University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

AMANDA LYE[*]

Jurisdiction over crimes at sea was, until recently, exercised in accordance with Admiralty rules or Imperial Acts.[1] The common law jurisdiction was limited to the low water mark of a State’s external coast.[2] In 2000, the Commonwealth, together with the Australian states and the Northern Territory, enacted co-operative scheme legislation.[3] The scheme attempts to ensure a national uniform approach to crimes committed at sea.[4] The Australian Government is increasingly using the Australian Defence Force (‘ADF’) to enforce the laws of the Commonwealth. This in turn has caused some uncertainty as to the jurisdictional application of the Crimes at Sea Act 2000 (Cth)[5] (‘CaSA’) and the Defence Force Discipline Act 1985 (Cth) (‘DFDA’). The CaSA was drafted in an attempt

to give Australia a modern crimes at sea scheme. The increasing incidence of people smuggling in the last year has highlighted the importance of having an effective legal regime to govern the seas around Australia’s coastline…The new crimes at sea scheme will be simpler to understand and apply, and will result in more effective law enforcement…The bill implements a new national, uniform, cooperative scheme to apply Australian criminal law offshore.[6]

The purposes of the CaSA are stipulated as not only giving legal force to the co-operative scheme but also ‘to provide for the application of Australian criminal law in certain cases beyond the area covered by the scheme’. Therefore the CaSA legislates Australian criminal jurisdiction not only in an area up to 200 nautical miles or the outer limit of the Continental Shelf, whichever is the greater, from Australia’s baselines, but potentially beyond and into other countries’ territorial waters.

The effect of the CaSA would be to enforce Australia’s criminal law beyond 200 nautical miles from Australia’s baseline. In comparison, the DFDA imposes a disciplinary code on ADF personnel both in and outside Australia.[7] The uncertainty regarding CaSA and the DFDA is that two legislative schemes concurrently apply to criminal actions of ADF personnel when at sea. Some ability to determine the jurisdictional factors between the two Statutes is required.

The DFDA has been in operation for 20 years.[8] The only existing document which assists analysis regarding the application of State or Commonwealth criminal law to actions of ADF personnel is a Defence Policy document.[9] This Instruction assists Commanders to determine the jurisdiction of criminal actions of ADF personnel.[10] The Instruction utilises the ‘service connection’ test applied by Brennan and Toohey JJ in Re Tracey; Ex Parte Ryan[11] (‘Re Tracey’) to determine jurisdiction. This test is by no means an exact science, a fact that some ADF Commanders find frustrating.

To date, there have been four High Court judgments on the issue of the jurisdiction of the DFDA[12] (the ‘Jurisdictional cases’). The most recent High Court judgment, Re Colonel Aird; Ex parte Alpert (‘Alpert’)[13] was handed down on 9 September 2004. Out of the four cases, it is the only one to determine jurisdiction of the DFDA overseas. Since it was handed down, the Defence Instruction has not been updated to reflect the extension of the DFDA ’s application. The extension to the DFDA is, according to Kirby J, ‘erroneous’ and a ‘misapplication of the Constitution…’.[14] With this view in mind, it is arguable that the Defence Instruction is now obsolete and, therefore, there is no up-to-date document to assist ADF Commanders when determining criminal jurisdiction.[15]

With only an out of date document to assist them, determining the jurisdiction of the CaSA is made all the more difficult for Commanders. Further complicating matters are the arguments contained in the Jurisdictional cases[16] regarding the extent of the defence power under the second limb of s 5 1(vi) Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1901 (‘the Constitution’).[17] These arguments raise the question as to whether or not actions by ADF personnel conducted under the second limb are military in character. If not, then it is possible that any criminal actions by ADF personnel when engaged in activities under the second limb of s 5 1(vi) fall outside the ambit of the DFDA but within the jurisdiction of the CaSA.

The activities conducted by ADF personnel under the second limb of s 51 (vi) of the Constitution that are generally not considered to be typically military or defence in nature are those relating to the enforcement of the ‘laws of the Commonwealth’. These non-defence activities include enforcement of breaches of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth), Fisheries Management Act 1991 (Cth), Migration Act 1958 (Cth), Customs Act 1901 (Cth), Navigation Act 1912 (Cth) and Maritime Transport Security Act 2003 (Cth).[18] This expansion in the use of the military to enforce Commonwealth laws has recently attained a rising profile in the Australian media. The monitoring, detection and apprehension of illegal fishing operators centred in the Australian Fishing Zone (‘AFZ’) adjacent to Heard Island and McDonald Islands (‘HIMI’) and Northern Australia[19] has increased the involvement of the Royal Australian Navy (‘RAN’) and other ADF assets in such activities.[20] The apprehension of an illegal fishing vessel catching Patagonian Toothfish in the HIMI AFZ was the most notable of the recent high profile operations. The Tampa incident also saw the ADF involved in the political machinations of the Government. The main consequence of the ADF involvement in Tampa[21] and in Fisheries enforcement is the diversion of ADF materiel from their primary role and into the undesirable territory of Commonwealth law enforcement.[22]

At the time of writing there are no articles[23] that assist in a working application and understanding of the CaSA. Users of the legislation have to resort to interpreting the wording of the CaSA itself. This paper seeks to analyse and discuss the application of the CaSA and provide guidance to those who need to understand the CaSA.

This paper will discuss the effects of the Jurisdictional cases, if any, on the operations of the co-operative scheme in the various Australian maritime zones. Specifically, discussion and analysis will centre on the actions of ADF personnel undertaking enforcement activities under the various Commonwealth laws which provide them with powers to conduct boarding parties (referred hereafter as ‘non-defence activities’). These non-defence activities are conducted to ‘execute and maintain the laws of the Commonwealth’ via the second limb of s 5 1(vi) of the Constitution. This paper also seeks to analyse the conflict in jurisdictional application between the CaSA and the DFDA. This jurisdictional issue is important to ADF Commanders as the issue currently exists, arguably, in a vacuum of policy guidance. Further, this issue provides even more of a challenge for ADF Commanders as non-defence activities, specifically interdiction and boardings, are becoming more commonplace and high profile.

An increasing governmental trend is the use of Royal Australian Navy (‘RAN’) assets to conduct boarding parties for non-defence activities. The current ADF Doctrine[24] allows for ADF assets to be employed as boarding parties. This Doctrine relies upon the defence power to engage ADF assets and sets out the various reasons for ADF support, which include the enforcement of international customary laws, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (‘UNCLOS’),[25] operational requirements and Commonwealth laws.

Generally, organising and establishing boarding parties is a whole of ship activity.[26] A set core personnel is stipulated for boarding parties. The boarding team will usually consist of three elements: Bridge team, Security team and Sweep team.[27] Each team has set tasking during the boarding. The Bridge Team conducts information gathering and is generally located at the Bridge of the boarded ship. The Security Team locates all crew and ensures the security of the crew and ship superstructure from internal and external threats during the conduct of the boarding. The Sweep Team is responsible for the inspection, maintenance and control of the ship’s engine room. ADF personnel selected as boarding party personnel require on-going specialist training and must also possess a high level of fitness and display professionalism, good communication skills, critical judgment skills under stress and knowledge of the Law of the Sea and in particular the degree of force they can employ.[28]

Boarding parties are currently being used in three ADF operations:[29] Operation Cranberry, Operation Relex I and Operation Mistral.[30] Operation Cranberry operates sea, air and land surveillance in Northern Australia. The ADF contingent, primarily RAN Patrol Boats and Army personnel, support the civil agencies, such as Customs and Coastwatch to detect ‘any illegal activity within Australian waters’.[31] Operation Relex I is the successor of the first operation during which the MV Tampa incident occurred.[32] The mission of this ADF operation is to protect Australia’s borders. The Operation is a ‘whole-of-government’ program to ‘detect, intercept and deter vessels carrying unauthorised arrivals from entering Australia through the North-West maritime approaches’.[33] In November 2003, a boarding party from HMAS Geelong boarded an Indonesian fishing vessel Minasa Bone. The Minasa Bone had arrived at Melville Island, located off the coast of the Northern Territory, with illegal immigrants on board. The vessel was detained under s 245F(8) of the Migration Act for contravening the Act by bringing individuals into Australian waters unlawfully.[34]

Operation Mistral is an ADF deployment providing ‘support to the civil agencies enforcing Australian sovereign rights and fisheries laws in the Southern Oceans’.[35] This Operation provides ADF personnel to support non-defence activities pursuant to the second limb of the defence power for the enforcement of the ‘laws of the Commonwealth’. There have been several high profile pursuits and interdictions of suspected vessels since 2001. The second longest hot pursuit of an illegal fishing vessel was the 14 day pursuit of the fishing vessel South Tomi in 2001. The South Tomi was detected trawling illegally in Australian waters near Heard Island. It was eventually boarded 320 nautical miles off South Africa by ADF personnel assisted by the South African defence forces.[36] Another apprehension which received a high media profile was the pursuit of the illegal fishing vessel Viarsa in August 2003 in the Australian Fishing Zone around HIMI. After 21 days of pursuit over 3,900 nautical miles, the boarding of the FV Viarsa ended the longest pursuit in Australia’s maritime history.[37] The vessel was brought back by a RAN steaming party to Fremantle under arrest.[38] In January 2004, the RAN apprehended another illegal fishing vessel Maya V again in Australian waters adjacent to HIMI.[39] In this case, the boarding party had to overcome dangerous seas to board the Maya V by fast rope. Under escort by HMAS Warramunga and with a RAN steaming party on board, the Maya V was brought back to Fremantle.[40]

With the frequency of boarding parties increasing, an understanding of the Australian maritime zones and the jurisdiction of the CaSA and the DFDA is required by ADF personnel, to ensure compliance with Commonwealth and international customary laws.

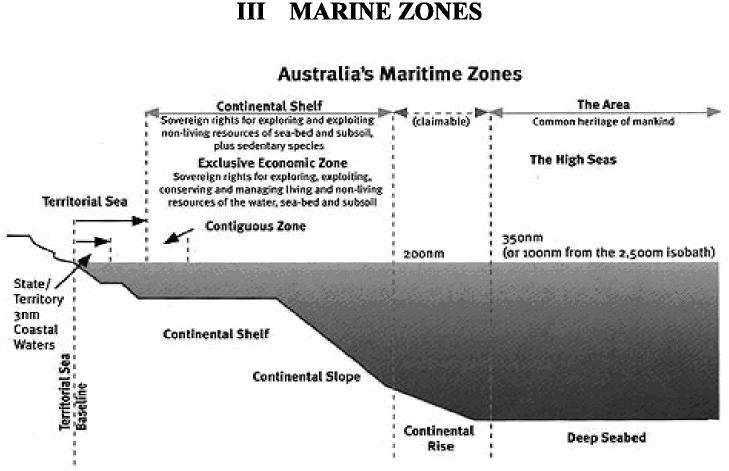

FIGURE 1: AUSTRALIA’S MARITIME ZONES[41]

In late 1994, Australia ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (‘UNCLOS’)[42] . A number of maritime zones are defined under UNCLOS according to their distance from a State’s Baseline. The maritime zones that Australia implements and enforces in accordance with UNCLOS that are relevant to this paper are: Coastal Waters; Territorial Seas; Contiguous Zone; and the Exclusive Economic Zone.[43]

The Australian states and the Northern Territory in agreement with the Commonwealth, pursuant to s 5 1(xxxviii) of the Constitution, have jurisdictional rights over the water column and subjacent seabed to 3 nautical miles from the baseline.[44] The waters inland from the Baseline remain the jurisdiction of the States or Northern Territory.[45] However, the jurisdiction for the employment of ADF assets in both areas is the same. Internal and coastal waters are considered territorial seas.[46] The jurisdiction of the area is relevant to the use of ADF boarding parties to enforce counter-terrorism and security for ships and vessels that are in port.

UNCLOS article 2 establishes the extension of a State’s sovereignty to the territorial sea, air space, sea bed and subsoil.[47] UNCLOS article 3 sets the limit of the territorial sea from the baseline out to 12 nautical miles.[48]

UNCLOS article 27 establishes the general rule that a state’s criminal jurisdiction on foreign ships should not be exercised but provides exceptions to this rule as follows:

(a) if the consequences of the crime extend to the coastal State;

(b) if the crime is of a kind to disturb the peace of the country or the good order of the territorial sea;

(c) if the assistance of the local authorities has been requested by the master of the ship or by a diplomatic agent or consular officer of the flag State; or

(d) if such measures are necessary for the suppression of illicit traffic in narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances.

Article 27(2) UNCLOS provides a further exception that article 27 does not ‘affect the rights of the coastal State to take any steps authorised by its laws for the purpose of an arrest or investigation on board a foreign ship passing through the territorial sea after leaving internal waters’. It would appear that the inner adjacent area defined in the CaSA reflects the position under UNCLOS article 27. However, instead of a State’s criminal jurisdiction operating by exception as under UNCLOS, the State’s criminal jurisdiction under CaSA operates as a general rule.

An example of employment of ADF assets to enforce Commonwealth laws in the Territorial Sea was the Australian Federal Police (AFP) Operation Sorbet.[49] In late March 2003, the vessel Pong Su had sailed from North Korea to Singapore, down the coast of Western Australia, then east along the Australian coastline to Victoria. At the coastline near the Victorian town of Lorne, crewmen disembarked with a cache of heroin. The Pong Su originally brought itself to the attention of the authorities when it failed to declare its presence in Australian waters and then refused to stop.[50] The Pong Su, by these actions, heightened national security sensitivities and was initially thought to be conducting people smuggling activities. ADF assistance was requested by the AFP and resulted in the interdiction of the Pong Su by HMAS Stuart with elements of the Special Forces boarding her.

UNCLOS article 33 provides a further zone between 12 nautical miles to 24 nautical miles from the baseline for Australia to exercise control over to prevent or punish infringements of customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary regulations within its territory or territorial sea. Various Australian legislation appoints ADF personnel as ‘authorised officers’[51] to effect ‘customs, fiscal, immigration and sanitary law’.[52] The practical application of the Contiguous Zone is that it allows Australia more time to organise an interdiction of identified vessels breaching Australian laws. For example, along the coastline of Northern Australia, this zone allows for a time and space ‘buffer’ so that interception may be made of suspect vessels before they are able to effect landfall.

UNCLOS article 55 provides for the legal regime of the Exclusive Economic

Zone (‘EEZ’) and the Australian Fishing Zone (‘AFZ’)[53] which covers the area

between 12 nautical miles and 200 nautical miles from the baseline.[54] The EEZ extends the coastal State’s sovereign rights with regards to conserving and managing the natural maritime resource, both living and non-living. This also includes the jurisdiction over artificial islands, installations and structures, marine scientific research and protection and preservation of the marine environment. The AFZ was a precursor to the EEZ. However, it has been retained for the purposes of fisheries management through the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (‘AFMA’) and Fishing Industry Policy Council.[55] The enforcement of Australian sovereignty in the EEZ (and hence the AFZ) can be illustrated by the various apprehensions or pursuits involving Commonwealth agencies and assisted by the ADF. Examples include the pursuit of the fishing vessels Viarsa, South Tomi, Lena, Volga and Maya V, all cases of illegal fishing taking place in the EEZ/AFZ adjacent to HIMI. These recent naval operations have demonstrated a marked increase in the use of boarding parties.

Those waters that are not Australian territorial seas, contiguous zones or EEZ comprise the High Seas. The High Seas are ‘open waters’ and States are free to navigate these waters for peaceful purposes. No State can exercise jurisdiction over any ships of other States, interfere with or detain them, unless under the doctrine of hot pursuit.[56] Unless the suspect vessel is an Australian flag vessel, hot pursuit may be commenced whilst the suspect vessel is within the Territorial Sea, Contiguous Zone or EEZ.[57] Hot pursuit is a common occurrence for illegal fishing operations when the suspect vessel is attempting to escape or evade Australian authorities.[58] The rights bestowed by UNCLOS article 111 provide the primary jurisdiction for the ADF to board suspect vessels on the High Seas when conducting non-defence activities. However, it would appear that the CaSA widens the ability for Australia to board foreign vessels[59] which breach Australian criminal laws on the High Seas.

It is when ADF personnel are employed as boarding parties in the various maritime zones for non-defence purposes that they are subject to the possible jurisdiction of the CaSA.

On 1 November 1979 the Crimes at Sea Act 1979 (Cth) came into force.[60] It was an agreed scheme of complementary Commonwealth and State[61] legislation that would ensure ‘an appropriate body of Australian criminal laws – either State or Territory – [was] applicable to ships and to activities in offshore areas coming under Australian jurisdiction’.[62] State legislation under the scheme dealt with ‘offences in the territorial sea and offences committed on voyages between two ports in one State, or [voyages] that began or ended at the same port in a State’.[63] During the Premiers Conference on 29 June 1979, the Commonwealth and States agreed that the territorial sea would only be of 3 nautical miles breadth.[64] The Crimes at Sea Act 1979 (Cth) applied to offences:

committed on Australian ships which are on overseas, inter-state or Territory voyages. The Act also applies to offences on Australian ships in foreign ports, offences by Australian citizens on foreign ships where they are not members of the crew, and offences in offshore areas outside the territorial sea in relation to matters within Australian jurisdiction. In certain limited cases the Act can also be applied to offences committed on foreign ships.

Although the Crimes at Sea Act 1979 (Cth) applied to Australian ships and citizens and, in limited cases foreign ships its main limitation was that State jurisdiction extended only over the territorial sea up to 3 nautical miles.

The CaSA was assented to on 31 March 2000 but came into force on 31 March 2001[65] and stands at the head of a cooperative scheme of legislation enacted[66] in each Australian State and the Northern Territory.[67] The CaSA establishes the application of substantive criminal law[68] of either the State, Northern Territory or Commonwealth to defined areas.[69] To date, there has been only one case that has noted the application of the CaSA: Blunden v Commonwealth of Australia.[70] Justice Kirby noted that, although the provisions of the CaSA did not apply to the matter, ‘they demonstrate the fact that, where there is a will, the Federal Parliament can enact specific laws governing the consequences under Australian municipal law of events having an Australia connection although actually occurring on the High Seas, that is, in international waters’.[71] However, there has been no publication[72] on the extent of the implementation of the CaSA with respect to incidents involving ADF personnel.

The CaSA legislates the application of States’ criminal jurisdiction[73] to the area on the landward side of the baseline and the area from the baseline up to 12 nautical miles.[74] The CaSA refers to this as the ‘inner adjacent area’.[75] The area from 12 nautical miles up to 200 nautical miles[76] adjacent to the particular State, by force of Commonwealth law, also applies the criminal jurisdiction of the particular State. The CaSA refers to this as the ‘outer adjacent area’.[77] Both areas combined are referred to as the ‘Adjacent area’ to a particular State.[78] See the indicative map from Appendix 1 of the CaSA for an illustration of the area.[79]

Parts 1–4 of the CaSA stipulate the conditions to which Commonwealth laws will apply to criminal acts pursuant to incidental power under s 51 (xxxix) of the Constitution. Schedule 1 of the CaSA establishes the legislative and administrative grounding of the co-operative scheme agreed to by the Commonwealth and the States for enactment by the States.[80] The first half of the CaSA deals with the application of Commonwealth laws in the Adjacent area and beyond. Schedule 1 deals with the operation of the State criminal jurisdiction in the Adjacent area only.

There are two very detailed definitions in the CaSA: ‘law of criminal investigations, procedure and evidence’[81] and ‘substantive criminal law’.[82] Both definitions include the written and unwritten[83] laws and any interpretations regarding the defined phrase. It is interesting to see a common legal understanding legislated in such a way. However, by defining these two phrases, any requirement to specify the numerous pieces of legislation, cases and court procedure has been removed. It also potentially provides some clarity as to the extent of the phrases. However, only time will tell whether this attempt to ‘cover the field’ is effective.

Schedule 1 of the CaSA sets out the co-operative scheme which was enacted by the States in separate legislation.[84] The substantive criminal laws of the States apply throughout the Adjacent area.[85]

The ‘area of administrative responsibility’ for a particular State is defined to include:

(a) the area of the State; and

(b) the inner adjacent area for the State; and

(c) other parts of the adjacent area in which the State has, under the intergovernmental agreement, responsibility (which may be either exclusive or concurrent) for administering criminal justice.[86]

The States’ criminal laws are limited in two ways. Firstly, to the extent that they are incapable of applying in the Adjacent area or are limited by express terms.[87] Secondly, to the extent that a State law has no legal effect in the Adjacent area.[88] Commonwealth laws apply to the investigation, procedures and acts done by a Commonwealth authority. State laws apply similarly to State authorities exercising jurisdiction within the State’s Area of Administrative Responsibility. Further, the CaSA stipulates that in any Commonwealth or State judicial proceeding,[89] the authorities will use their respective Commonwealth or State Laws regardless of whether the maritime offence is a State or Commonwealth offence or where the offence took place in the Adjacent area.[90]

Interestingly, sch 1, cl 3(3) specifies that the application of laws set out in cl 3 are to prevail over any State or Commonwealth laws that are inconsistent with it. On first glance this appears to override s 109 of the Constitution. However, the co-operative scheme was a joint States, Territory and Commonwealth agreement, enacted under s 5 1(xxxix) of the Constitution. Although sch 1 sets out the law to be enacted by the State, it is an enactment of a Federal law and therefore not in contravention of s 109 of the Constitution.

Schedule 1, cl 4 provides that in a proceeding for a maritime offence under State criminal laws, all that is required to be proved is the location of the alleged act or omission. This requirement can be proved through an allegation in information or a complaint if there is no other evidence available. The presumption created by sch 1, cl 4 has the affect of strengthening the substance of a complaint or information without any other evidence. This assumption apparently prevails even where only the defendant ‘is in a position to accurately identify’ the conduct’s location.[91] However, this assumption is unlikely to be used in practice as general ADF boarding party procedure requires location to be determined prior to conducting the boarding.[92]

One question that is raised regarding this is: what kind of ‘evidentiary proof’ is required to rebut this presumption? Further, the standard required to rebut may be different in a State judicial proceeding using State criminal laws than if in a Commonwealth judicial proceeding. For example, under Commonwealth criminal laws, the Criminal Code Act 2002 (Cth) (‘Criminal Code’) is applicable. Section 58 of the Criminal Code establishes the evidentiary burden of proof. Section 59 of the Criminal Code stipulates that a legal burden of proof[93] is only imposed on a defendant if it is expressly stipulated or there is a presumption that the burden applies. In this matter, without any express stipulation or presumption, it would appear that under the Criminal Code, to rebut the presumption under cl 4, the defendant has an evidentiary burden.[94]

The CaSA ensures that the States may charge individuals for a maritime offence within the Adjacent area. However, the Commonwealth Attorney-General’s consent is required in circumstances where the offence is alleged to have been committed on or from a foreign, and the ship is not an Australian registered ship, and the county of registration would have jurisdiction under international law.[95] Prior to granting consent, the Commonwealth Attorney-General will take into account the view of the country of registration.[96] However, any delay in granting consent will not prevent or delay arrest of the alleged offender, laying of charges, extradition proceedings or remand proceedings.[97] If the Attorney-General’s consent is refused, then the proceedings are permanently stayed.[98]

Parts 1–4 of CaSA legislates the application of the substantive criminal law of the Jervis Bay Territory to the sea outside the Adjacent area.[99] The law of the Jervis Bay Territory applies to criminal acts outside the Adjacent area[100] in the following three situations:[101]

1. Australian Ship

on an Australian ship[102] ; or in the course of activities controlled from an Australian ship;[103] or a person who has abandoned, or temporarily left, an Australian ship and has not returned to land;[104]

2. Australian Citizen

(other than a member of the crew) on a foreign ship[105] or in the course of activities controlled from a foreign ship[106] ; or who has abandoned, or temporarily left, a foreign ship and has not returned to land[107] ; and

3. Foreign Ship

on a foreign ship[108] or in the course of activities controlled from a foreign ship[109] ; of a person who has abandoned or temporarily left a foreign ship and has not returned to land, if the first country at which the foreign ship calls, or the person lands, after the criminal act, is Australia or an external territory of Australia.[110]

Through the external affairs power under the Constitution,[111] if the conditions stipulated in s 6 of the CaSA are met, the CaSA applies to criminal acts allegedly committed on the High Seas and potentially in other countries’ waters. A further interesting point is that the CaSA also has a primary enforcement jurisdiction for criminal conduct on or from a Defence Force ship as such vessels are included in the definition of an ‘Australian ship’.[112] Therefore, the jurisdictional scope of the CaSA is wide, in that, it could apply to anywhere on the ocean as long as the conditions in s 6 are met.

As mentioned above, proceedings involving an offence occurring outside the Adjacent area require the Attorney-General’s consent before any charge can proceed to hearing or determination.[113] If it is an indictable offence, then the charge cannot proceed to preliminary examination in committal proceedings without the Attorney-General’s consent.[114] Further, the Attorney-General must take ‘into account any views expressed by the government of a country other than Australia whose jurisdiction over the alleged offence is recognised under principles of international law’.[115] If there is another country’s jurisdiction in issue, the CaSA provides that it is a defence for the accused to prove that:

No corresponding offence exists under the law of the other country; or [s]uch a corresponding offence does exist but a defence to a charge of the corresponding offence could be made out under the law of the other country.[116]

Similar to the State exercise of jurisdiction in the Adjacent area, any delay in granting consent does not consequentially delay arrest, laying of charges, extradition proceedings or remand proceedings.[117] Also, refusal of consent results in a permanent stay of proceedings.[118]

There are certain areas were the CaSA does not apply. An act to which s 15 of the Crimes (Aviation) Act 1991 (Cth) applies is excluded from the jurisdiction of the CaSA.[119] Further, s 6(10) specifies the exclusion of the territorial waters of Norfolk Island[120] and the coastal seas of Australian external Territories including: Christmas Island,[121] Cocos (Keeling) Islands,[122] Australian Antarctic Territory, Heard and McDonald Islands, Ashmore and Cartier Islands and the Coral Sea Islands.[123] These excluded areas are important to note, especially considering Commonwealth authorities, such as Customs, have been engaged in boarding parties within these areas for fisheries violations. The CaSA does not itself specify what laws apply in these excluded areas. However, the explanatory memoranda tabled during the second reading speech states that sub-s (10) ‘preserves the existing legal regime in the coastal waters of Australia’s external Territories’. Therefore, the CaSA does not affect the criminal law that currently applies in the territorial seas of Norfolk Island[124] and the external Territories.

Another excluded area from the application of the CaSA is the Joint Petroleum Development Area (‘JPD Area’). In the JPD Area the substantive criminal laws of the Northern Territory are applied.[125] There are also several circumstances where acts are excluded from the application of the CaSA. Acts done on or from a ship or aircraft, or acts by East Timorese nationals or residents who are not also nationals of Australia are also excluded.[126] The most common offences committed in the JPD Area by East Timor nationals are fishing offences. It would appear that excluding acts from ships and aircrafts limited the application of NT criminal laws[127] to oil platforms that are located within the JPD Area. Further, the CaSA also recognises the principle of double jeopardy by excluding an accused being charged if criminal proceedings were undertaken in East Timor.[128]

With no other publication or cases to assist in a working application and interpretation of the CaSA, one must rely on the text of the CaSA. An analysis of the application of the CaSA has been simplified into the following table:

|

|

Inner & Outer Adjacent area

|

Outside Adjacent area

|

|

Law of criminal

investigation,

procedure and

evidence

|

State criminal laws

Jurisdiction:

~ as a right in Inner Adjacent area

~ by force of Cth laws in Outer Adjacent area

Limitations:

~ Cth AG consent for any conduct including

indictable offence if;

o conduct on or from foreign ship;

o ship registered in non-Aus country;

o Country of registration has jurisdiction

over conduct under international law.

Exclusions:

• Constitution invokes Cth Jurisdiction

• Excluded external Territories laws -cl 9

• JPD Area – cl 10

|

Commonwealth criminal laws

Limitations:

• Australian ship;

• Australian citizen on foreign ship

• foreign ship If 1st country is Australian

– s 6

Conditions:

• AG Consent – ss 6(4)–(5)

• Non-Australian Country jurisdiction

– s 6(9)

Exclusions:

• Excluded external Territories

– s 6(10).

• JPD Area – Part 3A

|

|

Substantive

criminal law

|

State criminal laws

See State Jurisdiction, Limitations & Exclusions

above

Exceptions:

• Laws incapable of applying or expressly

limited: ie driving car offences - sch 1 cl

2(3);

• No legal effect: ie Conflict with Cth laws re

s 109 Const itut ion – sch 1 cl 2(4)

|

Commonwealth criminal laws

See Cth Limitations, Conditions &

Exclusions above.

|

|

Cth judicial

proceeding

|

Commonwealth criminal laws

Constitution gives Cth jurisdiction: ie Fisheries

or Customs.

See Cth Conditions & Exclusions above.

|

Commonwealth criminal laws

See Cth Limitations, Conditions &

Exclusions above.

|

|

State judicial

proceeding

|

State criminal laws

See State Jurisdiction & Limitations above

Assumption:

• If act found to occur in another State, State

whom initiated proceedings first continues

under its own laws - Sch 1 cl 3(2)

See State Exclusions above.

|

No State jurisdiction

|

FIGURE 2: APPLICATION OF JURISDICTION FOR CRIMES AT SEA.

Because the definition of an ‘Australian ship’ includes ships belonging to an ‘arm of the Defence Force’, the conduct of ADF personnel while performing tasks as part of a boarding party is not exempt from the provisions of the CaSA. Therefore, depending on the location of the alleged conduct that breaches criminal law, ADF personnel will be subject to the civilian criminal laws of the relevant State or the Commonwealth. The issue is how far the recent Alpert case has changed the way the ADF determines jurisdiction between civilian criminal law and the DFDA.

The Australian Government has used the ADF to conduct boardings to enforce the laws of the Commonwealth for some time. In 1991, and then in 1997, the Parliament of Australia conducted an ‘examination of the legal basis for Australian Defence Force involvement in ‘non-defence’ matters’.[129] The paper concluded that ‘Constitutional lawyers agree that the Commonwealth can use the defence force to enforce its laws and protects its interests and property’.[130] Therefore, the power of the Commonwealth to legislate in matters regarding the ADF is wide.

Section 51 of the Constitution, with respect to the ADF,[131] provides:

The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to: (vi) the naval and military defence of the Commonwealth and of the several States, and the control of the forces to execute and maintain the laws of the Commonwealth.

The defence power has been described as a ‘purposive’[132] power in that it seems to ‘treat defence or war as the purpose to which legislation must be addressed’.[133] The power also expands in times of war and contracts in times of peace.[134] The defence power has been described as having two purposes or limbs:[135]

First limb: the naval and military defence of the Commonwealth and of the several States; and

Second limb: the control of the forces to execute and maintain the laws of the Commonwealth

In Re Tracey, these two limbs are seen as having distinct and separate purposes:[136] The first dealing with defence or the military and the second relating ‘to the work of law enforcement’[137] that ‘is not the ordinary function of the armed services to ‘execute and maintain the laws of the Commonwealth’.[138] Nothing further of substance was added to the discussion of the second limb in the second and third High Court cases considering the jurisdiction of the DFDA.[139] In Alpert,[140] the most recent DFDA jurisdictional case, Gummow J reiterated the interpretation in Re Tracey of the second limb. However, despite non-defence activities not being the ‘ordinary function’ of the ADF, these activities are nonetheless undertaken.

The use of ADF under the second limb of s 51 (vi) was previously considered in Li Chia Hsing v Rankin.[141] The case considered the legality of an interdiction undertaken by a Naval Officer commanding HMAS Aware about 10 nautical miles from the baseline in the Gulf of Carpentaria. The Court upheld the employment of ADF personnel in the enforcement of the laws of the Commonwealth.[142]

The ADF provides non-military law enforcement or ‘aid to the civil power’ in three ways. Firstly, aid to the Commonwealth or Territory Authorities for law enforcement tasks, such as protection of Commonwealth interests.[143] Secondly, aid to State authorities for law enforcement tasks, such as surveillance and detection of criminals.[144] Lastly, execution and maintenance of certain statues of the Commonwealth, such as aiding customs or fisheries agencies.[145] The first two situations deal with aid within Australia and require the imposition of certain legislated procedures before the ADF can be ‘called out’.[146] However, it is the last situation that utilises ADF assets for internal and external aid and requires no specific procedure other than that ADF personnel be stipulated as ‘authorised officers’ under the various Commonwealth laws that allow the Commonwealth to employ the ADF expeditiously.

The use of ADF under the second limb of s 51 (vi) was previously considered in Li Chia Hsing v Rankin.[147] The case considered the legality of an interdiction undertaken by a Naval Officer commanding HMAS Aware about 10 nautical miles from the baseline in the Gulf of Carpentaria. The complainant Master and his boat were observed in the declared fishing zone with ‘equipment for taking, catching and capturing fish’.[148] The Master and boat were arrested by the Naval Officer under the provisions of the Fisheries Act 1952 (Cth). The High Court dismissed the applicant’s ‘no case to answer’ application.

The applicant had submitted that the Naval Officer was not an ‘authorised officer’ under the Act. It was argued that it was ‘beyond the legislative competence of the Commonwealth’ to utilise ADF personnel for the purposes of civil arrest. Alternatively, the ADF ‘officer was not specifically authorised’ to exercise the powers by virtue of the Defence Act 1903 (Cth) or Naval Defence Act 1910 (Cth) which limited ADF operations or aid to civil authority to suppress riots.[149]

An unanimous Court agreed with Barwick CJ and declared ‘no substance’ to the applicant’s submissions regarding the illegality of the ADF officer’s actions, saying: ‘[t]here is no constitutional objection to the employment of a member of the defence forces in the performance of acts in furtherance of the provisions of the Fisheries Act…’.[150] Justice Gibbs went further by stating that ‘[t]here is no constitutional reason why an officer of the naval forces should not assist in the enforcement of a law of the Commonwealth such as the Fisheries Act’.[151] This case affirmed that using the ADF for ‘non-defence’ activities was not an abuse of the defence power under s 51 (vi) of the Constitution and thereby solidified the Government deployment of ADF assets for this task.[152]

Until the MV Tampa incident in August 2001, the use of ADF assets had not been the focus of consistent media attention. The Tampa incident again raised the issue of the government’s use of ADF assets to enforce its laws. The judgement in Ruddock v Vadarlis[153] did not question whether the use of ADF assets (in this case SASR troops) was an abuse of the second limb of the defence power.[154] However, the case and the consequences of the Tampa incident ensured that the deployment of ADF assets to enforce Commonwealth laws was and continues to be a topic of public discussion.

This focus on the conduct of ADF boarding parties to ‘execute and maintain the laws of the Commonwealth’ was again recently questioned by a case involving the apprehension of the fishing vessel Volga in February 2002.[155] The Volga was apprehended and boarded by RAN personnel for fishing in Australia’s EEZ adjacent to HIMI in breach of the Fisheries Management Act 1991 (Cth).[156] The owners of the Volga submitted that the vessel was not properly forfeited under the Act as there had been no conviction for any of the Act’s offences prior to apprehension. Alternatively, the Act was unconstitutional on grounds that it ‘violated the separation of powers under Ch III’ of the Constitution, in that the ‘provisions were beyond the powers of the Commonwealth’ and that the Act ‘effected an acquisition of property other than on just terms’.[157] Justice French determined that there was no infringement of the judicial or executive power by the Fisheries Management Act 1991 (Cth) and further held that the forfeiture of the vessel was automatic upon commission of one of the ‘qualifying offences’ under the Act.[158] The senior crewmen of the Volga also challenged the validity of the Act and sought a permanent stay of proceedings on the basis that the boarding was unlawful due to breaches of international law regarding hot pursuit (UNCLOS art 111) and that the provisions of the Act were beyond the powers of the Commonwealth.[159] This application was also rejected. The issue regarding hot pursuit will not be further discussed in this paper.

In light of the judgments involving the Volga, the validity of the Commonwealth using ADF assets has solidified and therefore, the trend towards use of ADF boarding parties will only continue and possibly increase. In light of this trend, the effects of the jurisdiction of the CaSA on ADF personnel is heightened.

Section 51(vi) of the Constitution does not specifically provide for the discipline of the naval and military defence of the Commonwealth. However, it was discussed by Mason CJ, Wilson & Dawson JJ in Re Tracey that:

Although the Australian Constitution does not expressly provide for disciplining the defence forces, so much is necessarily comprehended by the first part of s 51 (vi) for the reason that the naval and military defence of the Commonwealth demands the provision of a disciplined force or forces.[160]

It was noted in Alpert that the first limb of s 51 of the Constitution ‘authorised the making of the DFDA ’.[161] Further, the first limb has also been relied upon to support the validity of the DFDA ’s jurisdiction and extra-territorial operation.[162]

The DFDA applies to conduct of defence members. Its jurisdiction relies directly on whether or not the person is a member of the ADF. A determination of the application of the DFDA to members of the ADF Reserve Forces is focused on whether or not they are ‘acting or purporting to act in the capacity as a member’.[163] Therefore, the DFDA applies to all ADF members based on their membership of the ADF.

Prior to 2003, the issue of the jurisdictional validity of service tribunals for events occurring in Australia was before the High Court on five occasions. Two cases, in 1942 and 1945,[164] involved the interpretation of military discipline prior to the enactment of the DFDA. In the trilogy of DFDA Jurisdictional cases between 1989 and 1994 (Re Tracey,[165] Re Nolan[166] and Re Tyler[167] ), the High Court upheld the constitutional validity of the exercise of military jurisdiction. The conduct charged in these three cases was inherently criminal in character and involved, inter alia, offences of dishonesty. In each instance the Court was concerned with the constitutional validity of the exercise of the military jurisdiction under the Constitution which potentially impacted on the exercise of State criminal jurisdictions.

This paper will not discuss in detail the ‘divergence of opinion’[168] between the judgments in Re Tracey. However, the test applied by Brennan and Toohey JJ has become the common test when determining the jurisdiction of the DFDA. That test is commonly referred to as the ‘service connection’ test and states that:

proceedings may be brought against a defence member or a defence civilian for a service offence, if but only if, those proceedings can reasonably be regarded as substantially serving the purpose of maintaining or enforcing service discipline.[169]

Alpert was the first High Court case to deal with the jurisdiction of the DFDA outside of Australia.[170] In a decision of 4:3 majority, the High Court held that the conduct of a member on overseas service, despite being on leave,[171] was within the jurisdiction of the DFDA. The member was charged with an offence of rape,[172] which in accordance with the ADF Instruction[173] and the DFDA, is a charge that is generally referred to civilian agencies for prosecution. Alpert, therefore, potentially extended the jurisdiction of the DFDA to offences committed overseas during the period the member is deployed, including any leave time.

It would appear that at its broadest application, factors arising from Alpert have widened the service connection test to be, in reality, a service status test. The Supreme Court of the United States returned to a Service Status test in 1987 after 18 years using a ‘service connection’ test.[174] By Solorio v United States[175] rejecting the ‘service connection’ test, members of the Armed Forces could be charged with any offence on the basis that they were a member of the military. Therefore, as raised by Kirby J in Alpert, the jurisdiction of the DFDA has expanded and ‘represents an attempt to move away from a “service connected” approach to one of “service status”’.[176] In Re Tracey, the court discussed the definition of a service offence. Two schools of thought emerged through the trilogy of cases prior to Alpert. Firstly, that there were only offences of a military character or civil nature.[177] Secondly, that there were three types of offences: military in character, civilian in nature and a hybrid of the two.[178] In Alpert the court was again divided into these two schools of thought.[179] The majority, lead by Mason CJ, agreed that you cannot ‘draw a clear and satisfactory line’ between the two types of offences.[180] The strong dissenting judgment of Kirby J in Alpert warned that the extension of jurisdiction into ‘non-service related’[181] offences, including that of rape, was ‘pushing the boundary of service discipline beyond its constitutional limits’[182] and ‘would effectively render the requirements of connection to some aspect of national “defence” meaningless’[183] . Kirby’s discussion regarding the three types of offences raises another potential issue. When determining the juxtaposition of the DFDA and CaSA, is the factor that the alleged offence occurred while conducting a non-defence activity relevant?

The CaSA was enacted to provide a national uniform scheme in cooperation with the States and the Northern Territory. The CaSA has jurisdiction over ADF ships operating in and beyond the Adjacent area, namely beyond 200 nautical miles of the Australian baseline.

In today’s environment, the Commonwealth of Australia is employing ADF assets to assist it to ‘execute and maintain’ its laws. Although this is not an ‘ordinary function’ of the ADF, it is becoming common. ADF personnel have been employed to conduct boarding parties and in undertaking these tasks are exposed to the jurisdiction of both civilian criminal law and the military disciplinary code.

The CaSA applies to ADF personnel every time they are deployed to sea. This jurisdiction extends not only to the conduct of boarding parties on civilian ships but also to conduct on board ADF ships. The DFDA applies to defence members either in or outside Australia. Therefore, there are two sets of criminal laws that apply to ADF personnel when they are deployed to sea: one civilian and one military. A third set of civilian laws relevant to the application of the CaSA are those from other countries.

In most cases, the jurisdiction of the DFDA applies prima facie to the conduct of ADF personnel. However, the test for jurisdictional application is an exception to the general rule: DFDA will only apply if there is sufficient service connection. The creation of the DFDA relied on the first limb of s 51 (vi) of the Constitution which has been described as dealing with defence.[184] The second limb of s 5 1(vi) has been described as non-military in that it relates to ‘law enforcement’. Specifically, by being deployed on non-military activities, does the deployment enliven the debate about whether or not the DFDA applies as the purpose of the deployment is to ‘execute and maintain the laws of the Commonwealth’ and not the ‘naval or military defence of the Commonwealth’? Therefore, if ADF personnel are conducting boarding parties for a non-defence activity, is the DFDA still applicable to their actions? One could argue that as the non-defence activities are not in the furtherance of defence, then the DFDA does not apply for the duration that ADF are engaged in non-defence activities. A more practical view is that whenever a member of the ADF is tasked to perform a duty as a member of the ADF, the DFDA has jurisdiction over him for the duration of that task.

Membership of the ADF is defined in s 3 of the DFDA and is critical to the argument of the jurisdiction of the DFDA. The definition does not focus on the activities that the person was undertaking. Even when jurisdiction over ADF reservists is in issue, the definition focuses on their status and not what activities or tasks they are undertaking. Therefore, it would appear that the practical view prevails in that when ADF members are engaged in non-defence activities, the DFDA would apply.

The jurisdiction of the DFDA undoubtedly covers ADF personnel in operations. However, the increase in the use of ADF boarding parties to enforce the Commonwealth suite of legislation against illegal immigrants and poachers has raised the existence of a conflict between civilian criminal laws and military discipline. Does one set of laws override the other? In the author’s opinion, this depends on the circumstances that the conduct occurs in with the location of the conduct, whether inside or outside 200 nautical miles, also being relevant. As a general rule, the CaSA applies as a primary source of law. The DFDA will only apply if there is a service connection. If there is a service connection, then due to prior agreements with the State and Commonwealth Directors of Public Prosecutions, ADF personnel can be charged under the DFDA instead of the CaSA.

The extent of the application of the DFDA has been widened by the recent High Court decision in Alpert. The existing ADF Instruction[185] to assist in the determination of the DFDA jurisdiction has potentially been rendered obsolete due to the widening of the factors used in Alpert to determine service connection. As there is no up to date ADF Instruction incorporating the factors considered in Alpert, although a redraft is currently being undertaken, factors relevant to determining the jurisdictional conflict between the CaSA and the DFDA could be overlooked by ADF Commanders. This may create some confusion regarding the applicability of the CaSA to ADF members.

As the CaSA is applicable to ADF ships and their personnel, any criminal act committed by ADF personnel anywhere within Australian waters, or any offence committed beyond the Commonwealth area, is covered. The process of determining which law applies is rendered simple by determining whether or not the conduct was committed within 200 nautical miles. Within 200 nautical miles, the State criminal law applies and it would then be the issue of whether or not there is sufficient service connection to raise the jurisdiction of the DFDA. If the conduct is committed outside 200 nautical miles from Australia’s baseline, then it would prima facie fall within the jurisdiction of the Commonwealth and the CaSA and then the question of nexus to raise DFDA jurisdiction must be asked.

However, there may exist the possibility of another country’s laws being applicable. If this were to occur, the Attorney-General would have to consider the views of that other country before consent could be granted to commence a hearing. In a practical sense, if the other country objected to Australia initiating proceedings for conduct committed inside the other country’s territorial waters, the Commonwealth may hand over the matter to the other country, in the interests of continued good relations. However, any involvement of another country’s laws becomes a very challenging matter if the accused is an ADF member on ADF operations.

Generally, a Status of Forces Agreement (‘SOFA’) between the ADF and another country would have been entered into prior to any commencement of ADF operations in foreign waters. According to the SOFA, if the other country’s jurisdiction would apply, then the matter would be handed over regardless of the CaSA. If the SOFA stipulated the matter fell within the Australian laws, then there would be a conflict between the application of the CaSA and the DFDA.

If an ADF boarding party member commits an offence outside 200 nautical miles area and both the CaSA and DFDA applied, what would be the process of determining jurisdiction? The determination of jurisdiction would depend on the nature of the offence. The range of possible offences that boarding parties may commit could be limitless. However, more common possibilities would be murder (if in breach of the rules of engagement), theft and assault.

Taking the murder example, CaSA makes it clear that such an offence committed by an ADF member would be within its jurisdiction if it occurred on an ADF ship or on a foreign ship, as the jurisdiction would fall within the application to an Australia ship under s 6(1) or possibly under s 6(2)(a) in that the ADF member is an Australian citizen on a foreign ship. Although s 63 of the DFDA stipulates that consent of the DPP is required before military proceedings could be instituted in cases of murder[186] , it is possible due to the expansive jurisdiction in Alpert,[187] that the same reasoning applied therein could allow a murder offence to be heard by a military tribunal, as long as there was sufficient service connection. In the case of a boarding party, if a murder offence was allegedly committed, then the factors that assist to determine the service connection test may be whether the member was on duty, conducting military operations, in uniform or with other ADF members present. Then arguably the DFDA could have jurisdiction if the DPP consents. However, if the offence occurs in another jurisdiction or the DPP decides not to proceed, then arguably, based on Alpert, the DFDA would have jurisdiction without the consent of the DPP.

In the case of theft or assault the factors to assist the determination of the service connection test would be the same as for the murder offence example above. The effects of Alpert would render the jurisdiction within the DFDA again. It appears that the concerns raised by Kirby J in Alpert could be an eventuality, in that, ‘virtually every serious criminal offence by service personnel’ would be classified as service connected.[188] However, despite the extremely wide application of the DFDA’s jurisdiction, there is still the application of DPP jurisdiction through s 63 of the DFDA. If at any time the DPP wished to initiate proceedings for an offence allegedly committed by an ADF member, then s 63 of the DFDA permits this. Although the consequences of Alpert is that it provides the DFDA with an expanded jurisdiction over serious criminal offences, the CaSA would still have the ‘primary enforcement responsibility for criminal conduct on or from a Defence Force ship’[189] for those offences the DPP chooses to prosecute (excluding those offences assumed by another country). However, this primary enforcement responsibility may lose some weight when the offence is military in character or, if committed outside of 200 nautical miles, is a summary offence and therefore perceived as not so serious. Only time will tell whether any dichotomy in the application of the CaSA and DFDA between serious and not so serious offences committed outside of 200 nautical miles will eventuate.

[*] LLB (QUT), Grad. Cert in Law (QUT), Grad. Dip in Military Law (Melb), BA (Monash). Solicitor and Legal Officer (Captain), Department of Defence – Army; postgraduate student, University of Melbourne. These views are my own and do not represent those of the Australian Defence Force. This paper is a revised dissertation submitted for Naval Operations Law at University of Queensland for the Master of Laws degree.

[1] See, eg, Australian Courts Act 1828 (Imp) 9 Geo IV, c 83; Admiralty Ofences (Colonial) Act 1849 (Imp) 12 & 13 Vict c 96; Butterworths, Halsbury’s Laws of Australia [2702220].

[2] R v Keyn (The Franconia) [1876] UKLawRpExch 73; (1876) 2 Ex D 63, 162 (Cockburn CJ). See also R v Anderson [1861–73] All ER Rep 999.

[3] Crimes at Sea Act 1998 (NSW); Crimes at Sea Act 2001 (QLD); Crimes at Sea Act 1998 (SA); Crimes at Sea Act 1999 (VIC); Crimes at Sea Act 1999 (TAS); Crimes at Sea Act 2000 (WA); Crimes at Sea Act 2000 (NT). There are no equivalent provisions in the Australian Capital Territory.

[4] Butterworths, above n 1, [2702225].

[5] To avoid confusion, only the Commonwealth CaSA will be referred to, although the States enacted their own CaSAs.

[6] Second Reading Speech, Crimes at Sea Bill 1999 (Cth), Legislative Council, 30 September 1999 (Dr Stone, Member for Murray).

[7] Defence Force Discipline Act 1985 (Cth) s 9.

[8] For an update of the DFDA since its enactment, see Hyder Gulam, ‘An Update on Military Discipline – the 20th Anniversary of the Defence Force Discipline Act’ (2004) Deakin Law Review 10.

[9] Defence Instruction (General) PERS 45-1, Jurisdiction under Defence Force Discipline Act – Guidance for Military Commanders (DI(G)PERS 45-1) promulgated at 17 February 1999.

[10] Whether or not a member is charged under the DFDA or the matter is referred to the DPP is an exercise of a Commander’s discretion. ADF Legal officers generally advise Commanders regarding the issues to assist the jurisdictional determination.

[11] [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 166 CLR 518.

[12] Re Tracey above n 11; Re Nolan and Anor; Ex parte Young [1991] HCA 29; (1991) 172 CLR 460; Re Tyler and Anor; Ex parte Foley [1994] HCA 25; (1994) 181 CLR 18; Re Colonel Aird; Ex parte Alpert (2004) 209 ALR 311. Prior to the enactment of the DFDA, the High Court also determined the jurisdiction of the Naval Discipline Act 1910 in R v Bevan; Ex parte Elias and Gordon [1942] HCA 12; (1942) 66 CLR 452 and the jurisdiction of the Defence Act 1903 (Cth) in R v Cox; Ex parte Smith [1945] HCA 18; (1945) 71 CLR 1.

[14] Ibid, [328]–[329].

[15] Although the Instruction is currently under review by the Directorate of Military Justice at the Defence Legal Division.

[16] See above n 12.

[17] Section 51 provides: ‘The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to: …(vi) the naval and military defence of the Commonwealth and of the several States, and the control of the forces to execute and maintain the laws of the Commonwealth.’

[18] There are several other Commonwealth laws that have been enacted and have the potential for ADF personnel to be involved in enforcement activities, but ADF personnel have not as yet been instructed by the Government. See, eg, Crimes (Foreign Incursions and Recruitment) Act 1978 (Cth); Protection of the Sea (Powers of Intervention) Act 1981 (Cth).

[19] Australian Fisheries Management Authority, Factsheet No 13 ‘Illegal Foreign Fishing’ <http://afma.gov.au/> at 23 March 2005.

[20] Such as ADF boarding parties and monitoring and communication assets.

[21] Michael White and Stephen Wright, ‘Australian Maritime Law Update: 2003’ (2004) 35 Journal of Maritime Law and Commerce 313, 323–324. See also below n 32.

[22] Justice Margaret White, ‘The Executive and the Military’ (Paper presented at the 8th Annual Public Law Weekend, Constitutional Law Weekend, Canberra, 7–9 November 2003) <http://law.anu.edu.au/cipl/2003conference.asp> at 4 April 2005. Ivan Shearer, ‘The Development of International Law with Respect to the Law Enforcement Roles of Navies and Coastguards in Peacetime’ in Schmitt and Green (eds), ‘The Law of Armed Conflict into the next Millennium’, US Naval War College International Study 71 (1998) 429

[23] Except for commentary: Butterworths above n 1, [270-2220 – 270-2260].

[24] This document holds a Restricted classification and cannot be referred to by name in the general public arena. It will be referred to as the ‘Doctrine’. See ‘Mission Complete’, Navy News <http://www.defence.gov.au/news/navynews/editions/4717/topstories/story20.htm> at 23 March 2005.

[25] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, opened for signature 10 December 1982, ATS 1994 31, art 2 (entered into force 16 November 1994).

[26] Whole ship activities refers to the extent of the effect that organising and deploying a boarding party has on the Ship. Members of the boarding party come from various working areas on the ship. Also the Ship undergoes a state of alertness during the deployment of a boarding party.

[27] ‘Mission Complete’, above n 24.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Australian Government: Department of Defence, ‘Current Overseas Operations’ <http://www.defence.gov.au/globalops.cfm> at 23 March 2005.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] This paper will not discuss the Tampa incident in detail, as the matter already has many publications devoted to it: Jean-Pierre L Fonteyne, ‘All Adrift in a Sea of Illegitimacy – International law perspective on Tampa Affair’ (2001) 12(4) Public Law Review 249; Paul Ames Fairall, ‘Asylum-Seekers and People Smuggling – From St Louis to the Tampa’ (2001) 8 James Cook University Law Review 18; Judith Gardam and Rosemary Owens ‘Border Protection Legislative Package – MV Tampa’s Removal comes under scrutiny’ (2001) 23(11) Law Society Bulletin (South Australia) 30; Michael Head, ‘The High Court and the Tampa Refugees’ (2002) 11(1) Grifiths Law Review 23; Philip Lynch and Paula O’Brien, ‘From Dehumanisation to Demonisation – MV Tampa and Denial of Humanity’ [2001] AltLawJl 86; (2001) 26(5) Alternative Law Journal 215; Geoffrey Lindell, ‘Reflections on the Tampa affair’ (2001) 4(2) Constitution Law & Policy Review 21; Tara Magner, ‘A less than ‘Pacific’ Solution for Asylum Seekers in Australia’ (2004) 16 International Journal of Refugee Law 53; Ryszard Piotrowicz, ‘The Case of MV Tampa: State and Refugee Rights collide at sea’ (2002) 76(1) Australian Law Journal 12; Steven Rares SC, ‘The independent bar and human right’ (2005) Australian Business Review 11; Don Rothwell, ‘The law of the sea and the MV Tampa Incident: Reconciling Maritime Principles with Coastal Sovereignty’ (2002) 13 Public Law Review 118; Graham Thorn, ‘Human Rights, Refugees and the MV Tampa Crisis’ (2002) 13(2) Public Law Review 110; Martin Tsamenyi and Chris Rahman (eds), ‘Protecting Australia’s Maritime Borders: The MV Tampa and Beyond’ Wollongong Papers on Maritime Policy No 13 (2002); Public Law Review: The Tampa Issue (2002) 13(2); Michael White, ‘MV Tampa Incident and Australia’s Obligations’ [2002] MarStudies 2; (2002) 122 Maritime Studies 7; Michael White, ‘Tampa Incident: Shipping, International and Maritime legal issues’ (2004) 78(2) Australian Law Journal 101; Michael White, ‘Tampa Incident: Some subsequent legal issues’ (2004) 78(4) Australian Law Journal 249; Mr Justice PW Young, ‘Arrest on the ‘Tampa’: Whether lawful – case note; R v Disun’ (2004) 78(1) Australian Law Journal 23; Frank Brennan, Tampering with Asylum: A Universal Humanitarian Problem (2003); Julietta Jameson, Christmas Island: Indian Ocean (2001); David Marr and Marion Wilkinson, Dark Victory (2003).

[33] Department of Defence website on ‘Current Overseas Operations’, above n 29.

[34] See Cox (in her capacity as Director of the Northern Territory Legal Aid Commission) v Minister for Immigration and Mu lticultural and Indigenous Afairs and Others [2003] NTSC 111; (2003) 179 FLR 474.

[35] Australian Government: Department of Defence, ‘Current Overseas Operations’, above n 29.

[36] Joint Statement, Senator Ian Macdonald, Senator Chris Ellison and Dr Sharman Stone, ‘Dangerous ice pursuit of Viarsa now longest in Australian maritime history’ (Press Release, 25 August 2003) <http://www.customs.gov.au/site/page.cfm?u=4232 & print=1 & C=3788> at 10 April 2005; Joint Statement, Senator Ian Macdonald and Wilson Tuckey, ‘South Tomi goes from villain to hero’ (Press Release, 18 September 2004) <http://www.mffc.gov.au/releases/2003/04199mj.html> at 10 April 2005; Senator Ian Macdonald, ‘Illegal fishing boat soon to become dive wreck off WA’ (Press Release, 13 April 2003) <http://www.mffc.gov.au/releases/2003/03058mj.html> at 10 April 2005. See also ‘Southern Ocean Operations – Viarsa chase’, Operational Updates (19 August 2003 – 3 October 2003) <http://www.customs.gov.au/site/page.cfm?u=4691 & print=1> at 10 April 2005.

[37] Joint Statement, Senator Ian Macdonald, Senator Chris Ellison and Dr Sharman Stone, ‘Viarsa is boarded’ (Press Release, 28 August 2003) <http://www.mffc.gov.au/releases/2003/03171mj.html> at 10 April 2005.

[38] Joint Statement, Senator Ian Macdonald, Senator Chris Ellison and Senator Robert Hill, ‘Navy to bring Viarsa 1 home’ (Press Release, 31 August 2003) <http://www.mffc.gov.au/releases/2003/03175mj.html> at 10 April 2005.

[39] Joint Statement, Senator Ian Macdonald and Senator Robert Hill, ‘Navy catches suspected Illegal Fishing Vessel’ (Press Release, 24 January 2004) <http://www.mffc.gov.au/releases/2004/04015mj.html> at 10 April 2005.

[40] Maya V senior officers were fined A$30 000 each and 37 crew members were fined A$1000 plus a five year good behaviour bond each for breaches of the Fisheries Management Act 1991 (Cth). See Senator Ian Macdonald, ‘Penalties given to Maya V crew’ (Press Release, 1 April 2004) <http://www.mffc.gov.au/releases/2004/04052m.html> at 10 April 2005; Senator Ian Macdonald, ‘Maya V crew penalties’ (Press Release, 24 August 2004) <http://www.mffc.gov.au/releases/2004/04178m.html> at 10 April 2005; Senator Ian Macdonald, ‘Maya V Convictions’ (Press Release, 9 September 2004) <http://www.mffc.gov.au/releases/2004/04195m.html> at 10 April 2005.

[41] Courtesy of National Oceans Office. See <http://www.oceans.gov.au/content_policy_v1/default.jsp> at 6 September 2005.

[42] UNCLOS, opened for signature 10 December 1982, 1994 ATS 31, art 2 (entered into force 16 November 1994).

[43] Australia also enforces its rights regarding its Continental Shelf. However, for the purpose of this paper, it has not been mentioned in detail.

[44] Coastal Waters (State Powers) Act 1980 (Cth); Coastal Waters (Northern Territory) Act 1980 (Cth); Australian Government, Geoscience Australia, ‘Maritime Boundary Definitions’ <http://www.ga.gov.au/nmd/mapping/marbound/bndrs.htm> at 23 March 2005. UNCLOS, opened for signature 10 December 1982, 1994 ATS 1994 31, art 7 (entered into force 16 November 1994).

[45] Coastal Waters (State Powers) Act 1980 (Cth) s 5; Coastal Waters (Northern Territory) Act 1980 (Cth) s 5.

[46] UNCLOS, opened for signature 10 December 1982, 1994 ATS 31, art 2 (entered into force 16 November 1994).

[47] Australia claims sovereignty over the territorial sea and seabed through Seas and Submerged Lands Act 1973 (Cth) s 6, which has been upheld by the High Court in New South Wales v Commonwealth (Seas and Submerged Lands Case) [1975] HCA 58; (1975) 135 CLR 337. As to the constitutional position with respect to the Australian States see Coastal Waters (State Title) Act 1980 (Cth); Coastal Waters (State Powers) Act 1980 (Cth); Port MacDonnell Professional Fishermen’s Assn Inc v South Australia [1989] HCA 49; (1989) 168 CLR 340; Butterworths, above n 1, [215-185].

[48] UNCLOS, opened for signature 10 December 1982, 1994 ATS 1994 31, arts 5, 6, 7 (entered into force 16 November 1994). Although, originally Australia had a 3 nautical miles territorial sea, in 1990 it was extended to reflect the position in UNCLOS. On 20 November 1990 the territorial sea was extended to 12 nautical miles by Proclamation under Seas and Submerged Lands Act 1973 (Cth) s 7. See also Brian Opeskin and Donald Rothwell, ‘Australia’s Territorial Sea: International and Federal Implications of its Extension to Twelve Miles’ (1991) 22 Ocean Development and International Law 395–431. The territorial sea remains at three nautical miles in the area around the islands in the Torres Strait, in accordance with the Treaty between Australia and the Independent State of Papua New Guinea concerning Sovereignty and Maritime Boundaries in the area between the two Countries, including the area known as Torres Strait, and Related Matters, opened for signature 18 December 1978, 1985 ATS 4, art 3(2) (entered into force 15 February 1985).

[49] Department of Defence, <http://www.defence.gov. au/media> at 23 March 2005.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Also ‘officers’ or ‘authorised persons’.

[52] Migration Act 1958 s 245F(1 8); Customs Act 1901 s 4 (although the Act does not specifically mention ADF members, but requires CEO authorisation to exercise powers under the Customs Act); Fisheries Management Act 1991 (Cth) s 83; Maritime Transport Security Act 2003 (Cth) s 147.

[53] In 1967 Australia established a 12 nautical miles fishing zone. From 1 November 1979, the AFZ was extended to 200 nautical miles. Butterworths, above n 1, [215-260].

[54] The EEZ was established as a new maritime zone to recognize coastal States’ claims for fishing zones. The rights and jurisdiction of Australia in its EEZ are vested in and exercisable by the Crown in right of the Seas and Submerged Lands Act 1973 (Cth) s 10A.

[55] The AFZ does not include coastal waters or areas of waters that are subject to an international agreement between Australia and a foreign country: Treaty between Australia and the Independent State of Papua New Guinea concerning Sovereignty and Maritime Boundaries in the area between the two Countries, including the area known as Torres Strait, and Related Matters, opened for signature 18 December 1978, 1985 ATS 4, art 7 (entered into force 15 February 1985); Torres Strait Fisheries Act 1984 (Cth).

[56] UNCLOS, opened for signature10 December 1982, 1994 ATS 31, art 11 (entered into force 16 November 1994).

[57] Article 111(1) mentions the territorial sea or contiguous zone of the coastal state. Article 111(2) stipulates that the right of hot pursuit applies mutatis mutandis to the EEZ and continental shelf.

[58] R v Lijo, Eiroa & Folgar [2004] WADC 29, which involved illegal fishing offences on a vessel within the Australia Fishing Zone whereby the vessel was apprehended outside the Australian Fishing Zone after hot pursuit.

[59] Subject to conditions under CaSA s 6.

[60] It would appear that the scheme was enacted due to the effects of Oteri and Another v The Queen (1976) ALR 142. In this case, the Privy Council went to extraordinary lengths to apply the English Ofences at Sea Act 1799 (UK) to alleged offences occurring 22 nautical miles from the Western Australian coastline.

[61] Including the Northern Territory but excluding the Australian Capital Territory.

[62] Attorney-General’s Department, Offshore constitutional settlement: A milestone in co-operative federalism (1980), 12.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Offshore constitutional settlement, above n 62, 7.

[65] This timeframe was to allow the States and Northern Territory time to enact their legislation under the scheme.

[66] CaSA, sch 2(2): The Crimes at Sea Act 1979 although repealed from 31 March 2001 when CaSA sch 1 commenced. However, the 1979 Act continues to apply in relation to conduct that took place prior to 31 March 2001. CaSA sch 2(3) also provides that where any conflict as to whether the conduct occurred either before or after commencement of sch 1, the presumption is that it occurred before commencement.

[67] The Australian Capital Territory was not involved in the cooperative scheme as it is land locked and has no traditional off-shore jurisdiction.

[68] Which is defined at CaSA sch 1 cl 1(1).

[69] CaSA, Preamble and sch 1 cl 1 Definitions.

[70] (2003) 203 ALR 189.

[71] Ibid, [204].

[72] Butterworths, above n 1, [270-2220 – 270-2260] discusses the structure of the CaSA but provides no discussion about the extent or application to the DFDA.

[73] Including the Northern Territory.

[74] CaSA sch 1, cl 1(1).

[75] CaSA sch 1, cl 1(1). This area extents the traditional State jurisdiction from 3 nautical miles.

[76] or the outer limit of the Continental Shelf, which ever is greater.

[77] CaSA sch 1, cl 1(1).

[78] CaSA s 4 and sch 1 cl 1(1).

[79] CaSA sch 1, appendix 1 – Indicative map.

[80] See above n 5 for list of the State and Northern Territory Crimes at Sea Acts enacted.

[81] CaSA sch 1, s 1. Law of criminal investigation, procedure and evidence means law (including unwritten law) about:

(b) immunity from prosecution and undertakings about the use of evidence; or

(c) the arrest and custody of offenders or suspected offenders; or

(d) bail; or

(e) the laying of charges; or

(f) the capacity to plead to a charge, or to stand trial on a charge; or

(g) the classification of offences as indictable or summary offences (and sub-classification within those classes); or

(h) procedures for dealing with a charge of a summary offence; or

(i) procedures for dealing with a charge of an indictable offence (including preliminary examination of the charge); or

(j) procedures for sentencing offenders and the punishment of offenders; or

(k) the hearing and determination of appeals in criminal proceedings; or

(l) the rules of evidence; or

(m) other subjects declared by regulation to be within the ambit of the law of criminal investigation, procedure and evidence; or

(n) the interpretation of laws of the kinds mentioned above.

[82] CaSA sch 1, s 1. Substantive criminal law means law (including unwritten law):

(b) dealing with capacity to incur criminal liability; or

(c) providing a defence or for reduction of the degree of criminal liability; or

(d) providing for the confiscation of property used in, or derived from, the commission of an offence; or

(e) providing for the payment of compensation for injury, loss or damage resulting from the commission of an offence, or the restitution of property obtained through the commission of an offence; or

(f) dealing with other subjects declared by regulation to be within the ambit of the substantive criminal law of a State; or

(g) providing for the interpretation of laws of the kinds mentioned above.

[83] The meaning of ‘unwritten law’ is not defined in the CaSA. It may refer to common legal procedural practices although the definition is left open for interpretation, possibly deliberately, or may refer to Customary International law with regard to the Laws of the Sea.

[84] See above n 3.

[85] CaSA sch 1, cl 2(1)–(2).

[86] CaSA sch 1, cl 3(1).

[87] CaSA sch 1, cl 2 (3)(a). An example provided by the CaSA with respect to incapability is: A law making it an offence to drive a motor vehicle at a speed exceeding a prescribed limit on a road could not apply in an adjacent area because of the inherent localising elements of the offence.

[88] CaSA sch 1, cl 2 (3)(b). An example provided by the CaSA regarding the lack of legal effect is: If the effect of a provision of the substantive criminal law of a State is limited under s 109 of the Constitution within the area of the State, the effect is similarly limited in the outer adjacent area for the State even though the provision applies in the outer adjacent area under the legislative authority of the Commonwealth.

[89] ‘Commonwealth judicial proceeding’ and ‘State judicial proceedings’ defined in CaSA sch 1, cl 3(1).

[90] CaSA sch 1, cl 3(2).

[91] Explanatory Memorandum, Crimes at Sea Bill 1999 (Cth) [43].

[92] See ‘Mission Complete’, above n 24.

[93] Balance of probabilities.

[94] An evidentiary burden is a lower standard when compared to the standard of balance of probabilities: Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) s 13.3 regarding ‘evidential burden’ and ss13.4, 13.5 regarding ‘legal burden’.

[95] CaSA sch 1, cl 7(1).

[96] CaSA sch 1, cl 7(2).

[97] CaSA sch 1, cl 7(3).

[98] CaSA sch 1, cl 7(4).

[99] Part 3A deals with the Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPD Area) which was developed through agreement between Australia and East Timor. The JPD Area applies Northern Territory criminal law.

[100] Putting aside the JPD Area at this time.

[101] CaSA s 6(11).

[102] CaSA s 6(1)(a).

[103] CaSA s 6(1)(b).

[104] CaSA s 6(1)(c).

[105] CaSA s 6(2)(a).

[106] CaSA s 6(2)(b).

[107] CaSA s 6(2)(c).

[108] CaSA s 6(3)(a).

[109] CaSA s 6(3)(b).

[110] CaSA s 6(3)(c).

[111] Australian Constitution s 5 1(xxix).

[112] CaSA, s 4 and sch 1 cl 1(1). ‘(a) a ship registered in Australia; or (b) a ship that operates, or is controlled, from a base in Australia and is not registered under the law of another country; or (c) a ship that belongs to an arm of the Defence Force.’ (Emphasis added).

[114] Ibid.

[120] CaSA s 6(10)(a).

[121] The laws of the Northern Territory apply.

[122] Ibid.

[123] CaSA s 6(10)(b).

[124] Within the Territorial Sea of Norfolk Island, the law of Norfolk Island applies.

[126] CaSA s 6A(2).

[127] As defined by CaSA s 6A(1).