University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

ROB DAVIS[*]

Over the last 12 months Australian liability insurers have conducted a concerted campaign for tort reform in Australia. This campaign attempts blame for recent premium increases on lawyers, the legal system, and injury victims.

The campaign has provoked a wave of legislation intended to restrict the ability of ordinary citizens to obtain fair compensation for negligently caused injury. This process has been given impetus by the flawed Review of the Law of Negligence (‘Ipp Review’), conducted by the Panel of Eminent Persons (‘Ipp Panel’).

I say flawed for three reasons. First, the Review arose out of the insurers’ public campaign for tort reform, a campaign big on rhetoric but scant on facts. Second, the terms of reference of the Ipp Review were designed so as to deny any analysis of the truth of insurer’s claims about the causes of premium increases. Third, the membership of the Review committee was stacked with persons ideologically committed to tort reform regardless of the true causes for premium increases.

This paper attempts to do what the Ipp Review did not. It critically examines the case that has been argued by the insurance industry for tort reform and finds it empty of substance. The writer concludes that the insurance crisis has provoked ‘tort reform crisis’ in this country. A crisis that will only be averted by a renewed focus on the value of civil rights in Australia and an appreciation that, in this instance, many of these rights have been legislated away to fund the market driven mistakes and excesses of insurers.

Underpinning all the different iterations of the insurer’s tort reform campaign is a myth imported into the Australian psyche from popular culture in the United States (‘US’), namely the meme that the legal system has gone mad. That ‘Santa Claus’ judges have encouraged a culture in which everyone feels there is no injury without blame, and no blame without a claim.

This myth had its geneses in the US in a campaign by right wing ‘think tanks’ (funded mainly by corporate manufacturers and insurers) to react to the expansion of American liberalism in the 1960s and 70s. Liberalism, in this context, refers loosely to the intellectual movement that encouraged the expansion of civil rights, (including consumer and worker rights), and threatened corporate profits.

The local campaign follows the blueprint for industry driven attacks on citizen’s rights refined in the US over two decades ago. As with the US strategy, it has sought to portray injured claimants and their lawyers as greedy, unmeritorious, and vexatious, while portraying the industry and its allies as good corporate citizens and productive taxpayers who are victims of a legal system gone mad.

The campaign, like the US campaign before it, has relied on false assertions about litigation and claims rates mixed with exaggerated (and sometimes entirely bogus) examples about outrageous lawsuits and the increasing litigation.

The goal of the campaign is to confuse the Australian public about the true causes of the current crisis in the insurance industry and, in the process, convince them to surrender valuable legal rights.

The insurance industry’s case for tort reform has evolved over time, subtly shifting emphasis as each wave of their attack was refuted by facts. But each reiteration of the insurer’s campaign has reinforced the same ‘legal system gone mad’, ‘blame and claim’ memes.

An early offensive mounted by the insurers in the current campaign was the claim that Australia is undergoing an explosion in frivolous US style litigation. This claim was quickly accepted and propagated by tabloid journalists, talk show hosts and a host of industry and professional groups keen to accept the claim at face value.

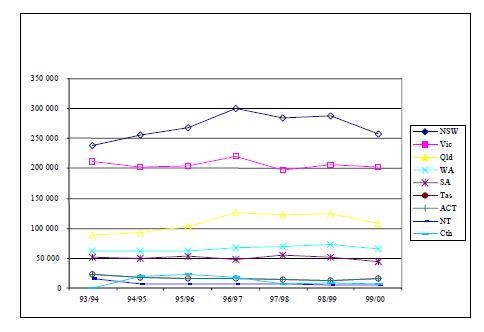

The claim itself is entirely bogus. Australia is not undergoing any litigation explosion at all. On the contrary evidence from the Australian Productivity Commission demonstrates clearly that civil litigation in Australia has declined gradually since 1996–97 (see figure 1).[1]

FIGURE 1: CIVIL ACTIONS COMMENCED IN ALL COURTS OF EACH JURISDICTION

The second tactic of the insurance industry was to claim that as the Productivity Commission’s report aggregated all civil litigation data it therefore masked the real explosion that had occurred, namely in personal injury litigation.

This latter claim also is not supported by evidence of actual court filings from courts around Australia.[2] Court data reveals that increases have occurred in some jurisdictions but that there have been declines in others. Where increases do exist they are explicable by changes in the monetary jurisdiction of courts and, in some cases, legislative attempts at tort reform that forced claimants to issue proceedings earlier than would otherwise have occurred.

Further, over the last decade the Australian population has increased by approximately 10 per cent with an even more rapid growth in the ageing population. This underscores the fact that some increase in litigation is to be expected in any event and that increase, by itself, is indicative of nothing.

In summary, the data reveals no evidence on any sudden or recent increase in personal injury litigation sufficient to justify the massive recent increases in premiums. This conclusion has since been agreed to by a number of informed commentators.[3]

The insurers also assert that Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (‘APRA’) data demonstrates there has been a massive increase in the number of public liability ‘claims’. Commonly they cite the figure that claims increased from 55 000 in 1999 to 88 000 in 2000.[4] Insurers attempt to explain the contradiction between increasing claims numbers and declining litigation trends by claiming that most insurance claims are settled out of court.

In fact there is a much simpler explanation for the discrepancy. The APRA data is grossly unreliable. So unreliable in fact that the insurance actuaries employed to advise the Australian Heads of Treasury, the very same actuaries also used by the Insurance Council of Australia, refused to rely on the data at all.

There is a further reason why the claim is bogus. APRA’s data on claim numbers is not a measure of the rate of claims at all. Gross increases in claims numbers does not say anything about the rate of claims unless it is expressed as a ratio, such as the ratio of claims per policy or claims per A$ 100 000 of premiums. When analysed in this manner the APRA data reveals that the ratio of claims has actually declined since the mid-1990s. Further, a review of claims and policies for the last decade reveals that claims against policies have increased, but at a lower rate than the increase in policy numbers.

The result of this analysis is that the rate of claims has declined, not increased. Notwithstanding this fact, commentators from the insurance industry continue to repeat the misleading assertion that public liability claims have undergone massive increases.

In a further attempt to bolster the argument for tort reform insurers also assert that average claim sizes in all jurisdictions have increased faster than increases in inflation. This claim, like the others referred to above, is also misleading. Comparisons between average claim size and inflation are irrelevant because inflation is a retrospective measure, whereas average claim sizes include both past and future losses.

Average claim size is expected to increase at a rate faster than inflation as the future component of damages awards is calculated on lost wages, cost of medical care and cost of home care based on values existing as at the date of trial. As most of large awards represent future losses this has the effect of leveraging up the future component faster than the past component. Insurers should know this and price their products accordingly.

Another claim made repeatedly by insurers is that the aggregate cost of claims added to administration expenses has increased and now exceeds premium income raised.

The difference between claims cost and premiums is often referred to as the underwriting result. The claim that insurers currently experience a negative underwriting result is intended to reinforce the ‘blame and claim’ meme.

The reality is that Australian liability insurers (like their counterparts in Canada and the US) have traditionally (and willingly) operated with negative underwriting results, relying instead on investment returns for their profits. Indeed, APRA statistics reveal that over the last 20 years Australian general insurers, in aggregate, have never booked a positive underwriting result.[5]

What have recently changed are insurers’ investment returns. These have declined as a result of bear equities markets and low interest rates. This means the income they previously used to book profits, declare dividends, fund mergers and acquisitions and finance massive CEO salaries has evaporated, forcing them to increase premiums to now book positive underwriting results.

Throughout this campaign the insurance industry has constantly attempted to blame the increases in premiums on defects in the tort system. The goal of this campaign has been to extract tort reform from legislators looking for a means to fix the insurance crisis. In other words, premiums have increased because of litigation; ergo reducing litigation will reduce premiums.

Enticing as this proposition appears, it is nonetheless invalid. The incorrect nature of the position has been highlighted in recent weeks with insurers, whose claims have finally come under some media scrutiny, now openly refusing to guarantee that premiums will decline in response to the tort reform.

This belated acknowledgement is supported by a large-scale study on the effects of tort reform on premiums in the US over the last quarter of a century. That study revealed no relationship between tort reform, or even the absence of tort reform, and premiums.[6]

The reality is clear. The current crisis in insurance has nothing to do with litigation or any cultural shift in Australians’ propensity to blame others for injury. As these things are not the cause of the current crisis, then it follows that the current orgy of tort reform embracing Australia is not the solution.

Usually premium cycles are driven by insurance capacity, and this is influenced by economic cycles in equity markets, interest rates, global claims experience and, ultimately, competition.

When earnings are high (soft markets) capital floods into the industry. This influx of capital sparks new entrants and increased competition. When earnings are low (hard markets) capital floods out of the industry into other markets where it remains until it is enticed back by increasing profits.

The profitability of the insurance industry constantly cycles between hard and soft markets. Liability insurance globally has experienced hard markets that bottomed in each of 1966, 1975, 1984, 1992 and now, 2002. The hard markets currently experienced in Australia also exist in Canada, the US, Singapore and the United Kingdom. This cyclical lack of capital has been aggravated globally by the 11 September 2001 tragedy, which is estimated will cost the liability market at least US$40 billion, and locally by the spectacular collapse of HIH/FAI.

Tort reform does not fix market cycles, it merely provides temporary subsidies to paper over the consequences of market inefficiency, corporate incompetence and occasionally outright dishonesty. When the market cycle turns soft the tort subsidies are then consumed underwriting another round of corporate excesses in which all the same mistakes are repeated, albeit from a lower subsidised cost base.

Meanwhile the insurance consumer never sees the benefits of these subsidies and the injury victims progressively have entitlements eroded in a system that becomes increasingly distorted by so called tort reform. Eventually hard markets return, and each time they revisit the industry the same insurers reappear with their hands out pleading for governments to assist them with more ‘tort reform’.

We do have a crisis in insurance, but it is not caused by the things insurers say it is. As bad as this crisis is, it is temporary. The insurance crisis is nothing compared to the crisis our society faces from underwriter driven tort reform. The current round of tort reform has caused enormous and permanent damage to the integrity of Australia’s legal system.

The only solution from these attacks on citizen’s rights is to put them beyond reach of insurers and their proxies. It is time all Australians’ rights are protected by a constitutional charter of civil rights.

[*] B Soc Sc, LLM, LLM (Corp & Com), current National President Australian Plaintiff Lawyers Association; Adjunct Professor with the Centre for Tourism and Leisure Management of the University of Queensland.

[1] Australian Productivity Commission, Australian Productivity Commission Annual Report 2000–2001 (2002), table 9A.1.

[2] Rob Davis, Exploring the Litigation Explosion Myth (2002) APLA Public Position Paper, 8 January 2002. (This paper was tabled at the Senate Economics References Committee inquiry into Public Liability and Professional Indemnity Insurance, 9 July 2002).

[3] Trowbridge Consulting, Public Liability Insurance: Practical Proposals for Reform (2002), Report to the Insurance Issues Working Group of the Heads of Treasuries, 30 May 2002; Helen Jones, Indrani Nadarajah and Kate Tilley, Public Liability Handbook Balancing Risk and Opportunity (2002) 81, ch 4.

[4] To support this figure, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority Annual Reports for years to December 1998–2000 are used.

[5] Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, ‘Underwriting patterns in General Insurance’, APRA Bulletin, June Quarter 1998, 2.

[6] J Robert Hunter and Joanne Doroshow, The Failure of ‘Tort Reform’ to Cut Insurance Prices (1999).

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJl/2002/54.html