University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

GRAEME ORR[*]

In common with other English-speaking jurisdictions, Australia has experienced a long period of political stability. Although disaffection with the major parties has increased over the past 15 years,[1] a two-party system of government seems to be entrenched. But a relatively predictable if not dully oscillating electoral cycle does not guarantee modesty. In common with most democracies, mass electoral politics in contemporary Australia has become untethered from ideology and addicted to an expensive habit of electronic campaigning.

Major party politics is big business. In the financial year encompassing the 1998 federal election (which happened to include an election in the largest State, New South Wales) the conservative parties and the Australian Labor Party (‘ALP’) reported expenditures of $61.5m and $58.3m respectively. It is in this context that the spectre of money controlling electoral politics periodically excites considerable concern and debate. Indeed, internationally, particularly in the United States (‘US’) and the United Kingdom (‘UK’), it is the central issue in election law.

There remains a view that Australia is a pioneer in the implementation and development of electoral reforms. But this view is something of an historical conceit.[2] The secret ballot, universal adult suffrage, compulsory voting, preferential balloting for lower houses and ‘semi-proportional’ representation for upper houses[3] were all significant and admirable reforms. But they are receding landmarks on the path of democratic evolution. Admittedly 1983 witnessed the establishment of an independent and professional federal electoral authority, the Australian Electoral Commission (‘AEC’). But that administrative achievement aside, fighting on the battlefield of parliamentary electoral law settled into an endless skirmish over detail long ago. It is a battle that consumes much legislative time and partisan energy, but generates few new ideas.

The one exception to this stagnant picture has been reform relating to electoral finance and disclosure. Starting in 1981 with seminal reform in New South Wales, public funding and disclosure laws have become fixtures of electoral regulation. However, after a burst of significant reform, it is less easy to discern the principles in today’s debate, and much easier to find evidence of bipartisanship based on the convenience of the major parties.

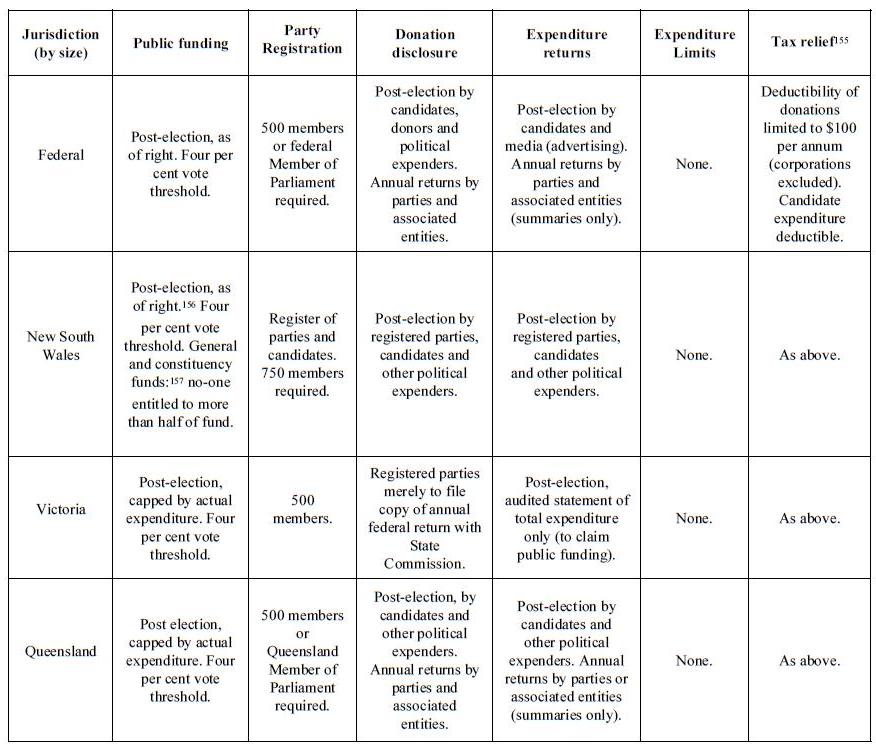

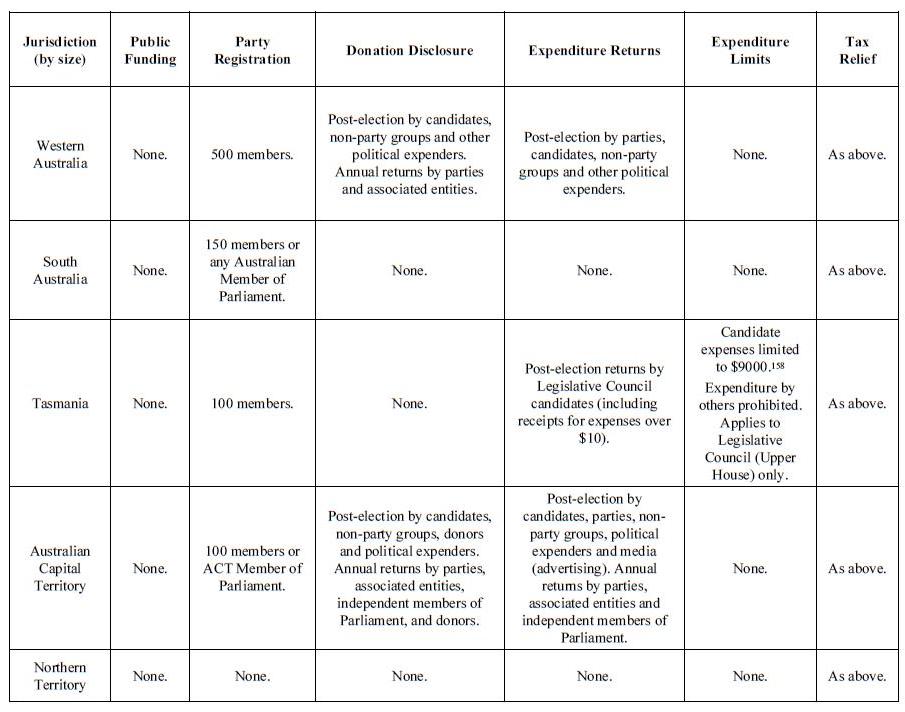

Unsurprisingly, in a federation of six States and two internal Territories, electoral finance laws governing State and Territorial elections are a patchwork of difference and varied development. Since these jurisdictions control local government, the laws governing local elections are even more patchy and underdeveloped.[4] For ease of reference, the key features of each parliamentary jurisdiction are plotted in the appendicised table. At a glance, it will be seen that, as well as the federal regime, four of the States and Territories have public funding regimes, and four – although not the same four – have reasonably well-developed regimes requiring disclosure of donations.[5]

Outside the political elites, funding and disclosure laws have attracted curiously little scrutiny until recent times. Certainly there were occasional voices from the right complaining about public funding.[6] And conversely, there were always dissident voices, often from the left, complaining of loopholes in the disclosure laws.[7] Yet as recently as 1993, a parliamentary library report felt able to conclude ‘that the intent of the funding disclosure legislation is being marginally vitiated by current practices but … this is not a matter for serious public concern (although the situation will have to be continuously monitored)’.[8]

In recent years, however, the ‘policing’ agency (the AEC), along with sections of the press, have anxiously signalled such concern. Indeed, the AEC has begun to express alarm:

[I]f the disclosure provisions in the Electoral Act are to deliver transparency in the financial relationships of political parties, candidates and others associated with them, then a comprehensive review of the legislation and principles underpinning the legislation is required.[9]

Academic researchers, too, are beginning to lay the groundwork for informed critique. For some time, work in the field had largely been left to an economist, Ernest Chaples.[10] Since 2000, however, diverse works have appeared detailing the historical roots and evolution of the law in Australia,[11] critiquing the disclosure regime and calling for legislative limitations on political donations.[12]

A major research report into corporate donations has also been published by Ramsay et al.[13]

The field has not, however, been the subject of much litigation.[14] In part this reflects a cooperative, rather than zealous, approach to enforcement and reporting by the AEC. It also reflects the difficulties involved in proving intent in those instances of missing or misleading returns that are detected by random audits. For example, no donors have been fined for such breaches since the mid-1990s.[15]

Nor, with the occasional exception such as Ramsay et al, have trends in donations and expenditure received sustained empirical attention. Yet media investigators and researchers alike have voiced complaints about the presentation and transparency of some of the data produced in disclosure reports. For example, party and associated entity annual returns only become available on 1 February each year – seven months after the end of the reporting year. Further, these returns do not require donations and other receipts to be separately identified, although some parties choose to do so. The complexity of the law is a further hurdle to interested onlookers. This complexity is evidenced by its bulk. For example, the federal statutory provisions on funding and disclosure extend over 55 pages.[16]

This paper maps out the essential federal provisions governing the whole field of campaign finance regulation. It also canvasses, where pertinent or noteworthy, any differences in State law. Whilst federal Parliament has very limited power over State elections, in practical terms its influence over State politics is significant when it comes to campaign finance. First, federal regulation provides the central platform for debates over the shape of regulatory norms in the field: it is both the driver, and the most important source of inspiration.[17] Second, even though federal and State elections are not held at the same time,[18] the federal system of disclosure of donations serves as a kind of catch-all. This is because most parties’ State and Territory branches register federally. Further, these branches operate as single financial and campaign units, regardless of whether they are contesting State or federal elections. The reverse, however, is not necessarily the case. Parties whose ongoing operations are confined to one State may only be required to make disclosure at State level (if at all), even if they have a ‘shell’ federal organisation.[19]

The paper falls into two parts. First is a description of the current legal position. Then follows a discussion of areas of concern and potential reform. Tham has argued that the regulation of political donations has been ‘ineffectual by design’.[20] Whether it has been by design or neglect, the general consensus of those without a vested interest is that the laws need significant tightening and constant vigilance. I highlight three areas. First, the disclosure regime is a leaky sieve, and in some respects (for example, the sale of political access) it is misdirected. Secondly, it is clear that the public funding regime as instituted in Australia has not served its founders’ purposes. It needs to be reinforced by greater public funding and, more importantly, the introduction of expenditure limits. Thirdly, the general absence of any disclosure requirements, let alone expenditure limits, in local government elections is indefensible.

I end on a cautionary note, questioning the conditions in which a funding and disclosure regime could become so ineffectual as to be worse than none at all. But I do not wish this caution to be interpreted by public choice theorists, or post-modernists, as a call to inaction. Disparities in wealth, and their exploitation to distort the public sphere, will always be with us. The fluid power that money has over politics will therefore always pose sharp regulatory issues. We remain equally in danger of underestimating the corrupting influence of the money spectre in politics as we are of becoming excessively paranoid about its apparition.

This paper does not attempt to chronicle the history of the law’s evolution in Australia: Cass and Burrows have done this admirably.[21] However, readers ought be aware of the key elements of what came before. Prior to the 1980s, the Australian approach to electoral finance was, by default, largely laissez faire. Apart from some residual laws from the Victorian era, the statutory schemes and attitudes were British, indeed common lawyerly, in their outlook. It was a case of trusting – or rather hoping – that political decency would prevail.

Cass and Burrows make a case that, early expenditure limits aside, the essential themes of the contemporary regulatory regime were present in the post-Federation regime of regulation.[22] This is true in the sense that the principle of post-election disclosure of information relating to campaign finance is not a new concept. Further, by drawing attention to the fact that expenditure restrictions at the turn of the 20th century were considered not just compatible with, but necessary to buttress electoral democracy, Cass and Burrows also challenge those who hold the libertarian view that unregulated electoral expenditure is essential to liberal democracy.[23]

However, in other respects, I would argue that the contemporary Australian regime of public funding, allied to requirements of broad disclosure of donations (and not merely candidate expenditures), has no indigenous antecedent in either scope or ambition. The strengths and weaknesses of the model that hatched in the 1980s and spread through Australia in the 1990s, can only be understood on its own terms.

Nonetheless, there are two historical observations that need highlighting. The first is that for most of the 20th century, federal electoral law ostensibly imposed strict limitations on candidate expenses. The second is that these limitations were tied to a system that required candidates, as well as any groups that had expended money in the interest of any party or candidate, to make post-election returns of expenditure.[24] The system was modeled on 19th century UK provisions whose genesis lay in the crackdown on corruption in the form of vote-buying by individual politicians. However, the more modern concern is not with politicians buying votes. Quite the reverse: the real problem in the 20th century has been with businesses and sectional groups buying influence over politicians.

These genetic limitations of misdirected purpose aside, the 19th century system was fatally flawed for two practical reasons. First, the expenditure limit was imposed only on promotions of individual candidatures. This ignored the rise of political parties as ‘brand labels’, the Presidentialisation of politics and the evolution of the mass media campaign. These involve saturation advertising tightly controlled by central campaign offices rather than candidates.[25] As UK case law revealed, all these factors rendered nugatory a system restricted to limiting constituency campaign expenditure.[26]

Second, as the purpose of the laws was outflanked, the laws themselves fell into disrepair, if not disrepute. The original expenditure limits of $500 for Senate candidates (who campaign in multi-member State-wide electorates) and $200 for House of Representatives candidates (who campaign in single-member constituencies) were revised just once in almost 80 years.[27] This was in 1946, when they were increased to $1000 and $500 respectively.[28] The extent to which these limits were honoured, at least in their early days, is unclear.[29] But when more stringent limits, which had lain idle on the statute books of Tasmania, were taken seriously by that State’s Supreme Court in 1979, a political kerfluffle ensued. Rather than leading to a crackdown on the equivalent federal provisions, the kerfluffle merely led to the limits being abandoned.

The Tasmanian cases involved petitions against several State members from the same multi-member constituency who had admitted to the illegal practice of incurring excess expenditure on their candidatures.[30] The Supreme Court of Tasmania, sitting in effect as a Court of Disputed Returns, declared the poll void and ordered a re-election. The political caste across Australia was thrown into apoplexy: excess expenditure had, after all, become commonplace. Within a year, the conservative Federal Government seized the momentum and repealed federal expenditure limits.[31] This ushered in a period of total laissez faire in federal electoral finance law.

Undaunted, the Tasmanian Supreme Court went further and strictly interpreted the State law so as to outlaw third party expenditure – including any expenditure by political parties in promoting their ‘teams’ – unless the expenditure fitted within the candidate’s allowance.[32] But this purgation lasted just one election as the incoming Tasmanian Government watered down the State expenditure restrictions in 1985. They now only apply to the State’s ‘gentlemanly’ Upper House and, even there, the threat of judicial unseating as a necessary consequence of breach has been removed.[33]

Yet, the period of complete federal deregulation also proved short-lived. The ALP won federal office in 1983 and, as the centrepiece of its overhaul of the electoral laws,[34] introduced a public funding and disclosure regime. This is now contained in Part XX of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) (‘CEA’). The scheme first applied to the 1984 federal election – however, it was not the first in Australia, being preceded by New South Wales in 1981.[35] Regimes modelled on the federal regime spread to Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory in 1992 and Victoria in 2002.[36] It is notable that all these regimes have been ushered in by ALP administrations, with, where necessary, support from the Australian Democrats. In the last two decades, regulation in this area has overwhelmingly been the product of the social democratic parties.

In 1991, a more radical attempt was made by the Federal ALP Government to introduce a British-style ban on electoral broadcast advertising, in tandem with a system of mandatory free radio and television air-time for party electoral broadcasts. This attempt foundered on an activist, liberalist High Court.[37] That story has been well told elsewhere.[38] Free air-time, limited to the election period, is now only provided by the two public broadcasters.

This paper will now address the different facets of contemporary campaign finance regulation in turn.

In legislating for direct public funding of campaign expenses in 1983, the ALP relied on three central arguments. One was that elections should be decided on the quality of parties’ policies, not the size of their coffers. A second was that public funding would narrow the difference in financial resources to ensure reasonably fair electoral competition. The third was that it would reduce reliance on private donations and hence minimise potential corruption.

The federal system provides for post-election payment of public monies calculated according to the number of first preference votes received. It applies to both Senate and House of Representatives elections.[39] Registered parties appoint an agent to receive the funding generated by their candidates. In the case of unregistered parties or independent candidates, the funding is paid directly to the candidate or their agent.

The amount per vote is indexed and stood at $1.79 for the 2001 federal election. With well over 12 500 000 enrolments and a compulsory voting system in both Houses, the amount of public funding payable in consequence of the 2001 federal election could have exceeded $44.8m. The potential amount, however, is never paid in full, since voter turnout is always closer to 95 per cent than 100 per cent. Further, public funding is only ‘earned’ where candidates poll over four per cent of the formal vote, the result being that minor parties and independent candidates are under-funded. The actual amount of public funding paid after the 2001 election was hence just under $38.6m.[40] Federal funding is as of right, however, rather than by way of reimbursement. That is, claimants are not required to prove actual campaign expenditure.[41]

The older New South Wales model features five notable differences. First, public funding is split between a Central Fund and a Constituency Fund.[42] Two-thirds of the funding is distributed to registered parties (and, in the case of the Upper House, to groups or individual candidates not endorsed by any registered party). The remaining one-third is, in theory, distributed to Lower House candidates directly. However, in practice the major parties can require their candidates to ‘sign away’ this entitlement to the party’s head office thus further reinforcing the centralisation of political campaigning.[43] Significantly, the New South Wales system differs from the federal one in capping entitlements, so that no one party or candidate can receive more than half of either fund.

Secondly, registered parties at New South Wales elections are entitled to claim partial payments in advance of the poll.[44] Thirdly, the threshold of four per cent does not apply to a candidate who is actually elected (which can easily occur at New South Wales Upper House elections, where the quota is low). Fourthly, an extra tier of payments is made under the guise of a Political Education Fund.[45] This is open only to registered parties and equates to an annual entitlement to the cost of a stamp for every vote received at the previous Lower House election. These monies can only be used for seminars, or to disseminate printed information on party history and policies and newsletters to members. It cannot be used for electoral campaigning or conventions.[46] Finally, a specialist Election Funding Authority, a body formally distinct from the State Electoral Office, administers the whole funding and disclosure regime at New South Wales level.[47]

During heated federal debate over the cost and funding of campaigns in 1989, the Liberal Party suggested tax deductibility of donations as an alternative to public funding. The ALP agreed with the idea of tax deductibility, but desired it to be limited and saw it as additional – rather than alternative – to public funding.[48] In 1991, federal tax laws were amended to permit taxpayers to deduct up to $100 per annum from their assessable income for contributions (money or property) to political parties.[49] This includes party membership dues.[50] However, the law only covers contributions to federally registered parties. This limitation is presumably based on the taxation office’s desire for easy verification (the bona fides of a party being presumed from its entry on the register). But it also raises issues of differential electoral treatment of political movements that are not federally registered parties. The Liberal Party has also recently been pushing to substantially increase the deductible amount and extend it to corporate donations.[51]

Tax deductibility extends to electoral expenditure from the pockets of candidates.[52] However, any monies a candidate recoups, for example, from public funding, is offset as income, at least where parliamentary candidatures are concerned. (For local government candidates, deductions are subject to an annual limit of $1000.) Expenditure on entertainment at non-public gatherings, however, is not deductible (not so much to avoid treating as because the expenditure is considered private).[53]

There are no significant regulations governing electoral advertising, apart from minor provisions requiring authorisation and ‘tagging’ of political matter,[54] and some weak provisions limiting misleading advertising.[55] A ‘blackout’ on broadcast (but not press) advertising, however, remains in force for the three days prior to and including polling day at any parliamentary election.[56]

There are no mandatory grants of free-air time, although there is probably no constitutional impediment to using this as a form of subsidy ‘in kind’.[57] As a matter of internal policy, the two public broadcasting services – the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (‘ABC’) and the multicultural Special Broadcasting Service (‘SBS’) – even-handedly allocate blocks of free air-time at parliamentary elections. They rationalise this as an aspect of their public information role.[58] But the impact of these public allocations is limited. Viewers can simply switch to a commercial station when a ‘talking head’ electoral broadcast is aired. In any event, at the best of times the ABC and SBS achieve combined ratings equivalent to just one-sixth of the viewing public. The major commercial television network does, in tandem with the ABC, coordinate and freely broadcast any official debates between the Prime Minister and the federal opposition leader during the election campaign. However, unlike in the US, these leadership debates are not regulated. Rather, their number, nature and very existence are matters of convention and haggling, despite calls for a guaranteed and structured system of debates.[59]

Financial disclosure laws were a quid pro quo for public funding. They were ostensibly designed to introduce transparency and accountability. The reach of these laws has become an ongoing issue and the detail has been amended on many occasions. Here I will give a snapshot of the federal position as at the end of 2002.[60] The most important observation is that there are no restrictions on the amount or source of private donations.

In broad terms, disclosure obligations seek to ensure post-election revelation of certain details of donations and electoral expenditure by candidates and donors. The system also mandates annual returns by registered parties and their associated entities, requiring similar disclosure of certain donations received, as well as disclosure of totals of receipts, expenses and indebtedness.[61]

Disclosure works on a ‘cash accounting basis’. That is, only completed transactions are disclosable. As a result, for example, a party could in theory choose not to bank a donated cheque for some months, causing it to fall outside a financial year for reporting purposes. A candidate could similarly hold on to a cheque until months after polling day.

The obligation to disclose donations extends beyond registered parties, candidates and donors to include ‘associated entities’. These are bodies controlled by, or operating substantially for the benefit of, registered parties.[62] Disclosure also extends to third parties who incur expenditure on ‘electoral matter’, which is any matter intended or likely to affect voting.[63] The disclosure scheme is, in practice, predicated on a system of agents. Registered or not, political parties (that is, organisations whose objects include promoting its endorsed candidates for federal election)[64] must appoint party agents. Candidates in turn may appoint agents to handle their personal obligations.[65]

A donation, in the terms of the law, is any ‘gift’. Gifts are broadly defined to include any disposition of property, otherwise than by will, for inadequate consideration. They can include the provision of services other than volunteer labour.[66] Within 15 weeks of federal polling day, all candidates must lodge returns disclosing details of certain gifts received during the ‘disclosure period’ (other than donations received and used in a private, non-electoral capacity). If the candidate stood at the last election, the disclosure period extends back to their previous candidature; for new candidates it only dates back to when they announced their candidature.[67] The details to be disclosed are the names and addresses of the donors. However, whilst these returns must specify the total number of donors and the sum of all gifts received, donor details need not be disclosed if the total of that donor’s gifts is less than $200.[68]

This mirrors the obligation on those who donate to candidates (excluding donors who are direct electoral participants, that is to say, other candidates and registered parties, their branches and associated entities).[69] Every person or organisation that incurs ‘political’ expenditure in excess of $1000 at an election must also furnish a post-election return of donations received.[70] Here, ‘political’ expenditure goes beyond matter designed to influence voting and extends to the public expression of views on any election issue, as well as electoral gifts.[71] This obligation applies most commonly to lobby groups, companies and trade unions, but it also applies to unregistered parties. Further, it is drafted to attempt to capture conduits of donations, since ‘expenditure’ here is defined broadly to include the channelling of gifts.

Parties have a more regular obligation to furnish returns of amounts received. A registered political party and its branches must submit returns each financial year. These should include not just a sum of total receipts, but names and addresses in relation to amounts (including any gifts, loans or bequests) of over $1500 that were received from any individual source in that financial year.[72] However, as a salve to the administrators of parties – albeit at the expense of the transparency of the system – in calculating whether $1500 was received from any one source, individual receipts of less than $1500 from the same source need not be counted or disclosed by the party.[73] Similar annual returns must be made by entities associated with registered parties. In addition, where an associated entity makes payments to its party out of its capital, it must also disclose details of the contributors to that capital.

Annual reporting requirements also apply to certain donors to parties. These are donors who made annual gifts totalling $1500 or more to any registered party or branch, whether the total was achieved through several small donations, or a single large donation. The details required include the date and amount of each gift. For donor disclosure, indirect gifts are caught. That is, a gift to any person or body, made with the intention of benefiting a registered party, should be disclosed by the original donor. Similarly, a donor who channels gifts must also disclose details of any individual gifts received over $1000 that were used as part of a gift of $1500 or more to a party.[74] The obligation on donors to make annual disclosure, assuming it is widely understood and followed, is intended to act as an auditing ‘check’ on the accuracy of party returns.

It is unlawful for parties or candidates to receive anonymous donations in circumstances that might undermine their disclosure obligations. Thus, parties are not to receive gifts of $1000 or more, nor candidates to receive gifts of $200 or more, unless the true name and address of the donor is known at the time.[75] Reflecting a similar tenderness over non-commercial loans, the law was recently amended to render it unlawful for parties or candidates to receive loans of $1500 or more unless they keep a record of the loan’s terms and conditions as well as the lender’s name and address.

Expenditure disclosure is similarly governed by a two-phase system: partly post-election, partly annual. Further, as with donations, there are no limits to the amounts that can be spent. Candidates must make post-election returns of electoral expenditure incurred with their authority, although these do not cover expenditures made or authorised by a registered party or branch. Similarly, ‘third parties’ that incur total electoral expenditure in excess of $200 are required to detail that expenditure after polling day.[76] In this context, ‘electoral expenditure’ means the cost of disseminating matter intended or likely to influence voting, and explicitly extends to opinion polling related to the election.[77]

Annual expenditure returns are required of registered parties and their associated entities. However, to ease the accounting burden, these returns need only give total expenditure and not its detail.[78] Total indebtedness must also be declared, including the source and amount of any outstanding debts of $1500 or more incurred from a particular source that year.[79] Finally, media outlets are also required to make post-election returns of electoral advertising carried by them during the campaign.[80]

Some of the loopholes in this labyrinthine disclosure regime are discussed below. At this point, it suffices to note that whilst the AEC is given potentially broad investigatory powers,[81] the consequences of breaching the disclosure laws are far from draconian. Indeed maximum fines are quite low:[82]

(1) for failure to make timely returns, $5000 for party agents, $1000 for others;

(2) for incomplete returns or record-keeping, $1000;

(3) for knowingly misleading returns, $10 000 for party agents and $5000 for others.

Similarly, politico-legal consequences of disclosure breaches are virtually non-existent. Under the CEA, breaches of disclosure obligations do not taint an offender’s political rights, and non-compliance with them is non-petitionable. In other words, non-compliance cannot be used to invalidate an election.[83]

As already discussed, federal expenditure limits on candidatures were repealed in 1981. Such limits managed to survive in Victoria until a full overhaul of the electoral system in 2002. There, they covered both Houses of Parliament, but similarly applied only to expenditure ‘by’ a candidate and not parties as such.[84] Expenditure limits remain only in Tasmania.

Even in Tasmania, the limitations are confined to Upper House elections. They apply to any expenditure authorised by a Legislative Council candidate and are augmented by a prohibition on any expenditure in support of any candidate,[85] including expenditure by parties to promote their candidates’ elections.[86] In light of earlier Tasmanian jurisprudence, this would seem to preclude any widespread party advertising.[87] Partly as a result of this parsimony, Tasmanian Upper House elections are fairly low-key, if not ‘gentlemanly’. This is also a matter of political culture: elections in Tasmania, a small island State, are more localised, grassrooted and candidate-oriented than elsewhere. Tasmanian Upper House elections are thus largely devoid of open party politics and the law works in tandem with culture to reinforce this. Nothing prevents a candidate promoting their allegiance to a party, nor a party from endorsing a candidate (providing it does not spend money promoting this). But since there is no ballot labelling of Upper House candidates the system ensures a focus on the individual rather than the party. Further, electoral cycles for the two Houses are largely unsynchronised. Upper House members serve a six year term, with several standing for re-election on a fixed day each year; Lower House members serve a maximum four year term. As a result, only once in every three or four years is it even possible that party-dominated Lower House polls will coincide with an Upper House poll, and even then only a small proportion of the Upper House seats will be in question.

Curiously, for most of the 20th century, Australian electoral law did not explicitly acknowledge the existence of parties, despite their centrality to electoral politics. Whilst – with one odd exception – the Australian Constitution remains blind to parties,[88] electoral legislation, both formally and in its administration, is now heavily concerned with party affairs, particularly party registration.[89]

Registration was introduced at the federal level as a concomitant to the administration of the funding and disclosure regime.[90] Eight of the nine jurisdictions now provide for registration – a couple doing so merely to service their ballot labelling systems. The prerequisites for registration are outlined in the appendicised table. At federal level it is 500 unique members or a federal parliamentarian, plus a one-off $500 fee. The requirement to both possess and disclose the details of that many members has survived constitutional challenge.[91] Most established parties are organised by State and Territorial branches, as well as having a federal secretariat. The federal nature of Australian parties is reflected in the federal registration of branches and in federal funding, which is typically paid to those branches.[92] A side-benefit of this arrangement, as mentioned earlier, is that the federal disclosure requirements effectively extend to most of the electoral activities of the established parties, at whatever level. That is, there is no artificial distinction in fact or law between federal and State electoral activities when it comes to disclosure.

The downside of this is that branches may face double reporting obligations if they are registered federally and at State level. A second negative consequence is that there is no clear delimitation of whether donations are for federal, State, local government or general purposes. But this may be less irksome to those investigating allegations of the purchasing of political favours than may first appear. In a federal system a party’s state and federal branches can be at loggerheads as to how to handle a particular issue. A lobby group trying to push its own barrow may therefore target its donations to the branch level of the party that favours its interests. Also, donors would tend to donate money in the lead-up to the election of the particular level of government they wish to influence, further revealing any circumstantial connection between donation and jurisdiction.

Party registration is optional in all jurisdictions, but there are plenty of carrots. The chief benefits of registration lie in allowing a party:

(a) to control the public funding generated on the basis of votes received by endorsed candidates;

(b) to control the flow of its preferences in those upper house systems, such as the Senate, which permit voters to ‘tick a box’ as an alternative to numbering preferences for all candidates;[93] and

(c) to benefit from ballot labelling – that is, having the party’s name identified beside its endorsed candidates.

These benefits have furthered the historical trend to prioritise parties over individual candidacies in Australian political practice, but they have also come at a cost to party independence. These costs are not merely administrative although, unsurprisingly, the major parties use administrative burden arguments in lobbying to relax disclosure laws. The costs of regulation extend close to the border of freedom of association, since the legal status of political parties has been inverted as a result of registration. Formerly, parties (which are still typically unincorporated associations)[94] were immune from judicial review of their internal affairs.[95] Public registration and funding, however, have become the hooks on which common law judges now routinely hang the justiciability of party affairs.[96] This is leading to a form of juridification of party affairs, although to date, parties remain largely free to structure themselves as they see fit. However, it seems that even this may change, in the light of proposals for the public conduct of candidate preselections, with registration providing the peg on which regulation would hang.[97] In short, having been initially rationalised as an administrative adjunct to campaign finance law, registration has become a Trojan horse inside which the lawyerly and bureaucratic urge to regulate party activities is being smuggled into the field of electoral law.[98]

Australia, with one minor exception, has no citizen-initiated referenda.[99] However, referenda are mandatory to achieve amendments to the Australian Constitution. Federal referenda are governed by the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 (Cth).[100] Federal referenda are quite frequent, although they just as frequently fail unless they receive complete, bipartisan support.

Traditionally, expenditure on referenda has not been a concern, perhaps because referenda, with a few notable exceptions, are about legalistic questions, typically the apportionment of institutional power. Campaigning at referenda is generally confined to print discourse and advertising, and occasional public meetings. The centrepiece of most referenda campaigns is a relatively impartial, government funded education booklet containing official ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ cases, which is distributed to all electors.[101] In that sense, public funding of referenda campaigns exists. There are no expenditure limits as such, except to prevent further expenditure of federal money;[102] yet curiously, no limitation applies to State governments, who sometimes campaign when the balance of federal–State powers is involved. Nor, apart from old provisions requiring publishers and broadcasters to make a formal return of any advertising carried,[103] are there any disclosure requirements for referendum campaigns (except insofar as donations to federally registered parties are covered by the general disclosure laws).

As the unsuccessful 1999 Republic referendum proved, this relatively sedate picture is not applicable to referenda on questions of great symbolic or political import, where public passions and civic associations become mobilised.[104] Unusually, the government legislated in 1999 for public funding of formalised ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ campaigns beyond the neutral, official booklet: some $1 5m was spent, chiefly on slick television advertising. The Republic question is likely to be put to referendum again. Referenda campaign finance is bound to reappear as an issue then.

Before detailing a variety of reform proposals, it is worth crytallising the issues by outlining three recent examples of activities that have revealed flaws in the disclosure regime.

The first concerns the Liberal Party and its Greenfields Foundation trust. The Party’s treasurer discharged a multi-million dollar bank loan to the Liberal Party, in his personal capacity as a wealthy businessman. The debt was then assigned to the Foundation, with the Party repaying it on an interest-free basis. Disclosure of these arrangements only occurred (and then by the Party and not the businessman) after an AEC investigation.[105] Since then, provisions relating to associated entities, and in particular to the disclosure of indebtedness and the recording of loans from non-financial institutions, have been enacted. Broader questions were raised about why guarantees were not treated as ‘gifts’, and how to identify and enforce the law against associated entities, in particular trusts. Relatedly, the reach of the law to overseas donors and organisations (both formally and in practice) remains a live issue.

Second and more recently, the ALP has attracted criticism over its use of a professional fundraising firm called Markson Sparks.[106] The firm, for example, organised a tribute dinner, including an auction of memorabilia associated with Party icons, which raised $227 000. Only the total amount was disclosed. Had the Party – or even an associated entity – run the auction itself, donations of auctionable items worth $1500 or more would have been disclosable, as would have been many of the winning bids (even allowing for difficulties in determining the fair market price, and hence the excess ‘gifted’ consideration, with items such as autographed memorabilia). The Liberal Party also benefits from large-scale contributions from fundraising entities. The disclosure of only lump sum contributions from fundraisers has the potential to negate the accountability goal of disclosure laws, especially if significant payments that are essentially donations (such as a firm paying $10 000 for 10 places at a fundraising dinner) go publicly unacknowledged.

The broader issue raised by fundraisers is where ‘associated entities’ begin and end. A fundraising firm is not controlled by a party if it is formally at arm’s length from the party and enters into commercial arrangements with it. But what proportion of a fundraiser’s activities would need to be party fundraising before it would be said to operate ‘to a significant extent’ for the benefit of that party?[107]

Revenue through the sale of memorabilia, however, pales by comparison with the third concern, namely, the ‘sale’ of political access. At the lowest level, this is revealed by the confusion over how to characterise payments to attend or host party conferences, dinners and speeches. One bank that paid $5000 for staff to attend a Liberal Party function treated it as a nondisclosable ‘commercial’ or ‘corporate’ expense. Yet the Party disclosed it as a specific donation. The ALP, conversely, merely recorded as general receipts an amount of $15 000 paid by a telecommunications company for ‘observer status’ at a party conference.[108] At its worst, selling access to party officials and spokespeople amounts to the prostitution of access to political power. Examples of this include the formation of ‘round-tables’ and forums, to which businesses pay large fees to have direct input into policy consideration.[109] Of gravest concern is the perception of the sale of governmental favours. This concern has been most recently raised with regard to the exercise of discretion by the federal immigration authorities and Minister in favour of donors to the Liberal Party.[110]

There is a danger that the AEC will swallow the corporate view that such fees are valuable consideration, shelled out as part of doing business in Australia. Indeed one AEC handbook states that ‘value [ie, consideration] includes gaining access to lobby government ministers’.[111] On that reasoning, even large-scale donations are simply ‘part of doing business’ and their tax deductibility as an ordinary business expense would be undeniable! No matter how perfect the disclosure system, if the sale of political favours is assimilated as an acceptable part of the ‘commerce’ of parties, then politics risks collapsing into a business, not a public service.

Institutional scrutiny of federal electoral law is guaranteed, each electoral cycle, through two interrelated mechanisms. The AEC is required to produce a Funding and Disclosure Report after each election.[112] Then, the Federal Parliament’s Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (‘JSCEM’) investigates and reports on the overall conduct of the election.

A host of AEC recommendations about funding and disclosure remain on the table, some date back more than six years. In 2000, the JSCEM was specifically briefed to conduct a ‘Funding and Disclosure Inquiry’. It began to gather evidence, but the inquiry lapsed after more than a year.[113] The AEC made two detailed submissions to that inquiry, calling for urgent amendments to redress a host of ‘the most pressing problems’. The AEC’s second submission was written in a tone that mixed frustration with resolve. Some of these recommendations would represent a considerable tightening of the law to give the regime more bite. The AEC also called for a comprehensive review of the federal regime.[114]

The more important of the specific recommendations made by the AEC are that:

• arrangements entered into with the effect of reducing or negating a disclosure obligation should be treated as if they did not exist, thus requiring disclosure, and sufficient penalties should be enacted to deter such contrivances;[115]

• where a political actor omits to properly disclose a receipt or indebtedness of $1500 or more, the sum be forfeited to the Commonwealth;[116]

• a continued failure by a party to lodge a properly completed annual return be grounds for deregistration;[117]

• to avoid misreporting and confusion, parties’ annual returns identify donations separately from other receipts;[118]

• all entities and groupings whose membership or existence is significantly linked to or dependent upon a registered party be treated as associated entities for disclosure purposes;[119]

• prohibitions on the receipt of anonymous donations and loans be extended to associated entities;[120]

• since it is impossible for an outsider to know if anonymous donations are from the same source or not, the provisions limiting anonymous donations be given a cumulative threshold (regardless of source);[121]

• to deter the receipt of unlawful anonymous donations, the penalty be double forfeiture;[122]

• donations from outside Australia either be prohibited, or at least forfeited where the true original source is not disclosed in a return by the foreign source.[123] Similarly, overseas loans ought be forfeited when not fully disclosed by the recipient;[124]

• entities which control ‘shell’ parties at federal level assume full disclosure responsibilities under federal law;[125] and

• parties’ annual returns be accompanied by auditor reports.[126]

Not all of the AEC’s recommendations involve tightening the law. Some will undoubtedly be welcomed by the political class. For example, the AEC recommends that:

• the threshold for disclosure of donations to candidates be increased to $1000;[127]

• the threshold for triggering disclosure by ‘third’ party spenders be increased to $1000, and such organisations only be required to disclose donations;[128]

• donors who channel gifts to parties only be required to disclose details of gifts they receive of over $1500 (per source), to achieve parity in the disclosure rules;[129] and

• advertisers no longer be required to lodge post-election returns.[130]

The parties, of course, have their own agendas for reform, some resembling ambit claims. The organisational wing of the Liberal Party, whose more libertarian approach to campaign finance has been previously noted, wants disclosure thresholds to be raised to $10 000 per annum. Recalling that the established parties have both national and regional branches registered federally, if such a large threshold applied it would be possible to donate at just below the threshold to each entity, and thereby contribute nearly $90 000 per annum to the Party as a whole without proper disclosure. The parliamentary wing of the Liberal Party removed some of the ambit from that claim, when it (unsuccessfully) sought to legislate a $5000 threshold.[131] It now proposes a $3000 threshold.[132]

It is difficult to see why the disclosure threshold should be significantly raised. Presently, even under the AEC recommendations, a donor could donate nine amounts of $1499 per annum to each entity of a federally-organised party, and no specific disclosure by either party or donor would be required. Further, it would remain possible to make standing donations of, say, $1499 per month to the same registered party or branch, or associated entity, and the party as recipient would not be required to disclose the details: only the donor would need to disclose. Given that donors are much less likely to know the law, and are much harder to police than parties, this inverts the natural order. Since parties solicit donations, they are in the best position to know and enforce the law. The status quo is defended as administratively efficient, but in a computerised age it is hard to see why the law should not require parties to disclose all donations, great or small, with only a minimum cap (for example, receipts of less than $1000 per annum from the same source).

Relatedly, it is unclear why the disclosure provisions for candidates are tighter, in this regard, than for parties. This is unfair to independents.[133] Finally, the federal disclosure laws should require national party secretariats to amalgamate donation disclosures to include totals of donations from the same source, regardless of which branch received the donation (just as branches are currently required to report on all receipts by their constituents, such as sub-branches or campaign committees.)

A second cause célèbre for the Liberal Party has been the liberalisation of tax deductibility. The current Federal Government has unsuccessfully promoted a Bill seeking to extend deductibility to corporations. In the stand-off over this Bill, the most pressing tax reform, from the point of view of political equality, fell by the wayside. That reform concerned the extension of deductibility to independent candidacies and unregistered parties. There remains, however, broad support to raise deductibility to $1500 per annum (although the Liberal Party organisation advocated a 100-fold increase to $10 000 per annum).[134]

The Australian Democrats, in contrast to the Liberal Party, have sought a considerable tightening of disclosure and donation law. The Democrats want instant disclosure and publicisation of any donations exceeding $10 000, and a ceiling on donations from any single corporation or organisation.[135] Tham joins the Democrats in advocating caps on donors (if not an outright ban on donations).[136] The AEC, however, recommends against donation limits, pointing to problems of definition and enforcement.[137]

These definitional problems raise some fundamental issues of equal treatment. For instance, since the ALP receives significant ‘affiliation’ fees from unions, caps on ‘donations’ would have to be broadened to include ‘contributions’. Further, to rework an argument of one conservative US scholar, if donations were to be capped, should not the amount of time individual activists can commit to causes be capped, or the number of words a polemicist can write? Some ‘scribes’ can easily publicise their views: journalists, in particular, if not academics! Is it fair that the views of the less articulate or favoured, who nonetheless wish to use their money to support political viewpoints, be subject to greater regulation?[138]

The larger concern with caps on donations, however, involves their workability. It is generally assumed that US-inspired contrivances would be adopted to avoid any caps. Given the Australian experience, with the use of ‘associated entities’ and fundraising agencies to place donating at a formal remove from the parties, this seems a real possibility.

The Democrats have also led calls to introduce greater shareholder control and accountability over corporate donations. Their party policy includes requiring shareholder approval of ‘donation policies’ of public companies, and full donation disclosure in company annual reports. Ramsay et al, in their study on corporate donating, support this proposal.[139] Such a reform would be commendable, but it is likely to be a leaden political football as far as the major parties are concerned. The ALP would instinctively support corporate reform, but it would implicate ALP sensitivities about the freedom of unions to contribute affiliation fees and donations (even given that unions, unlike companies, are democratically organised).

The option I want to float, to cover all parliamentary elections, combines a greater level of public funding, in return for strict expenditure limits and expenditure accountability.[140] Admittedly, any proposal to increase public (that is, taxpayer) funding of parties would be difficult to sell, even with bipartisan support. But the cost of campaigning has tended to rise at a rate outstripping inflation and thus public funding levels have, by default, become less generous over time.[141]

It needs to be realised that genuine democracy requires parties to be able, in rough equality, to afford to commit resources to policy generation, and not simply campaigning. Some critics counter that guaranteed funding has accelerated the atrophying of ‘grassroots’ membership activity. But it is not clear that this has been a product of public funding. Public funding assists by defraying the party’s campaign debts after an election. But it hardly covers all the running expenses of a party’s administration or its many sub-branches. As a result, the financial, as well as the policy health of parties, will always require an engaged membership. Further, public funding in Australia has occurred without expenditure limits. Parties that can raise significant amounts of money through donations at whatever level are at an advantage over their competitors, as they remain entitled to use that money in campaigning.

The real problem with campaign finance law, with regard to the decline of the mass-membership base of parties, is that grassroots fundraising has paled in comparison to corporate donations. That is, the attention and affection of party apparatchiks have turned away from individual members and towards corporate donors. If donation caps were feasible, this would be a strong argument in their favour.

Admittedly, the original conception of public funding as a means of weaning parties off private donations has proven overly ambitious. But in my estimation, the Achilles’ heel of the project has been a failure to link public funding to expenditure limits. Strongly audited electoral expenditure limits on parties, candidates and associated entities must be considered. Such limits will help to breed a more modest campaign culture, something which anecdotal evidence suggests that voters would prefer. Currently, the parties, like sporting clubs without a salary cap, are locked into an escalating advertising war which needs to be moderated. Further, as Cass and Burrows argue, there is no reason why moderate expenditure limits should fall foul of constitutional liberalism. After all, such limits remained on the statute books for nearly 80 years at federal level, and still exist in one State.[142]

It will be objected that, like pressing down on the proverbial waterbed, any imposition of expenditure limits may only cause a flow of money away from parties and candidates to third parties. After all, governments already make notoriously excessive use of public monies to promote their activities prior to elections, with advertising that is so political that it requires authorisation ‘tags’.[143] How much more likely will political elites be to invent ways of circumventing campaign expenditure limits, for example by setting up ostensibly independent bodies to engage in electoral advertising?[144] Even if similar expenditure limits on individual bodies or persons are constitutionally permissible, clever lawyers, in order to circumvent such limits, may only need to tweak the formal structure of such ‘fronts’.[145] In Issacharoff and Karlan’s famous metaphor, regulators face the problem of the ‘hydraulics’ of campaign finance – money is fluid and tends to find its own level.[146]

But to assume the hydraulics of money politics are uncontainable is to take an odd view of electoral culture in Australia. Australia is not like the US. First, it does not have such a deeply-rooted history of individual expression through civic associations. In the US, a proliferation of civic groups engaging in ground-up politics is a natural phenomenon. In Australia, a more statist culture has historically prevailed, and a preference remains for a more limited and ordered approach to electoral activity and lobbying. Certainly there are a number of peak groups, from the major trade unions and professional associations through to the chief environmental and industry groups, who sometimes voice their electoral preferences during campaigns. But they do so only to the extent that their voices will be respected because they are known to be independent organisations, answerable to their members’ interests. In short, unlike the US, there is no cacophony of political speech into which mouthpieces for party interests, active only around election time, could easily blend.

Best of all, there is a contemporary model to draw upon. Expenditure controls on parties and third parties (as well as candidates) have recently been instituted in the UK, following the Neill Committee recommendations.[147] Australian electoral practice, which shares more with the UK than the US, will be in the happy position of being able to monitor the success and workability of this regime before implementing such limitations.

The beauty of expenditure limits is that electoral expenditures – particularly advertising and canvassing generally – are inherently public, at least compared to donations, which occur in private. They may, therefore, be more readily tracked, not least since rival candidates and parties are in a position to monitor, estimate and complain of excessive expense. Donations, on the other hand, aside from being difficult to detect, have no history of limitation in Australia (with the peculiar recent exception of large donations from the gaming and casino industry in Victoria).[148]

A final question for my reform proposal is whether public funding has helped create greater political equality. That is, has public funding created a more level playing field for electoral competition? On first glance it appears to have done so as between the major parties – the conservative coalition and the ALP. But any conclusion on this is confounded by the ALP’s contemporaneous move from being a relatively interventionist party of the economic left, to a party of economic rationalism. Combined with its long period in federal office from 1983–96, this has rendered the ALP almost as popular to corporate donors as the conservative coalition. Indeed, some might say that public funding helped this transition in the ALP, in that it encouraged centralisation and a minimisation of reliance on grassroots fundraising. However, regardless of whether public funding has helped equalise competition between the parties of power, the four per cent threshold plainly discriminates against small and ‘start-up’ parties. In the interests of political equality, this threshold should be removed or lowered, to provide for truly pro rata public funding.

Despite rationalisation of local government in Australia, there remains a multiplicity of councils, many of whose elections are run on shoestring budgets by shire clerks or CEOs. Local government electoral law, although complex and variable even within individual States, is thus not usually administered by a central, standing electoral authority. In many smaller shires, parties do not dominate and campaigning is low-key and ‘pre-electronic’, focusing on posters, door-knocking, meetings and ads in the local press. But in larger cities, parties predominate and elections may be run by fully-independent commissions.

Assumptions that money politics at the local government level is not an issue, merely because some local elections are uncelebrated events, need challenging.[149] Certainly, where provincialism flourishes and a distrust of sophisticated candidates and campaign machines is augmented by grassroots interest in local politics, money politics is sublimated. Further, compulsory voting only applies to some local government electoral jurisdictions. Even there, apathetic citizens, whose votes might be most swayed by expensive, image-conscious advertising, tend to ignore the compulsion and forfeit their ballots with relative immunity.

However, these arguments only focus on the corrupting influence of money on electoral politics in terms of unfair electoral competition and outcomes. Local government, par excellence, is the site where electoral donations may be a quid pro quo for corrupt purchase of governmental patronage. This is because of local government’s power over issues of immediate pecuniary value to developers, such as land zoning and construction approvals. Indeed, the rationale for State Constitutions not guaranteeing local democracy is the need to retain the power to put corrupt councils under administration. Accountability, or at least the information about electoral patronage and expenditure needed to permit public questioning, is thus no less needed at this ‘lowest’ level of government. It is odd, then, that a majority of State and Territory Parliaments have some form of disclosure regime for their own elections, but tend to ignore the issue at local government level. The lack of strong disclosure laws across all local government elections is doubly damning, since the absence of a developed system of party politics at smaller local government elections means that the over-arching federal disclosure system (centred on the registered party system) is inapplicable to most local politics.

No campaign finance regulatory system will please everybody. Yet in Australia it is almost universally accepted that parliamentary elections require some level of disclosure law, and the parties have grown content with public funding. It is assumed that the fierce nature of competition for electoral, and hence political power, militates against political culture spontaneously developing a self-enforcing ethic about its own financing. The impression one gets from the literature in this field is that the law is enmeshed in a continuing battle, akin to a game of ‘cat and mouse’. This is accompanied by an implicit belief that despite – or indeed through – this struggle, incremental progress will be achieved. Such progress, it is thought, will be slow but relatively assured, given sufficient vigilance and legislative courage in the face of vested interests and creative lawyering. At the root of this rationalist faith is a general, if unstated assumption, that some regulation is better than none, and that, other things being equal, more regulation, rather than less, is probably necessary.

I would like to question whether and when it might be possible to reach a point in a funding or disclosure system where the imperfections are such that some funding or disclosure law becomes worse than none. This may seem paradoxical. Consider general regulatory theory, where benefits and penalties, and notions of ‘need’ and ‘wrongdoing’, are central. Few would argue that, simply because the letter and spirit of the law cannot be perfectly policed, or an equal distribution of benefits achieved, the law must therefore give up the regulatory game. For example, it is usually better to catch a few wrongdoers than none, just as it is better to pay some welfare recipients even if other deserving cases miss out. No wrongdoer can claim mitigation on the basis that they were unlucky to be caught when others are escaping detection, and no-one can deny another needy person a benefit simply because they did not receive one.

But this model is based on a simple, linear idea. If we remove as much dirt as possible, then hygiene is advanced. And if we give as much welfare as possible then poverty is mitigated. But administering and policing electoral politics is more complex than this. If some types of political actors are more likely to get caught in the disclosure net, or to have their fundraising or campaign finance position affected than others, then the law may distort more than it equalises. And such distortion could affect core values like fair electoral competition and improving the diversity and strength of political culture.

This may occur when certain restrictions and benefits differentially apply to some groups over others. A classic illustration is the threshold to ‘earn’ public funding, which affects the ability of small parties to establish themselves, unless they can launch with a ‘splash’. For example, a party that achieves exactly four per cent of the Senate vote evenly across Australia can rely on receiving over $800 000. Such a sum would be sufficient to maintain a national office across the life of the Parliament, as well as fund a modest campaign at the next election. A party receiving three per cent of the vote can expect nothing. Historically, this situation advantaged the Australian Democrats who, to take the 1998 Senate election as an example, received more than 11 times the funding of the Green alliance, its rival for the progressive vote, although it polled only three times the Green vote. That the two parties are also rivals for the balance of Senate power only heightens the unfairness of the funding position.

Some might defend this outcome as inevitable, since any cut-off will have arbitrary effects. Some may even see it as desirable, arguing that it serves, not so much to suppress political rivalry, as to encourage parties of similar hue to amalgamate.[150] So let us consider a more subtle distortion. A minor party that can launch with a ‘splash’ and garner over four per cent of the vote will secure the funding it needs to perpetuate and grow. The eruption of the One Nation Party (‘ONP’) on the electoral scene is salutary. The ONP was driven chiefly by nationalist rhetoric and its limited platform focused on racial issues. It benefited from the controversy that these generated and from its charismatic leader. The resultant ‘splash’ earnt it very substantial sums of public funding at two elections in its first full year of operation. This is not to say that the ONP did not ‘deserve’ this funding: it managed to build up a great deal of grassroots support, especially in regional Australia. Rather, the lesson is that minor parties attempting to build a more generalist support base, with less attention-grabbing positions but more comprehensive policies, are pushing a barrow up two hills. They face media occlusion, since what is less scandalous is less newsworthy. But they also receive no favours from the electoral apparatus because of the absence of pro rata public funding.

One can analyse many other features of the law from this perspective of equal political competition. For instance, on its face, the limitation of tax deductibility to small donations and its denial to corporations are well matched to democratic theory. After all, only individual citizens have the right to vote and wealth is not meant to purchase a greater say. The Liberal Party, in pushing for a much higher level of deductibility and for its extension to corporate donors, is accused of seeking an unfair advantage, since it historically has received the greatest share and is relatively more reliant on corporate donations. However, it can retort that the current system provides advantages to its chief rivals. For instance, the ALP benefits from significant donations from trade unions, who, as not for profit organisations, are unaffected by tax deductibility. Yet the ALP, as the alternative party of government, can also bank on a sizeable amount of corporate donations. Meanwhile, the ONP, which appealed primarily to alienated, lower-middle class conservatives, had a demonstrated ability to raise monies from large numbers of small donors.[151] Since the ONP, with its anti-economic rationalism and antiglobalisation rhetoric, attracts little support from either the corporate sector or from higher income earners, the present tax deductibility provisions suit it well.

The cases I have just outlined are mere instances of a well-recognised general phenomenon. The differential receipt of public subsidies can distort a competitive environment – in this case, the electoral playing field. And, if the nature of political competition is affected, the tenor of political debate can also be affected. What is perhaps less well-considered is if or when disclosure laws might operate in a similar way.

At first glance this might seem paradoxical. Disclosure means knowledge. Science leads us to believe that any knowledge is a good thing, provided we are aware of its source and veracity. From this point of view, partial disclosure is inherently better than none, since it provides at least a partial picture and some accountability. But this is to forget that electoral politics is competitive by nature, and that the disclosure process itself is inherently political in the sense that subsequent media analysis may have political consequences.

The problem with complex disclosure laws that are imperfectly drawn or policed, is twofold. First, the laws inevitably have some differential impact. Parties or candidates who are less well-organised or advised are more likely either to fall foul of the law through ignorance, or slavishly follow official guidelines, such as the AEC’s Funding and Disclosure Handbooks. Conversely, parties and donors who are well-resourced are better-placed, as recent history shows, to obtain sophisticated legal and accounting advice with which to design schemes to avoid or obscure the reach of the disclosure law.

Second, the electorate may receive a distorted picture. This can occur in a variety of invidious ways. I will give three, in increasing order of seriousness. First, those donors who are open about their activities may receive opprobrium more fairly directed at secretive donors. Second, those parties and entities that are more scrupulous in abiding by their disclosure obligations open themselves to greater public scrutiny than those that do not. Whilst such openness may be used to advantage (for example, by allowing the virtuous refrain, ‘We are open; are our opponents?’) there is also a danger that public impressions will be tilted against those parties who declare more, rather than less. If that were the case, imperfect disclosure laws may be less valuable than other kinds of informational regime, such as an anonymous survey of business donations.

Finally, there is a danger that unintentionally selective enforcement, or selective promotion, will create false impressions of the nature of the overall problem. By way of analogy, consider how ‘blue-collar’ crime (that is, street and property offences) is overrepresented both in official statistics and by the public, relative to ‘white-collar’ crime, which is harder to detect, prosecute and publicise. Australian electoral law is in an analogous position. Valiant attempts by small sections of the ‘quality’ press and the AEC aside, the issue of electoral finance reform in recent years has received only secondary attention in parliamentary debates[152] and the media at large. Yet, allegations of crude electoral offences such as personation and multiple-voting on quite limited scales, and revelations of branch stacking leading to relatively small numbers of false enrolments, consumed three inquiries and acres of newsprint in 2000.[153] Crude electoral fraud is to money politics as blue-collar crime is to white-collar crime.

In the end, the question for the Australian funding and disclosure regime is whether its manifold imperfections are fatally flawed or remediable. The range and tone of recent recommendations for reform raise the question of whether disclosure, in particular, should be likened to a game of ‘cat and mouse’ or a Sisphysean task.[154] The AEC could be forgiven for thinking the latter. There is probably the energy and willpower to sustain one thorough round of reform of the present model. After that, if the mice continue to triumph over the cat, or worse, the stone overcomes Sisyphus, then the choice will be stark. Either we scale back the attempt to regulate, or we up the ante to a more radical model involving expenditure caps or donation limitations.

APPENDIX: AUSTRALIAN PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION FINANCE LAWS – KEY FEATURES BY JURISDICTION

[*] Senior Lecturer, Law Faculty, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia: g.orr@griffith.gu.edu.au.

The law is stated as at the end of 2002. Versions of this paper were given at the Money Politics International symposium, Florence, 18–19 October 2001 and a joint University of Columbia/Institute of Advanced Legal Studies seminar, London, 5–6 July 2002. Thanks to Professor Keith Ewing for his kind invitations, Jodie Thomas for research assistance and most particularly the Electoral Council of Australia and the Australian Research Council for funding Professor George Williams’ and my larger project on Australian electoral law, to which this article is a contribution.

[1] Minor party, independent and ‘protest’ voting now routinely measures in the 15–20 per cent range.

[2] Adrian Brooks, ‘A Paragon of Democratic Virtues? The Development of the Commonwealth Franchise’ [1993] UTasLawRw 14; (1993) 12 University of Tasmania Law Review 208, 208–9. Here, Brooks discusses the ‘myth’ of seamless enfranchisement. Cf Marian Sawer, ‘Pacemakers for the World?’ in Marian Sawer (ed), Elections: Full, Free and Fair (2001) 1.

[3] Leading psephologist Malcolm Mackerras employs ‘semi-proportional’ to describe the relatively high quotas required for election to the Senate. Proportional representation, under a Hare-Clark method, also applies in two of the smaller lower houses (Tasmania and the ACT).

[4] Local government remains a creature of (largely unfettered) State jurisdiction. Whilst many State Constitutions incorporate reference to or safeguards of the existence of a regime of local government, only South Australia has an entrenched system of elected local government.

[5] Victoria’s public funding regime is the most recent: Electoral Act 2002 (Vic) pt 12. It imposes no real disclosure regime, but merely relies on State parties filing copies of any returns they are required to file under the federal regime. Western Australia, conversely, has an independent disclosure regime for State elections, but no public funding.

[6] See, eg, Ian Farrow, ‘Politicians Inc’ (1995) 47(4) Institute for Public Afairs Review 8.

[7] See, eg, Denny Meadows, ‘Open Election Funding or Hide and Seek’ (1988) 13 Legal Services Bulletin 65.

[8] Commonwealth, Election Funding Disclosure and Australian Politics: Debunking Some Myths, Parl Research Service Paper No 21 (1995) 1 (emphasis added).

[9] Australian Electoral Commission (‘AEC’), Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters Inquiry into Electoral Funding and Disclosure, Submission No 15, 3 August 2001, [1.4], <http://www.aph.gov. au/house/committee/em/f_d/subfifteen.pdf> at 10 June 2003.

[10] Ernest Chaples, ‘Public Funding of Elections in Australia’ in Herbert A Alexander (ed), Comparative Political Finance in the 1980s (1989) 76. Chaples had long been monitoring the development of finance and disclosure laws in NSW: Ernest Chaples, ‘Public Campaign Finance: New South Wales Bites the Bullet’ (1981) 53 Australian Quarterly 4; Ernest Chaples, ‘Election Finance in New South Wales: the First Year of Public Funding’ (1983) 55 Australian Quarterly 66. For an exceptional legal foray, see Teresa Somes, ‘Political Parties and Financial Disclosure Laws’ (1998) 7 Grifith Law Review 174.

[11] Deborah Cass and Sonia Burrows, ‘Commonwealth Regulation of Campaign Finance: Public Funding, Disclosure and Expenditure Limits’ (2000) 22 Sydney Law Review 447.

[12] Joo-Cheong Tham, ‘Legal Regulation of Political Donations in Australia: Time for Change’ in Glenn Patmore (ed), The Big Makeover: A New Australian Constitution (2000) 72; Joo-Cheong Tham, ‘Campaign Finance Reform in Australia: Some Reasons for Reform’ forthcoming in Graeme Orr, Bryan Mercurio and George Williams (eds), Realising Democracy: Electoral Law in Australia (2003).

[13] Ian Ramsay, Geof Stapledon and Joel Vernon, Political Donations by Australian Companies (2001); Ian Ramsay, Geof Stapledon and Joel Vernon, ‘Political Donations by Australian Companies’ (2001) 29 Federal Law Review 177.

[14] A noteworthy exception is Hare v Gladwin (1998) 82 ALR 307. There, the AEC successfully defended its right to demand the production of documents from a trust used by the Northern Territory Country Liberal Party to channel the bulk of its fundraising.

[15] Lisa Allen, ‘Invisible World of Political Donations’, Australian Financial Review (Sydney), 20 April 2001, 72–3.

[16] The bulk of this is in the disclosure regime. This figure does not include operationalising regulations or the party registration provisions.

[17] Allowing of course that the breakthrough legislation on funding and disclosure originated in New South Wales. That the federal system now exerts centripetal force is illustrated by Queensland’s ‘cut and paste’ adoption of the bulk of the federal regime: Electoral Act 1992 (Qld), s 126B and Schedule.

[18] Federal law mandates that polling days be kept distinct, Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) s 394.

[19] See below n 125 and accompanying text.

[20] Tham, ‘Legal Regulation of Political Donations in Australia: Time for Change’, above n 12, 78–80.

[21] Cass and Burrows, above n 11.

[22] Ibid 453–7.

[23] The high water mark of that view in Australia was the High Court’s overturning of a broadcast advertising ban in Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (1992) 177 CLR 106 (‘ACTV v Commonwealth’). This was controversially achieved by ‘implying’ a constitutional freedom of political communication.

[24] Cass and Burrows, above n 11, 454–5.

[25] Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918–1980 (Cth) pt XVI (superseding Commonwealth Electoral Act 1902 (Cth) pt XIV).

[26] R v Tronoh Mines Ltd [1952] 1 All ER 697 (interpreting laws restricting expenditure and ‘promoting the election of a candidate’ as inapplicable to advertising promoting or denigrating parties generally).

[27] The original limits were set in the inaugural Commonwealth Electoral Act 1902 (Cth) s 169.

[28] Commonwealth Electoral Act 1946 (Cth) s 4.

[29] Enforcement was far from stringent. Early on, the Chief Electoral Officer adopted a practice of not prosecuting candidates who did not bother to account for their expenditure if they happened not to win the seat they were contesting: Patrick Brazil (ed), Opinions of the Attorneys-General of the Commonwealth of Australia: Vol 1 1901–1914 (1981) 500–1.

[30] Re Electoral Act 1907 [1979] TASRp 28; [1979] Tas R 282. The Tasmanian limit was then $1500.

[31] Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Act 1980 (Cth).

[32] In effect, this brought the expenditure of parties within the strict limits on candidate expenses: Attorney-General v Liberal Party of Australia, Tasmanian Division [1982] TASRp 8; [1982] Tas R 60.

[33] For the current Tasmanian position, see below nn 85–7 and accompanying text.

[34] Commonwealth Electoral Legislation Amendment Act 1983 (Cth). The reform was preceded by a wide-ranging inquiry, see Joint Select Committee on Electoral Reform, Parliament of Australia, First Report (1983).