focuses on some key fault lines in the intersection between corporate governance and corporate social responsibility. It explores some ways in which a shareholder-based focus can undervalue the importance of non-shareholder interests on various levels. It also explores how a stakeholder-based focus can be deficient if it does not justify the link between non-shareholder interests and corporate responsibilities. Finally, it offers some practical suggestions for better aligning corporate governance to ‘triple bottom line’ indicators. The clear themes running through this article can be stated briefly. Corporate governance is moving gradually but haphazardly in a direction which is more, rather than less, favourable to notions of corporate social responsibility and ‘triple bottom line’ performance. Mono-dimensional views of corporate interests in terms of a zero-sum approach to shareholder and stakeholder interests, in which a gain for one is a loss for the other, are inadequate to meet the complexities of corporate regulation and governance. The development and alignment of adequate economic and non-economic indicators across societal, organisational and personal performance levels is necessary to embed ‘triple bottom line’ literacy in regulatory and corporate thinking and practice.[7]

The relationship between corporate governance and social responsibility suggests ten simple but powerful starting points for this article. First, as a human enterprise, capital is not mono-dimensional. Rather, it also encompasses economic capital, human capital, moral capital, intellectual capital, social capital and environmental capital. Second, as shown by the corporate disasters involving Enron, WorldCom, One.Tel and HIH (among others), the exploitation of financial capital happens within a regulatory system based on trust between market participants, especially in terms of board dynamics, market information, and corporate reporting and disclosure. Third, equal attention to socioeconomic and environmental capital, as urged by ‘triple bottom line’ advocates, reveals the deeper connections and symbiotic relationships between the various forms of capital. Fourth, a respectable body of academic and business opinion increasingly views corporate governance and the bottom line not only in terms of compliance, shareholder interests and profits, but also in terms that make those things interdependent with other societal interests. Fifth, this means that, increasingly, modern corporate governance considers dimensions broader than conventionally thought or practised. It focuses on delivering different but interdependent outcomes for shareholders and stakeholders in response to regulatory, environmental, and socioeconomic dynamics and challenges, as opposed to focusing simply on linear connections between companies, profit-making, stock values and shareholder returns in isolation. This interdependence between shareholder and stakeholder interests, on the one hand, and between the different regulatory, financial, socioeconomic and environmental components of the corporate bottom line, on the other, is a key influence reframing ideas about the relationship between companies, shareholders, stakeholders and society.

Sixth, this broadening of the dimensions and elements of corporate governance also means taking a more complex view of the different dimensions of capital and their interactions. Seventh, while much fuzzy thinking surrounds the underestimation by some businesses and the overestimation by some social activists of the impact of socioeconomic and environmental factors upon the financial bottom line for companies, reframing both the notion of a bottom line and the relation between its components is necessary to meet the new awareness of this interdependence between different forms of capital and between the interests of shareholders and stakeholders in corporate governance. Increasingly, rhetorical battles framed in simple terms of a pure dichotomy or competition between shareholder-centred financial capital and stakeholder-centred socioeconomic capital are boxing at shadows. The important issues lie elsewhere, framed in terms of a network of interdependent factors and relationships supporting profitability, shareholder value and business sustainability. Eighth, the rise and significance of different forms of regulation suggests what some call a ‘quadruple bottom line’ emphasis for companies. This focuses on the dynamic interaction between components which cover financial, socioeconomic, and environmental concerns, as well as governance and regulatory concerns.[8] The dimensions of corporate governance must accommodate such shifts in thought and action. Ninth, effective corporate citizenship needs the stimulus of a coordinated legislative, co-regulatory and self-regulatory response to the relationship between companies, shareholders, stakeholders and society. Finally, the challenge remains to develop and translate meaningful indicators of social and economic prosperity into meaningful performance measures at organisational and individual levels as part of the implementation of good governance.

Both the global landscape and the corporate mindset are changing from wholly economically-centred decision-making to decision-making based on a wider horizon of integrated interests. Futurist Robert Theobald puts the shift starkly:

the required success criteria for the twenty-first century are ecological integrity, effective decision-making, and social cohesion. These are progressively replacing current commitments to economic growth, compulsive consumption, and international competition.

This change in success criteria will necessarily occur at the personal, group, and community level rather than through top-down policy shifts.[9]

At present, some public and political conceptions of corporations and their interests are framed in narrow, one-dimensional terms of self-interest and profit, as when the basic duty of directors to act in a company’s best interests is translated solely into maximising share value and dividends for shareholders. Moreover, executives and managers of government corporations and non-government corporations alike are perceived publicly and in boardrooms as being preoccupied solely or predominantly with ‘the bottom line’, measured largely or wholly in terms of profit maximisation, share prices, and financial returns to shareholders, and clothed sometimes in rhetoric about business sustainability and shareholder value. However, if the interests of both shareholders and non-shareholders are multi-dimensional and those interests are interdependent, and if corporations involve a managed network of internal and external relationships which reflect such realities, the best interests of corporations and their shareholders cannot be structured one-dimensionally in a linear relationship between managers and owners. A tension still exists in public and academic debate between the harsh realities of corporate regulation, directors’ duties, profit-making and shareholder returns, on the one hand, and the ideals of the movement towards ‘social charters’, ‘triple bottom lines’, and other indicators of corporate citizenship and social responsibility, on the other. Indeed, recent Australian surveys suggest a low level of understanding in the business community of what it really means in practice to become a ‘triple bottom line’ corporation.[10]

The debate about corporate citizenship is positioned within a wider ideological and global debate, although one might not guess this from the heavy emphasis in Australian corporate and political debate on matters such as minimising governmental regulation of business, maximising shareholder value, promoting investor security, catching corporate renegades, enhancing competition, creating business sustainability and responding to market needs. Internationally, on one view, this is part of a much wider divergence in views between two transnational movements — the corporate globalisation movement and the living democracy movement.[11] Under this vision, the corporate globalisation movement comprises an alliance between the world’s largest corporations and most powerful governments. The purpose of this alliance, it is said, is:

to integrate the world’s national economies into a single, borderless global economy in which the world’s mega-corporations are free to move goods and money anywhere in the world that affords an opportunity for profit, without governmental interference. [12]

An ancillary aim of this alliance is to privatise public services and assets as well as strengthen safeguards for investors and private property. Its proponents justify its expansion as

the result of inevitable and irreversible historical forces driving a powerful engine of technological innovation and economic growth that is strengthening human freedom, spreading democracy, and creating the wealth needed to end poverty and save the environment.[13]

In contrast, the living democracy movement comprises a ‘newly emerging global movement advanced by a planetary citizen alliance of civil society organisations’[14] who believe that:

corporate globalisation is neither inevitable nor beneficial, but rather the product of intentional decisions and policies promoted by the World Trade Organization, the World Bank, the IMF, global corporations, and politicians who depend on corporate money.[15]

It is further said that:

corporate globalisation is enriching the few at the expense of the many, replacing democracy with rule by corporations and financial elites, destroying the real wealth of the planet and society to make money for the already wealthy, and eroding the relationships of trust and caring that are the essential foundation of a civilised society.[16]

On this view, citizenship and individual-centred orientations are, for corporations and governments alike, displaced by narrow economic methods of assessing individual worth and organisational performance as well as by the institutional impact of globalisation, corporatism and managerialism.

Of course, other characterisations are possible in describing the competition between economic and non-economic interests, motivations, and responsibilities for governments, business and the community. For example, some characterisations turn on the tension between economic and socio-environmental interests, while others view the tension as being between shareholder and wider stakeholder interests. Of course, framing economic and social interests in oppositional terms ignores their capacity to accommodate each other. Nor is there a simple contrast between shareholders and stakeholders, given the multiple ‘hats’ worn by both individual and institutional shareholders, as well as the qualitatively different interests of ‘inner circle’ stakeholders like employees, customers and creditors compared to ‘outer circle’ stakeholders like regulators, interest groups and the wider community.[17] Much of this debate is reflected in the distinction between ‘single bottom line’ thinking, on the one hand, and ‘triple bottom line’ thinking and corporate social responsibility on the other.

Do the best interests of corporations and shareholders equate simply to profit-maximisation, share values and financial returns to shareholders? When we examine closely the ways in which the law regulates directors’ duties, we find the overriding regulatory rationale is to promote directors and other officers acting in the best interests of the company overall. The real question is what that primary directive translates into in practice. Conventionally, the best interests of the company equate roughly to the best interests of the shareholders, and that in turn usually translates into profitability, enhanced share price and dividends. Yet that assumes much about the ‘right’ conception of a corporation in legal terms, especially in terms of a compact between a corporation and its members, regardless of other interests (including wider stakeholders).

Why is political debate about corporate and public affairs so limited in its focus and so blinkered in its uncritical acceptance of prevailing dogma in corporate regulation and corporate and legal practice? Some commentators argue that the new politics of law and government involve maximising business and market interests and minimising political and corporate responsibility for social well-being. For example, Australian corporate regulation traditionally views companies mainly in terms of maximising profits and shareholder returns rather than building social capital, as if those interests are mutually exclusive. On a more rigorous level of scholarship, philosophical argument continues amongst corporate philosophers about the relational, contractarian, economic and other jurisprudential rationales for corporate law and regulation.[18] Recent scholarship challenges intellectuals to question the extent to which their own scholarship and work is wholly business-orientated and uncritical, simply serving the managerial interests of vocational training and technocratic credentialism in universities[19] as well as the economic and market interests of business as part of the financialisation of public policy in the new politics of law and government.[20]

Neither organisations nor individuals are likely to take corporate social responsibility seriously as part of their core business unless it is effectively integrated within corporate governance. This is an important connection. Corporate governance is one of those fundamental yet nebulous concepts which many claim to understand and implement but which few can define comprehensively or even succinctly.[21] Historically, corporate governance has sometimes narrowly been conceived simply in terms of ‘the relationships between the firm’s capital providers and top managers as mediated by its board of directors’.[22] Today, it is defined variously in terms of structures and processes, direction and control, substantive elements like performance and compliance, or managing the multiplicity of internal and external corporate relationships. In both regulation and practice, more emphasis is often placed on corporate governance in the narrow sense of the relationship between a company’s shareholders, managers and directors than on corporate governance in any wider sense of responsibility to stakeholders.[23] Of course, there is also a need to distinguish between the different nature and requirements of ‘public governance’ (ie, governance as it relates to governments and the governance and regulation of communities), ‘organisational governance’ (ie, the governance of organisations generally and not just corporate bodies, in both the public and private sectors), ‘corporate governance’ (ie, the governance of governmental and non-governmental corporate entities, informed significantly by private sector experience of boards and corporations) and ‘personal governance’(ie, managing governance at the individual level, including translation of organisational governance concerns, strategies and performance indicators into matters of individual responsibility within organisations).

In the private sector, corporate governance is often discussed in terms of the core areas of board responsibility: strategy, performance, resources, conformance (eg, compliance) and accountability (to shareholders). Ian Dunlop, the CEO of the Australian Institute of Company Directors, usefully characterised these core areas in the following terms:

• strategy: to participate with management in setting the goals, strategies and performance targets for the enterprise;

• performance: to monitor the performance of the enterprise against its business strategies and targets, with the objective of enhancing its prosperity over the long term;

• resources: to make available to management the resources to achieve the strategic plan – the money, management, manpower and materials;

• conformance: to ensure there are adequate processes to conform with legal requirements and corporate governance standards, and that risk exposures are adequately managed; and

• accountability to shareholders: to report progress to the shareholders as their appointed representatives, and seek to align the collective interests of shareholders, boards and management. 24

This is not the only conceptual map available. Corporate governance in the public and private sectors has a number of other dimensions. These additional elements are outlined in the framework suggested below:

(2) Ownership governance, eg, ‘owners’ and multiple agencies and constituencies;

(3) Structural governance, eg, two-tiered watchdog and governance boards;

(4) Strategy governance, eg, corporate plans for government business enterprises;

(5) Performance governance, both organisationally and individually, encompassing process, outcomes and measures;

(6) Conformance governance, including compliance, due diligence, financial risk management and legal risk management;

(7) Decision-making governance, including internal and external relationship management and communication;

(8) Primary accountability governance (owners and shareholders);

(9) Secondary accountability governance (stakeholders); and

(10) Value-capital enhancement, including long-term sustainability of various forms of corporate capital, as well as ‘triple bottom line’ emphasis on economic, environmental and social capital.[25]

Of course, elements relating to corporate social responsibility are not confined to the latter dimension alone but cut across other governance dimensions too.

One weakness of many such lists of the elements, concepts, or dimensions of corporate governance is the absence of synchronicity between the components in the list. It is one thing to identify components of governance and another thing altogether to show how those components relate to one another. Allens Arthur Robinson partner Steven Cole suggests a working definition of corporate governance which synchronises, integrates, and otherwise aligns the various components. His preferred definition is:[26]

The SYSTEMS AND PROCEDURES by which corporations are controlled and governed, involving the roles of:

and their CULTURAL INTERFACE with:

to deliver ACCOUNTABLE CORPORATE PERFORMANCE in accordance with the corporation’s GOALS AND OBJECTIVES.

Given my own view of the dimensions of governance, I would incorporate Cole’s definition (along with the views of governance commentators like Kiel and Mills) in the following formulation of a definition of corporate and organisational governance which emphasises the linkages between its various components:

Through ongoing SHARED UNDERSTANDING AND AWARENESS-RAISING, organisations achieve good corporate governance by ALIGNING, SYNCHRONISING, AND INTEGRATING the various STRUCTURES, SYSTEMS, PROCESSES, PRACTICES, AND PLANS by which the organisation is DIRECTED, CONTROLLED, AND MANAGED (ie, GOVERNED), involving the collective and individual ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES of:

• the Board;

and their CULTURAL INTERFACE AND RELATIONSHIPS with:

• individual directors;

• senior executives and managers; and

• staff

• one another;

to deliver:

• management generally;

• shareholders;

• ‘inner circle’ stakeholders (ie, employees, customers, creditors, financiers); and

• ‘outer circle’ stakeholders (ie, regulators, industry peers, governments, and the community);

• TRANSPARENT, MEASURABLE, AND ACCOUNTABLE CORPORATE PERFORMANCE; and

for the organisation’s SHAREHOLDERS AND STAKEHOLDERS by meeting challenges, exploiting opportunities, and managing risks derived from:

• SUSTAINABLE VALUE-CAPITAL ENHANCEMENT;

• politico-regulatory factors;

in accordance with the corporation’s GOALS, OBJECTIVES, AND STRATEGIES in customised ways which translate to all organisational levels and which are effectively MONITORED, EVALUATED, AND REPORTED.[27]

• financial factors;

• socioeconomic factors; and

• environmental factors;

In this way, organisational and individual governance responsibilities integrate politico-regulatory, financial, socioeconomic and environmental concerns in a holistic way which flows through to strategic planning, performance and corporate outcomes. Indeed, this integration of regulatory, financial, socioeconomic and environmental concerns is one thing prompting some commentators to suggest that corporate governance should be moving from ‘single bottom line’ and ‘triple bottom line’ frameworks to ‘quadruple bottom line’ thinking. Indeed, if we distinguish between politico-regulatory and governance concerns as distinct interests worthy of inclusion in ‘bottom line’ thinking, we start to move towards a multi-dimensional quintuple bottom line. Others counter that the real point for business is to show how ‘triple bottom line’ concerns translate in terms which affect and relate directly to the single bottom line, conceived largely in financial and economic terms.

This synchronisation of governance elements also has an impact on the conception of corporate and board responsibilities. To govern a corporation in a way which promotes sustainable corporate viability and value in response to the risks, challenges, and opportunities generated by financial concerns, politico-regulatory dynamics, socioeconomic factors and environmental interests is to govern in a way which frames those responsibilities beyond a simple dichotomy between shareholder and stakeholder interests. It responds to internal and external organisational pressures and dynamics which structure and influence corporate behaviour. It takes the analysis and practice of governance beyond arguing how and why companies have responsibilities to shareholders, stakeholders and communities.

Similarly, the relationships between the different forms of capital and between shareholders, ‘inner circle’ stakeholders and ‘outer circle’ stakeholders can form the basis for alternative formulations of corporate responsibility beyond simple shareholder-stakeholder and contractarian-communitarian models. For example, Margaret Blair and Lynn Stout suggest a ‘team production approach’ as an alternative to ‘the prevailing principal–agent model of the public corporation and the shareholder wealth maximisation goal that underlies it’ because of a ‘shareholder primacy norm’ deeply embedded in corporate regulation and thinking.[28] Under their approach, the ‘internal governance structure’ for corporations relies on a ‘mediating hierarchy’ with a board of directors at its apex, in which the interests and rights of both shareholders and non-shareholders are mediated through the corporation as a separate legal entity rather than exercised directly by them.[29] On this view, corporate success as a collective enterprise rests on the combined and coordinated investment, input and interests of a team of shareholders and non-shareholders such as executives, employees, creditors and local communities in which corporations do business, ‘to protect the enterprise-specific investments of all the members of the corporate “team”’.[30] Accordingly, directors are insulated by the ‘mediating hierarchy’ from direct control by shareholders and stakeholders, instead being responsible for the ‘corporate coalition’ of interests as their corporations ‘mediate among the competing interests of various groups and individuals that risk firm-specific investments in a joint enterprise’.[31] Moreover, people involved in corporations do not simply exhibit self-interested behaviour except as restrained by external sanctions, but rather are influenced and socialised internally ‘through social framing that encourages officers, directors and shareholders to view their relationships as cooperative ones calling for other-regarding behaviour’, thus creating ‘internalised trust and trustworthiness … encouraging cooperation within firms’.[32]

Critics of this alternative approach point to its descriptive inability to explain current corporate regulation’s primary focus on the shareholder and to its normative inability to produce better distributional outcomes for non-shareholders. Whether viewed in market-based, contract-based, relational, or team production terms, the board’s mediation of the competing claims of shareholders and non-shareholders to limited corporate resources rests on the merits of those claims and the board’s willingness to accommodate them.[33] On a critical view, the team production approach ‘does nothing to improve the extra-legal status of non-shareholders in relation to shareholders’ and hence ‘there is no reason to expect improvements in distributional outcomes’.[34] Accordingly, this alternative approach ‘does not advance progressive efforts to construct a broader understanding of management’s responsibility to non-shareholders aimed at improving distributional outcomes currently available through market interactions’.[35]

Such criticisms frame shareholder and non-shareholder interests largely in oppositional terms, focused mainly on the competing demands for allocating scarce corporate resources. They are contingent on particular views of responsibility (eg, board responsibilities to others), accountability (eg, sources of corporate accountability beyond ownership), regulation (eg, the legal status of non-shareholder interests) and market dynamics (eg, the extra-legal force of non-shareholder interests). The validity of such criticisms turns not only on the absence of mandatory legal enhancement of non-shareholder interests relative to shareholder interests, but also on the minimal impact of non-shareholder interests on both market dynamics and board decision-making in terms of the importance and power of non-shareholders beyond simply their capacity to bargain. It also rests on a minimalist view of the interdependence of shareholder and stakeholder interests, not least in terms of the alignment and synchronisation of governance dimensions in corporate responses to internal and external risks, opportunities and dynamics as outlined above.

In the governance literature, corporate governance is clearly being perceived more broadly than in conventional thinking and practice in many business and governmental organisations. For example:

corporate governance is more than simply the relationship between the firm and its capital providers. Corporate governance also indicates how the various constituencies that define the business enterprise serve, and are served by, the corporation. Implicit and explicit relationships between the corporation and its employees, creditors, suppliers, customers, host communities — and relationships among these constituencies themselves — fall within the ambit of a relevant definition of corporate governance. As such, the phrase calls into scrutiny not only the definition of the corporate form, but also its purposes and its accountability to each of the relevant constituencies.[36]

Why might it be necessary to broaden the focus on corporate and organisational governance in this and other ways? First, shareholder interests have a symbiotic relationship with other interests, so attempts to compartmentalise and straitjacket governance wholly within a particular kind of shareholder-based vision is illusory, not least because a shareholder-based focus can still embrace and relate to other interests. Second, whatever arguments might be made about the different definitions and dimensions of governance, things beyond the orthodox notions of strategy, performance, conformance and accountability (to shareholders) risk being marginalised unless they are given equal prominence and priority as distinct dimensions of governance. Third, the dimensions of accountability to shareholders and stakeholders are qualitatively different in their own right and in their application to different organisations in the public and private sectors. Fourth, for directors and their internal and external advisers, it is also imperative to ensure that legal risk management and compliance — important as they are — do not become the ‘tail’ which wags the good governance ‘dog’. Fifth, governance-talk must accommodate changes in the emphasis, priorities and features of governance thinking and practice to include meaningful reference to notions like ‘triple bottom lines’, ‘balanced scorecards’ and ‘auditing for social outcomes’ as well as developments in stakeholder analysis and regulatory accountability. Finally, the similarities and differences in the legal regulation of government corporations, non-government corporations which service governments, non-government corporations which service business and the community, and cooperative ventures between government corporations and non-government corporations all need attention on dimensions of governance which are not limited to conformance, compliance and risk management, whether under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), State and Territory corporatisation and business enterprises legislation, general laws like the laws of trade practices and contract, or even specific laws like the Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997 (Cth).

All of this also assumes that ‘best practice’ governance has a demonstrable impact on corporate performance, investor perceptions and stakeholder reactions. The evidence for this is patchy and is dependent on some in-built assumptions about the relation between these elements.[37] For example, does creating supervisory boards and committees, having more genuinely independent directors, rotating audit firms or partners for audit and non-audit work, or mandating corporate governance committees or codes have an appreciable impact on overall corporate performance? However, any mixed evidence about the precise relation between corporate governance and corporate performance must also account for the implications of bad governance. It might be clearer after recent corporate collapses that, even if good corporate governance is no guarantee of good corporate performance, corporations which fail often have inadequate corporate governance on some level, which suggests that good governance is a necessary but not sufficient condition for good performance. Moreover, a close relationship exists between corporate governance and legal duties and obligations.[38] While there is no absolute legal obligation yet in Australia to implement a prescribed system of corporate governance, apart from reporting within regulatory guidelines on whatever system of governance is in place, failing to have good corporate governance might lead to a breach of the duties of care and diligence and to other liabilities for corporate personnel.[39]

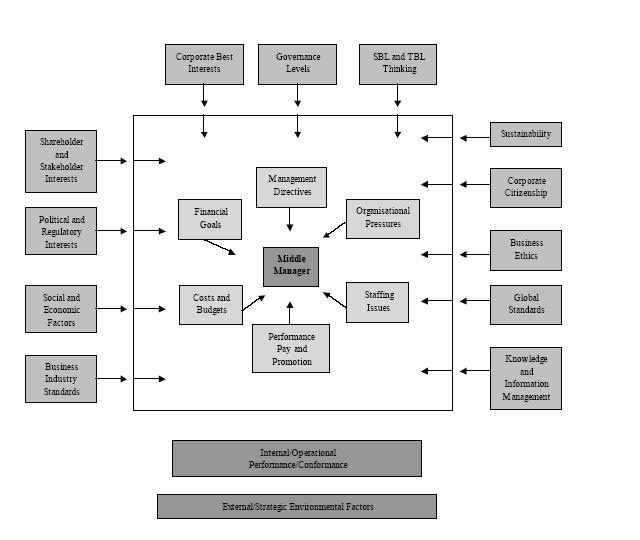

At a practical level, one of the hardest things for everyone from boards and directors, at one level, to managers and staff, at another level, is to relate the external and strategic environmental factors for an organisation to its internal operations. For many middle managers and staff, even in the most enlightened organisations, the day-to-day reality is most pressingly concerned with management directives, organisational pressures, staffing issues, financial goals, costs and budgets, and personal issues of performance, pay and promotion. Things like ‘best practice’ corporate governance, corporate citizenship and stakeholder interests can seem at least one step removed from these everyday concerns. The ongoing task for most organisations in both the public and private sectors is to connect the external factors to the internal factors on all of the governance levels which matter — organisational and personal performance measures, strategic and financial planning, and so on. These tensions are illustrated in Diagram 1.[40]

One of the nagging issues in corporate regulation concerns the extent to which directors’ duties extend beyond duties owed to the company and its shareholders. The standard commercial mantra that the business of corporations and their directors is to maximise profits, stock values, financial shareholder returns and ensure business sustainability (because of their primary obligation to act in the best interests of the corporation and its shareholders, rather than to meet wider community interests) might well be right. However, it frames the issue in a particular way and is contingent upon the truth or falsity of some deeper assumptions about the proper relationship between corporations and their communities. Unfortunately, public debate on this issue is usually dominated by stakeholder posturing and spin at the level of mantras about ‘corporate best interests’ and shareholder/stakeholder accountability rather than analysis at any deeper or wider level.

The conventional view is that, wherever there is a conflict between profitability and wider concerns like corporate citizenship, a director looking at the current law would say, ‘I have to act in the best interests of the company and

I can’t sacrifice profitability and financial return for these other things’. Is the law on corporate obligations really as ‘zero-sum’ as that comment suggests? Is it possible that considerations of corporate citizenship might condition directors’ duties or their business judgments in a way which would legally allow stakeholder and wider community interests to be factored into the calculation of corporate and shareholder best interests by directors as part of their legally enforceable duties? That direct linkage now seems unlikely in Australia, except by legislative amendment. In Spies v R,[41] the High Court rejected previous judicial intimations that, in addition to their duties to the company, directors might owe independent duties directly to and enforceable by existing or potential creditors. The High Court cited and implicitly accepted Justice Gummow’s explanation in Re New World Alliance Pty Ltd; Sycotex Pty Ltd v Baseler[42] that the ‘duty’ of directors to consider the interests of creditors in situations of insolvency or near insolvency ‘is merely a restriction on the right of shareholders to ratify breaches of the duty owed to the company’.[43]

Saying that directors owe no direct duty beyond the company and its shareholders to creditors certainly precludes that they might owe this direct duty to non-creditors. However, it is not the same as saying that directors are precluded by their duties from factoring the interests of creditors and non-creditors into their decision-making in some way. Nor does it settle whether such assessments can ever form part of an assessment of what is in the best interests of the corporation and its shareholders under the current law. Nor does it settle what reform of the law should impose upon corporations and their officers as wider duties, if any.

There are critical regulatory, management and jurisprudential issues here. Why would any director, manager, or adviser whose remuneration or performance is assessed according to short-term timelines and financial measures alone have any incentive beyond social altruism or career suicide to pay any meaningful consideration to medium-term social consequences and non-financial measures like social audits and ethical investment principles? To use accounting jargon, what is the incentive here for the corporation generally or the corporate agent in particular to internalise the external costs of a course of action? How do you institutionalise and operationalise wider community interests and human rights concerns in corporate decision-making? There is much to be said for regulation which reflects the reality of transnational operations of multinational corporations and their potential for breaches of human rights and socio-environmental standards, and which also strikes at high points of both institutional leverage (eg, imposition of corporate reporting and disclosure obligations) and personal leverage (eg, imposition of personal liability) in corporations.[44] If there should be corporate reform to enhance the connection between corporate obligations and social responsibility, should that rely on changes in government policy (eg, including social audits and other non-financial measures in criteria for awarding government tenders), self-regulation (eg, industry standards and codes), or legislation (eg, the Corporate Code of Conduct Bill 2000 [2002] (Cth))?

An Australian-based partner in United States law firm Skadden Arps Slate Meagher & Flom, Robert Hinkley, suggested in April 2000 that five basic obligations of citizenship should be included in amendments to the duties of directors under corporate law, so that their primary profit-making enterprise for shareholders would not be ‘at the expense of the environment, human rights, the public safety, the communities in which the corporation conducts its operations or the dignity of its employees’.[45] His rationale for this suggestion combines the business orientation of a commercial lawyer with a realistic appraisal of regulatory, business and individual dynamics:

Corporations … exist only because laws have been enacted that provide for their creation and give them a licence to operate. …

… The corporate law establishes rules for the structure and operation of corporations. The keystone of this structure is the duty of directors to preserve and enhance shareholder value — to make money. Under this structure, the objective of stockholders — making money — becomes the duty of directors which, in turn, becomes the marching orders for the corporation’s officers, managers and other employees. … Most corporate decisions are made by people who have little incentive to promote corporate citizenship or social responsibility (which in some measure requires corporate sacrifice) unless such promotion also can be shown to improve profitability … Nothing in the system encourages (let alone requires) corporations to be socially responsible or to contribute, cooperate or sacrifice for the benefit of the community or the common good (that is, be a good citizen).

… The duty of directors to make money drives all corporate actions. This makes it the point of highest leverage. Corporations will take on the obligations of citizenship only when the duty to make money becomes balanced by something that simulates the human conscience. … It is time to amend corporate law to encourage corporations to be good citizens as well as make money.[46]

Whatever anyone thinks about whether corporations should be legally compelled to meet wider social obligations, Professor Bob Baxt is clearly correct in this assessment:

Many people believe directors of large corporations, including banks, insurance companies, telecommunications companies etc, should have regard to a broader set of community obligations. However, if that is the way society wants to regulate such companies (I do not agree this is the best way of dealing with the problems that may face the community, but it is an option that is favoured by some), then legislation governing the duties of the directors of such companies should be clarified … If directors are expected to run the activities of their companies with the interests of the community at the forefront of their obligations, then they must have adequate protection in the law (and from the courts), that should shareholders feel they are not receiving the same level of dividends they had been accustomed to, the directors will not be in breach of those duties.[47]

In short, if we are serious about institutionalising wider community interests within corporate decision-making, we need to recognise a few things. There is not necessarily a zero-sum correlation between shareholder interests and wider community interests, such that one inevitably detracts from the other. It is unacceptable to leave the law in a state where such assessments might or might not be implicit within directors’ duties and business judgment defences. In other words, as Baxt argues, directors’ legal obligations should be legislated clearly one way or the other. Chanting the mantra of ‘what is in the best interests of corporations and their shareholders’ simply begs the question of what is in their best interests. What does this mean, for example, in the context of directors of government business enterprises who must act in the best interests of their corporations and shareholders but whose shareholders are shareholding ministers who represent wider community interests? Moreover, the interests of shareholders are significantly but not exclusively financial, leading to deeper problems in institutionalising both financial and social measures in decision-making, as part of the exercise of internalising within the corporation the external costs of corporate action for the wider community. Society cannot legislate one way or the other on the content of directors’ duties without first settling the extent to which corporations must not only comply with legal regulation in a minimalist sense but should also meet social obligations because of society’s creation of market and economic conditions for their flourishing (ie, the ‘quid pro quo’ argument). As Hinkley indicates, directors’ and officers’ legal obligations are probably the highest point of leverage for implementing change of this kind.

Much corporate and regulatory thinking is predominantly locked in a zero-sum conflict between shareholder and stakeholder theories of corporate responsibility, on one hand, and contractarian and communitarian theories, on the other. According to the ‘quid pro quo’ argument, corporations operate in communities. They receive the benefit of tax concessions and incentives from governments. They receive the benefit of market regulation. Consequently, on one view, there is a price to pay for the status and privilege of corporate existence, and the quid pro quo for this is that corporations and directors cannot make financial decisions in a social vacuum. According to ‘triple bottom line’ thinking, corporations should focus holistically on the economic, social and environmental dimensions and implications of their business and not simply on the ‘single bottom line’ of financial considerations, profits, business costs, and share values and dividends. Yet that alternative conception also assumes much about how we should view and regulate corporations.

Of course, there are many complexities here as well as theoretical tensions between what Professor Stephen Bottomley has described as the alternative concession-based, contract-based and constitutional views of corporations in society.[48] Bottomley proposes a middle ground, advocating a theory of ‘corporate constitutionalism’ in which ‘a corporation is an institution which, via its constitution, mediates public and private interests and values’, so that ‘corporate regulation should be based on both state and corporate inputs’. This view denies the absolutism of the ‘corporations exist solely to maximise shareholder value’ school and the ‘corporations have an absolute obligation to the communities which confer status, privilege and benefits on them’ school.[49] As he explains:

The theory of corporate constitutionalism begins with the proposition that corporations are more than just artificially created legal institutions (contrary to the suggestions of concession theory) and they are more than just economic institutions (contrary to the argument of contract-based theories). Corporations have both of these dimensions, but they are also social enterprises and they are polities in their own right. Beginning with this proposition, corporate constitutionalism argues that the means by which corporations are governed and by which they govern should be constituted by state and corporate inputs.[50]

So, rather than viewing corporations simplistically and one-dimensionally as being pro-profits (often at the expense of the community) or alternatively pro-citizenship (even at the expense of shareholder returns), this more complex dualist view offers a more sophisticated perspective which is arguably closer to corporate and socioeconomic reality. Of course, it is simply a starting point for reframing corporate thinking, regulation and practice.

Can anybody nominate one director or business professional who, in their public statements, is not in favour of business ethics, good corporate governance, corporate citizenship, respect for human rights and corporate contributions to the fabric of society? I doubt it. Those things are part of the public rhetoric and often the private concerns of people in business. What we are really talking about here is the problem which arises through ineffective models of thinking when it comes to so-called ‘real life’ commercial decision-making.

Indeed, while the dynamics of corporations and the market need separate consideration from the perspective of business ethics on institutional and structural levels, too often the relevance of business ethics or even corporate citizenship is difficult to grasp on a personal level. Mention something like ‘corporate citizenship’ to many corporate lawyers and they will metaphorically roll their eyes before shrugging their shoulders at the idea that such notions can offer meaningful practical guidance at the necessary level of detail for directors about fulfilling their statutory directors’ duties under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). Mention the notion of the ‘triple bottom line’ to boards and managers who act in line management positions and they will collectively shrug their shoulders at the idea that this has too much connection with the real and everyday ‘bottom line’ of corporate profitability, institutional and personal performance and financial shareholder returns. This marginalisation, compartmentalisation and de-intellectualisation of corporate decision-making is too often defended on the anti-theoretical basis that contrary calls to incorporate wider interests are rhetorical at best and either commercially naive or quaintly academic at worst. The narrowness of mindsets which can occur in calculations of corporate interests is not always somebody’s fault. Indeed, as Andrew Stark once remarked:

I suspect that the field of business ethics is largely irrelevant for most managers. It’s not that managers dislike the idea of doing the right thing ... but real-world competitive and institutional pressures lead even well-intentioned managers astray.[51]

Nor should the introduction of higher-level ethical and governance concerns necessarily complicate what is otherwise supposed to be a straightforward exercise of acting in a company’s best interests by acting in the best interests of its shareholders. As ethicist Simon Longstaff asks:

How many boards have a formal process requiring senior management to consider and report on the ethical implications of proposals included in board papers? How many directors can name the core values and principles of companies they govern, and agree to abide by them when making decisions? … The truth is that life does not become more complicated because of ethical reflection. Ethics reveals the complication that is already there and that largely goes unnoticed — until it is too late. Imagine how much better life would be if there had been even a little more ethical reflection in the boardrooms of HIH, One.Tel, Arthur Andersen, Enron, WorldCom.[52]

Unthinkingly adopting a non-holistic form of economic analysis as the default framework for corporate regulation and assuming the value-neutrality of market forces serves to reinforce some interests at the expense of others, and also straitjackets our thinking in ways which might not reflect a deeper reality. As Professor Max Charlesworth wrote about business and markets in the early 1990s, in terms which still resonate in the era of Enron and CLERP 9:

In the area of business and commerce, while there is a growing awareness of the importance of ethics, the myth that business is business and that it is an inherently self-regulating machine, and as amoral as any other mechanical system, retains a great deal of its force. …

The central myth in the sub-culture of business is, of course, ‘the market’. The notion of the market is conceived in mechanistic terms: the market is self-regulating and ethical considerations are as irrelevant to its functioning as they are to any other mechanical system such as a watch or a motor car. At the same time there is a happy coincidence between the operations of the market and general happiness … If one takes an anthropological approach to the sub-culture of business, one sees that ‘the market’ is an idealisation, a concept abstracted from a complex tissue of social and cultural and legal and other factors without which it would have no meaning.

The market operates within some kind of state welfare or service system: that is where the state is expected to provide some degree of basic services, or ‘public goods’, such as health, education, law and order, police, etc, and some kind of ‘safety net’ services for the poor, the unemployed, the aged, the disabled, the ill, etc. People may differ over the amount or degree of the services and welfare the state is expected to provide, but no one in any advanced industrial society seriously questions that there should be some such services … What we have in reality then is a state subsidised and state supported and regulated market economy. The very existence of the market depends, in fact, upon continual state intervention.

… While there is a place for the kind of business ethics that deal with concrete aspects of business practice — truth in advertising, fair trading, duties to shareholders, obligations to the environment — there is also a need for a more broadly conceived business ethics which reflect upon the business system itself and upon the broader social and cultural and legal contexts within which business operates and from which it derives its meaning.[53]

Here, the supposed neutrality of the market, enshrined in the common assumptions of ‘competitive neutrality’ and ‘level playing fields’, is exposed in the ways outlined by Professor Charlesworth and in other ways too. Many corporate and business organisations benefit from non-neutral features of the market and the regulatory environment such as subsidies, incentives and regulatory advantages. The market itself is responsive to public interests and expectations as well as shifts in consumer goodwill. The market both shapes and reflects the different dimensions of capital represented in the ideas of economic capital, social capital, human capital and political capital. It consists of interdependent relationships between governments, regulators, companies, shareholders, stakeholders and communities as market participants.

Professor Razeen Sappideen crystallises the competing theories of corporate responsibility and its social and regulatory dimensions as follows:

There has been ongoing discussion concerning the role of markets, governmental regulation, and business ethics. At one end of the spectrum is the view of neo-classical economists, epitomised in Milton Friedman's famous statement that the sole responsibility of business is to maximise its profits subject to the constraints of the law. At the other end is the Marxist view of State ownership of the means of production. In between are various shades of what is known as the stakeholder view, which sees the role of business (and in this context, the role of the large corporation) as serving the needs of society and as deriving its legitimacy from the serving of such needs. The latter view generally recognises that corporations owe obligations not only to shareholders, but also to other constituencies such as employees, managers, and consumers and, in certain situations, to the general public. More recently, the need for ethics in business has again become a key topic for discussion. Ethical business practice requires that corporate management observe more than the dictates of the law, or the signals of the marketplace, and do that which is preferably both right and beneficial to society.[54]

Professor Sappideen ‘focuses on the interdependence of business ethics, economics and law at the point of their interface’, highlighting ‘the presence of a symbiotic relationship between these three strands, strategically interwoven, where each is dependent on the other for its sphere of operation’.[55] Again, the idea of interdependent interests is critical. Many ‘single bottom line’ proponents under-emphasise the interdependence, for example, between corporate, shareholder, stakeholder and community interests, while many ‘triple bottom line’ advocates overemphasise the symbiotic connection between social, economic and environmental concerns for business.

So, is the relationship between corporate benefit and community benefit not really linear but rather, continuous and cyclical? If Eva Cox is right, social capital and human capital are not only as important as financial capital, but social well-being is a precondition for financial capital and economic prosperity to flourish.[56] Similarly, is profitability an outcome of corporate performance which is predicated on corporate responses to regulatory, economic, social and environmental dynamics rather than a business pursuit in its own right? Global and social trends and conditions affect the conditions for financial profitability in integral rather than marginal ways. Financial profitability requires the right community conditions, regulatory environment, politico-legal system and economic climate. Shareholders demand financial viability and profitability, and citizens expect economic prosperity to flow though to social benefits. Shareholders are not just shareholders but investors, consumers and members of families and communities. Informed shareholders are unlikely to accept that ethical and community concerns are always marginal or outweighed by economic considerations, that framing economic and non-economic considerations as competitive rather than complementary considerations is always appropriate, or that calculations of shareholder interests in purely financial terms fully captures the multi-layered notions of ‘the best interests of the corporation’ and ‘the best interests of the shareholders’. This interconnectedness means that saying that ‘good business ethics and good corporate citizenship are simply good business’, which simply treats these things as means to a business end rather than worthwhile for their own sake and relevant to that business end, is too reductionist in its thinking.

Politicians, business associations and community groups variously promote the idea that ‘no corporation is an island’, whether that idea is framed in terms of Prime Minister John Howard’s notion of a ‘social coalition’ or whether that idea lives in the minds of ‘[c]orporate leaders who are becoming more aware of international business moves to promote a ‘civil society’ — ensuring human rights and environmental protection’.[57] Sustained shareholder value is harmed by anything which hampers the corporation’s public reputation, business reputation, consumer goodwill, community support or capacity to influence public affairs. That harm to shareholder investments is not clearly avoided by compartmentalised calculations of corporate profitability and financial returns to shareholders which ignore or marginalise these interconnected concerns. In turn, this damage to a corporation’s political capital, public capital and consumer capital flows through to the corporation’s financial capital and reduces the corporation’s collective will, capacity and resources for contributing to the community in ways beyond supply of its products and services. And so the cycle continues.

None of this denies or undervalues the importance and complexity of corporate and shareholder calculations of their best interests. None of it denies the need to demonstrate how and why the interests of non-shareholders count. None of it makes simple the task of recognising and then weighing the economic and non-economic considerations which relate to corporate interests in combination with profitability, dividends and financial returns. None of it suggests that directors, corporate officers and shareholders will be easily persuaded that their corporation should devote resources and personnel to matters beyond the minimum legal and regulatory necessities and at considerable expense, unless that is related to economically relevant consequences for the corporation in the short or long term. None of it means that directors and shareholders are faced only with a choice to forego tangible profits for the sake of intangible social benefits.[58] It might mean that some corporate and shareholder conceptions of the components of the corporation’s best interests need reframing and even broadening.

Corporate Australia has failed to defend itself against the assault by the stakeholder lobby. … During the past decade, the corporation, particularly the Anglo-American variety, has been subjected to a sustained attack by the stakeholder lobby. This movement’s aim is not to destroy corporations but to regulate and guide them away from the wishes of shareholders. This movement acts not through the marketplace or necessarily through the formal regulatory process, but through public opinion. The movement vigorously promotes a vision of systemic corporate failure — on accountability, governance, performance, contribution to society, treatment of workers and impacts on the environment.

-- Mike Nahan, Executive Director of the Institute of Public Affairs.[59]

As a possible outcome of respecting property rights and yet being concerned about economic justice, one might consider the treatment of workers as a moral issue and thus refuse to invest in a company or buy its products. The same can be done in response to environmental concerns and other social issues. In this way, the social value that is upheld provides a market incentive for corporations to act responsibly.

I would argue that this is a much more ethical way of applying social pressure to an irresponsible company than mandating by law that they comply with certain regulations. Granted, the fear that the consumer won’t respond to these abuses is warranted. However, people are rarely aware of how regulations that are intended to compensate for individual virtue, in effect, worsen the economy, contribute to the causes of corruption, and do little to foster the social virtues that are necessary for a just social order.

-- Reverend Robert Sirico.[60]

Much of this discussion occurs within an ideological map which positions contractarian shareholder-focused corporate models, at one extreme, and communitarian stakeholder-focused corporate models, at the other.[61] Simon Longstaff, for example, questions such underlying assumptions:

I’ve lost count of the number of times I have heard it proclaimed that the principal duty of directors is to ‘maximise returns to shareholders’. Well, is this really so? Who says so? Why? More important still, if such a duty does exist, then should it?

In a similar vein, it is often asserted that company directors have a duty to ‘act in the interests of all stakeholders’. Once again we might ask: ‘What makes a stakeholder a stakeholder in the first place? Why should company directors do anything for non-shareholders at all? What happens when one stakeholder’s interests are at odds with another [such as those of shareholders], which they often are?’[62]

Thus, positing a linear or bi-polar relation between two notional ‘shareholder’ and ‘stakeholder’ extremes is not the only way to view models of corporate responsibility. Nevertheless, focusing on broad differences between ‘shareholder’ and ‘stakeholder’ perspectives has some analytical use.

The shareholder view has strengths and weaknesses. It makes collective business enterprise possible. It recognises the importance of generating wealth for individuals and society ‘through the collective investment by individuals in a common enterprise’.[63] It makes a shareholder’s interest an easily transferable and exchangeable commodity. It emphasises the responsibility of corporate managers, officers and advisers to make prudent financial decisions and investments with other people’s money. It respects the different interests, needs and expertise of owners and managers. It promotes direct accountability to those with direct stakes in the corporation. It recognises that communities benefit overall if corporate benefits for the community (eg, employment, wealth, new discoveries, philanthropy and sponsorship) exceed the externalised costs of corporate profitability for the community (eg, environmental damage). It also recognises that corporations are organisations which promote the social goods of free association, enterprise, wealth creation, individual empowerment, private ownership, individual financial security and ‘dissemination of ideas and the distribution of goods’ - all of which are important in a civil society.[64] On the other hand, in practice it gives greater priority to shareholder interests and profits than to ‘moral norms’ and social needs.[65] It also exerts a gravitational force which favours short-term interests of current shareholders over long-term interests of both ‘inner circle’ stakeholders (eg, employees, customers and creditors) and ‘outer circle’ stakeholders (eg, regulators and the community), especially if performances measures and investment decisions are all focused on changes in relatively short time-frames.

At the same time, Australian and international developments in ‘triple bottom line’ corporate governance such as the global Dow Jones Sustainability Index (‘DJSI’), the Age/Sydney Morning Herald Good Reputation Index (‘GRI’),[66]

ethical investment fund guidelines, and the appointment of investment managers to advise large superannuation funds on environmental, social and corporate governance all point towards a blurring or integration of shareholder and stakeholder concerns. For example, Westpac has instituted a Social Responsibility Committee at board level, and recently became the first Australian and fifth global financial institution to report against new United Nations-sponsored socioeconomic and environmental indicators.[67] Westpac also publicly declares that it supports and complies with Just Business, Amnesty International’s human rights framework developed for Australian companies.[68] The law now requires directors’ annual reports to explain details of corporate compliance with relevant environmental regulation,[69] and product disclosure statements for investment products concerning superannuation, managed funds and life insurance must include information about ‘the extent to which labour standards or environmental, social or ethical considerations are taken into account in the selection, retention or realisation of the investment’.[70]

In the public sector, ‘triple bottom line’ concerns are already being integrated with organisational responsibilities. For example, the corporate plan for federal government business enterprises must include reference to ‘non-financial performance measures’ and ‘community service obligations’ as well as financial measures,[71] while chief executives of federal agencies must conduct agency affairs in ways which promote ‘efficient, effective and ethical use’ of public resources.[72]

Might this reflect a wider trend towards abandoning the old mentality which positions profitability and corporate citizenship often in oppositional terms, and adopting a new mentality in which social ends and better measurement of them become part of the market incentives for corporate social responsibility? Concerns about directors somehow compromising their primary duties to shareholders or sacrificing profits, stock value and shareholder returns if too much is done by a company to become a ‘triple bottom line’ corporation tend to fall away when precise non-economic performance indicators (eg, employee satisfaction, corporate ethical reputation, social impact studies, community service obligations etc) become accepted corporate and individual performance benchmarks as a matter of law and self-governance. After all, compliance with anti-pollution and workplace safety laws to prevent harm to employees and the environment unquestionably increases the costs of business but nobody seriously frames this in terms of unjustified detraction from the financial bottom line or something which compromises the primary directive to satisfy shareholder interests.

Similarly, on its own, the stakeholder view has strengths and weaknesses. It reflects the more complex reality that corporations have ‘multiple relationships’ internally and externally, with many individuals and groups being affected by the corporation’s actions and decisions.[73] It recognises more fully both the connection between shareholder and stakeholder interests and how corporations respond to them in multiple ways. Managers therefore can understand more completely how their financial decisions are not made in a socioeconomic vacuum and are part of ‘a larger social whole’.[74] It suggests an alternative philosophical basis for corporate existence, in terms beyond a simple compact between companies and their shareholders. On the other hand, in some forms it can insufficiently recognise that the interests of shareholders and stakeholders are qualitatively different in many ways. It can compromise or sacrifice the interests of those who run or own the corporation, and who hence have the most direct individual stake in it, in terms of investment, capital and ownership, for the sake of ‘some other social good’.[75] It does not offer any self-evident or easy way of ‘adjudicating the competing demands of various groups’ of shareholders and stakeholders in terms which can be sheeted home to directors, officers and other corporate decision-makers and advisers in terms of specific guidance.[76]

Perhaps it is even time to reformulate the classic proposition that corporate directors and officers must act primarily in the best interests of the corporation and its shareholders. Developments such as the emergence of the ‘sustainability investor’ signal new ways of configuring it. According to Mills, for example, corporate sustainability might be described as a business approach which creates and sustains long-term shareholder value by both embracing opportunities and managing risks derived from economic, environmental and social factors.[77] Taking another example cited by Mills, Shell reportedly now views its contribution to sustainability coming from the value-adding contribution which it makes to a stable socioeconomic system through pursuit of its business values to attract and develop capital and talent.[78] This idea that business sustainability rests fundamentally on a stable underlying socioeconomic system mirrors the recognition by social commentators such as Eva Cox that social capital is a precondition for economic capital and business growth, rather than the other way around, just as a stable politico-legal system is a precondition for business certainty and confidence. These are important developments in shifting business and regulatory mindsets to connect commercial reality to an underlying regulatory, economic, social and environmental framework. All of this supports the more expansive ways of framing governance outlined earlier in this article.

The compartmentalisation of corporate decision-making which occurs in reductionist approaches to ‘the bottom line’ in assessments of corporate and shareholder interests is most exposed in those hard cases where proper attention to ‘the best interests’ of the corporation and its shareholders requires decision-making which is not framed in purely financial terms of dividends and stock values even if it is otherwise properly shareholder-focused. Everybody worries most about wider concerns like business ethics, regulatory compliance, corporate governance and corporate citizenship when corporate behaviour or inaction results in an economic, social, legal, or public relations disaster like a mine or gas explosion, the Exxon Valdez environmental oil spill, or the next Enron, WorldCom, HIH, or One.Tel. However, those wider concerns are always present and always affect good corporate decision-making.

It is true that this wider conception and integration of corporate and shareholder best interests must itself be viewed multi-dimensionally. Some directors of corporations will agree with the wider conception of corporate and shareholder interests but also insist that anything beyond minimum regulatory compliance, minimum incorporation of industry standards, minimum adoption of ‘best practice’ corporate governance standards, and minimum but significant community involvement runs the risk of detracting too much from the (single/financial) bottom line. Equally, who could accept that guidance for any of these decisions adequately comes from sweeping guidelines like ‘the bottom line is the only line’, ‘our business is making money’, ‘our primary responsibility is to shareholders’, ‘ethics is good business’, ‘private corporations have public responsibilities’, or even ‘the triple bottom line is the new reality’? What is in question here is the extent to which unnecessarily compartmentalised thinking and mono-dimensional conceptions of a corporation’s ‘best interests’ really caricature and cloak the complexity of ‘real life’ decision-making factors operating on those at the corporate coal-face, whether they are conscious of them or not.

What are the elements of community-sensitive corporate regulation and promotion of corporate citizenship?[79] Might it envisage government regulation to require all corporations and organisations to spend a minimum percentage of their profit on internal training and education as well as external community service and pro-bono work? Would it extend to awarding government tenders on criteria which tie successful tendering to a nominated minimum percentage of key decision-makers in a tendering organisation coming from women or minority groups promoted through affirmative action, or by reference to other rights-enhancing criteria beyond price and capacity to deliver results, such as social audits as well as accountability and compliance mechanisms for citizens to seek redress from corporations in the private sector who deliver public services on behalf of government under outsourcing arrangements?[80] Would it encompass quality accreditation according to criteria which include compliance with equal opportunity measures and community support? Might it even embrace national prosperity measures which include social indicators as well as economic ones in any formally recognised assessment of a nation’s prosperity? Might international trade agreements be predicated upon the record of human rights compliance by countries and corporations alike? Could governments assist through laws which go beyond simply regulating abuses like misuse of market power by dominant commercial parties (like part IV of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)) into areas of commercial fairness and reasonableness between parties (as parts V and IVA of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) increasingly seem to do)? Might powerful governments and global institutions adopt policies against financial support for projects ‘that knowingly involve encroachment on traditional territories being occupied by tribal people, unless adequate safeguards are provided’?[81]

On some wider levels, of course, all of this reflects what has been said before (and better) by others about ‘the interdependence of business ethics, economics, and law at the point of their interface’.[82] Indeed, the broad division between the two opposing camps is stark:

A threshold issue to be considered is the relationship of business and society and, more particularly, whether corporate behaviour should conform to the moral norms of society generally … The amoral view, epitomised in the views of Milton Friedman, dominated the thinking of the western world until as recently as the 1960s, making a brief comeback in the 1980s. It is founded on the principles of self-interest, the free market, profit maximisation, and the highest return to stockholders, and espouses a form of individualistic capitalism where government plays a minimalist role, protecting property rights and encouraging the pursuit of profit maximisation with a view to ensuring the greatest prosperity. Its fundamental tenet, that economic relations should be based entirely on the exclusive pursuit of self-interest, contrasts with the requirement in most ethical theories that the interests of those affected by one’s decisions should be taken into account.

By contrast, the moral unity view takes into account the interests of employees, customers and society, and emphasises co-operation, interpersonal harmony, and the interdependence of the individual and community. [83]

As is now apparent, some of these notions — for example, the freedom and neutrality of market forces, and the correctness of a minimalist approach to governmental regulation — are controversial and need justification. Some of them (eg, returns to shareholders and profit-maximising) can be viewed one-dimensionally in financial and self-interested terms or multi-dimensionally in wider and interconnected terms.

Such ‘big picture’ dynamics also have cross-national and cross-disciplinary manifestations. For example, the concern of Japanese communitarian capitalism for the three intertwined strands of the common good — ie, the pursuit of happiness and prosperity, the concern for justice and fairness, and the affirmation and importance of community[84] — has some correlation to the three intertwined strands of the ‘triple bottom line’ for companies, in terms of profits, the environment, and the community, at least in terms of a multi-layered approach to corporate interests. This is similar to the claim of philosophers that one’s own self-interests and preferences, properly considered, can embrace a variety of interests and be both self-actualising and other-centred, including an individual desire to promote justice and prosperity for one’s self and others.[85] In that light, who can deny that the impact of corporate conduct on others and a desire to treat those affected by corporate conduct fairly and justly, together with a desire to promote social well-being as well as individual shareholder prosperity, are all part of a much more complex and multi-layered framework within which directors and shareholders alike must conceive of the best interests of a corporation and its shareholders? As High Court watchers will tell you, today’s heresy is often tomorrow’s orthodoxy.

The issue of human rights is central to good corporate citizenship and to a healthy bottom line. Many companies find strength in their human rights records; others suffer the consequences of ignoring this vital part of corporate life. Today, human rights is a key performance indicator for corporations all over the world.

-- Mary Robinson, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, launching Business and Human Rights: A Progress Report (2000).[86]

[I]t makes good business sense anyway for executives to take account of the interests of, and work closely with, key stakeholder groups and local communities. … Triple Bottom Line Reporting seeks to elevate fuzzy and subjective concepts and places them alongside objective and measurable reporting of financial outcomes. … [C]ompanies have more than enough on their plates with Single Bottom Line Reporting. … Any practice that interferes with a company’s ability to achieve its financial objectives … is tantamount to ‘killing the goose that lays the golden egg’.

-- Australian Shareholders’ Association.[87]