University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

PETER SAUNDERS[*]

The passage through the Senate of the WorkChoices legislation represents a pivotal moment in the life of the Howard Government and a point of departure for an Australian social policy tradition that extends back to the early years of the last century. Although some in the government have described the reforms as not particularly radical and others have argued that further reform will be necessary, many analysts outside of the neo-liberal mainstream are fearful of their consequences for the institutional structures that have been the hallmark of Australia’s pragmatic but effective and coordinated approach to economic and social policy.

Much has been written about the economic case for why the reforms were necessary and what they will achieve. The basic argument is that in order to maintain our competitive position in an increasingly open global trading system, we must improve our own internal competitiveness, and the best way to achieve that is to place increasing reliance on market mechanisms that reward enterprise (and, although this is rarely mentioned, punish those who do not have the goods, skills or attributes demanded in the marketplace). Increased reliance on competitive forces, it is argued, will also promote increased productivity growth and rising living standards. Australia has been moving down this path for at least two decades following the deregulation of the financial markets by the Hawke-Keating Governments, although the pace of change has quickened under the economic reform agenda of the Howard Government.

Increasingly, as this process has unfolded, the regulations that existed in the labour market have been exposed as increasingly anomalous from a neo-liberal perspective that sees little place for institutions such as the trade union movement and a highly centralised industrial relations system built around the Australian Industrial Relations Commission (‘AIRC’). Both the trade unions and the AIRC have emphasised the rights of working people and the need to achieve – and protect – equity in wage outcomes, yet neither fit with the imperatives of supply and demand that increasingly drive outcomes in today’s labour market. These contradictions have been acknowledged in the slow drift towards enterprise bargaining and the demise of centralised wage determination, yet these shifts have to date been located within a regulatory framework policed by the AIRC, in which centralised wage bargaining and the award system remain important, along with the maintenance of a needs-based minimum wage floor through a quasi-judicial transparent safety net review process that operates independently of government.

But these mechanisms will be swept away under the new reforms, the former submerged by the spread of enterprise bargaining agreements, the latter to be replaced by a Fair Pay Commission that will give far greater control to the federal government, and (through its economist members) give emphasis to ‘the needs of the economy’ over ‘the needs of working people’. This shift has been described by two of Australia’s leading labour economists, Keith Hancock and Sue Richardson in the following terms:

The scenario that now looks the most probable is that workers in a range of industries, where unions retain a capacity to negotiate with the aid of credible threats of industrial action, will fare well; that some, whose skills are scarce, will prosper through employer competition to secure and retain their services; and that many others will have a hard time or depend increasingly on the protections of social security. Those protections, however generous, cannot replace the tribunals’ historic role of enforcing a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work.[1]

Such arguments rarely surfaced during the highly controlled debate that preceded the reforms, and when they did those who presented them were characterised as out of touch with modern realities, or as seeking to protect existing labour market privileges to the detriment of the majority. Yet implicit in these views is the idea that, even if the reforms succeed on their own terms, they will involve growing inequality in economic rewards and fewer protections for those unable to compete economically. The labour market will change, but so will the broader economic and social framework within which it is embedded.

In reviewing some of the arguments that are critical of the WorkChoices reforms, it is important to begin by noting that what is at stake is a major departure from Australia’s current economic and social trajectory. It is common for neo-liberal reforms to be justified on the grounds that they will generate economic benefits because this is what the economic theory on which they are based predicts will happen. However, this is self-serving, since what is at issue is the relevance of that theory to contemporary circumstances. Of course, if one accepts that the real world functions as the economics textbook assumes that it does, then it follows automatically that ‘textbook improvements’ will produce real benefits. But this puts the textbook cart very much before the real world horse: what matters is how well the theory captures the reality and where it fits awkwardly (or not at all), what the consequences of the proposed changes will be when account is taken of the role (and historical impact) of institutions like the union movement and the AIRC. In a world where people’s current circumstances depend upon how existing institutional structures have influenced historical trends, changes to these structures must form a central element of the analysis, yet neo-liberal economics is incapable of doing this because its own intellectual strictures see economic actors as unaffected by institutions and unshaped by history.

In order to gain a better understanding of the likely impact of the reforms, it is thus necessary to examine the impact of prevailing (pre-reform) policy. This involves assessing both the direct and indirect impacts of structures like the wage arbitration and welfare systems, the former focused on outcomes in the labour market and the latter on the flow-on effects in other areas. This approach is sketched out in Section II, which describes the role of the wage fixing system in the development of Australian social policy. Section III then discusses the short-term and longer-term effects of the IR reforms from a social policy perspective. Section IV concludes by arguing that we need to better understand the reforms and monitor their impact.

One of the most influential and enduring analyses of the Australian welfare state, developed by political scientist Frank Castles,[2] assigned a central role to wage and labour market regulation for achieving what other countries achieved primarily through social security legislation. When Justice Higgins’ ‘Harvester Judgment’[3] implemented the idea of a living wage in 1907, under which wages were set to meet the needs of a worker and his family, the wage system was assigned a pivotal role in achieving social protection through the wage safety net. This, according to Castles, explains the relative lack of generosity of Australian social security benefits, since the primary income support role was left to the wages system, operating through wage arbitration. This was the first of three central planks in an integrated approach to economic and social policy, the others being tariff protection of domestic industries and restrictions on labour supply through control of immigration.

The ‘Australian Settlement’ formed around these three principles was remarkably successful throughout much of the last century,[4] allowing Australia to perform well economically whilst avoiding the high levels of inequality found in the United States and the high social security budgets common in Europe.[5] Prior to the oil shocks of the 1970s, high levels of employment ensured that most Australians had access to an adequate wage, while very few working-age people needed to rely on the social security support because jobs were plentiful and unemployment scarce and sporadic. The fact that the original poverty line (developed in Melbourne in the 1 960s and endorsed by the Poverty Commission in the 1 970s) was set equal to the basic wage (with add-ons for those with children) ensured that the term ‘working poor’ was a contradiction in terms under conditions of full employment. At this time, there is an element of truth in the proposition that the social security (or welfare) system succeeded primarily because very few people needed it, and those that did quickly moved back into work.

The approach was, however, crucially dependent on the ability to maintain high levels of employment, alongside international competitiveness – the latter by controlling the flow of goods (through tariffs) and labour (through immigration). However, the system became susceptible as unemployment skyrocketed after the 1970s oil shocks and the climate of opinion among the policy elite shifted towards a more deregulatory economic environment. As this movement unfolded, the tariff protection pillar of the system became increasingly untenable, while the role of the wages system in protecting the living standards of Australian workers was gradually eroded. The latter was complicated by a series of other shifts including the increasing economic independence of women that challenged the ‘male breadwinner’ view of the world by radically altering the gender balance of the labour force, as well as by changes in the structure of industry and employment that saw a decline in the relative importance of full-time work and a growth in part-time and casual jobs.[6] These changes saw a decline in the dominance of the male, full-time, blue collar workforce, creating new challenges for the trade union movement and for the role of centralised wage bargaining.

The important point to note about this characterisation of the wage earner’s welfare state approach is that the counterpart to the comprehensive and adequate system of wage protection was a frugal and relatively ungenerous system of welfare benefits – at least by international standards. The fact that Australia had rejected the European approach to social security built around the Beveridge principal of social insurance in favour of a means-tested approach funded from general (tax) revenue also meant that the low levels of social benefits led to a low tax take (although the heavy reliance on income taxation made the taxes highly visible and led eventually to the pressure to introduce the GST). But the control of market forces through regulatory intervention in the labour market resulted in reduced pressure on the welfare system and a lower level of government spending. The form of state intervention was thus altered, though its scale or significance was not.

Over the longer-term, wages provided a floor below which social benefits could not fall, thus indirectly providing a broad safety net that protected workers and unemployed alike. However, heavy reliance on means-testing created ‘poverty traps’ that were thought (there were no studies that convincingly demonstrated the effects predicted by economic theory) to prevent those dependent on welfare from rejoining the labour force. Increasingly, the room to address these problems was constrained by the ever-growing complexity of a tax-benefit system that was a product of successive moves to better target the welfare dollar. A concern about growing ‘welfare dependency’ emerged as a major theme of the Howard Government’s social policy agenda in the late 1990s, when it established a Reference Group on Welfare Reform to advise on how to combat the growing numbers reliant on the welfare system.[7] One element of the McClure Committee’s welfare reform blueprint that found favour in the government focused on the strengthening of mutual obligation requirements through an expansion of Work for the Dole and similar schemes that increased the emphasis on job search activity by the unemployed, in the process making it harder for people to rely passively on welfare support.

More radical reform foundered on the inability of the Departments of Family and Community Services (‘FaCS’) and Employment and Workplace Relations (‘DEWR’) to agree on a package of reforms that inevitably spanned the interests of both. This bureaucratic obstacle was overcome by a departmental restructure that effectively transferred responsibility for the working-age (welfare) system from FaCS to DEWR following the 2004 election. This re-structure also allowed the IR reform agenda to progress in a form where its consequences for the welfare system (at least when viewed through a neo-liberal DEWR lens) could be more actively reviewed and embodied in the reforms as they were developed.

Before discussing these implications in detail, it is useful to review some of the achievements of the model that served Australia well in the past. Reference has already been made to the low levels of social security expenditure and wage inequality, and the international evidence bears this out. According to data compiled by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), for example, social security spending in Australia in 1997 (the pattern is similar in later years) was equal to 8.5 per cent of GDP, well below the OECD average of 12.8 per cent, and was lower in only three out of 23 countries (Korea, Japan and the United States).[8] There is also evidence from both the OECD and international research that the degree of wage inequality in Australia has been below that in many other countries, falling around the middle of the overall ranking throughout the 1980s and 1990s.[9] However, the evidence also indicates that wage inequality has been increasing in Australia in recent decades (as it has in many other countries), and that the level of wages at the bottom of the distribution has not kept pace with inflation, leading to a decline since the mid-1980s in the purchasing power of low (full-time) earnings among males and older workers generally.[10]

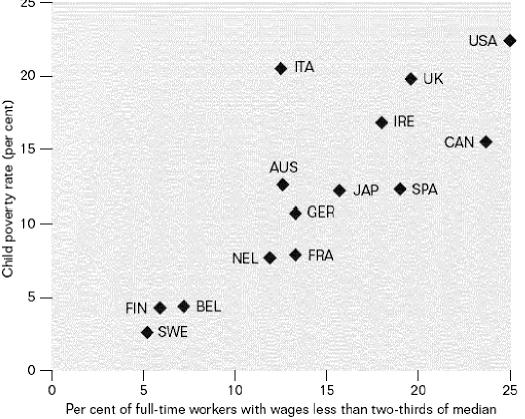

Australia also falls around the middle of the OECD range in relation to the incidence of low pay (defined as the percentage of full-time workers earning less than two-thirds of median full-time earnings) (see Figure 1),[11] although the incidence of low wages has also increased since the mid-1980s.[12] Furthermore, as shown in Figure 1, which is derived from a UNICEF study of child poverty, there is a close cross-country relationship between the incidence of low pay and the rate of child poverty.[13] There is no automatic assumption that the relationship shown in Figure 1 reflects a causal mechanism leading from low wages to increased child poverty. Indeed, Bradbury notes that it may reflect the opposite: where wages are low, benefits must also be low in order to maintain incentives, leading to high poverty rates,[14] or both low wages and child poverty may be indicative of an intolerant social attitude to inequality generally (of which both are indicative). However, the important point is that whatever the explanation, the evidence shows that counties with large sections of their labour force earning low wages also tend to have higher rates of child poverty – a combination that should raise concerns in any country that is actively seeking to increase the incidence of low wages.

FIGURE 1: INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON OF CHILD POVERTY AND LOW WAGES

Source: UNICEF (2000)

The comparison shown in Figure 1 suggests that wage levels reflect not only economic conditions in the labour market, but also how countries arrange their social policies. This illustrates more generally how state and market become inexorably interconnected under welfare capitalism, the key relationship in the current context reflecting the interaction between wages and the setting of social benefit levels. While wages and social benefits both independently reflect wider societal concerns over equity and the balance between economic and social objectives, the explicit links between them are also indicative of the wider policy stance. The wage earner’s welfare state is one example of this, but that is about to be replaced under WorkChoices, and the key question surrounds the impact of the new reforms. Although it is not possible to give a definitive answer to this question, the kinds of evidence reviewed above (which reflects past policies) can help to set broad parameters around the likely consequences of policy shifts, as the following discussion illustrates.

The discussion so far has drawn on a range of arguments and data to show how wage determination in Australia under the AIRC and its institutional predecessors was an integral part of a broader attempt to ensure that economic and social policy worked in unison to provide a wage safety net that, in combination with high levels of employment, offered Australian workers and their families an adequate level of social protection. Under this approach, the maintenance of an adequate minimum wage was central, along with the rejection of market forces in favour of social considerations when setting the minimum wage. It also implied that the minimum wage could not be viewed in isolation from the level of welfare benefits, since the minimum wage sets a limit to how far benefits can rise, with the gap between them influencing the incentive to work. The adjustment of many welfare benefits to price changes also ensured that wages would, at a minimum, keep pace with price rises in order to maintain the gap. The key point, however, is that the system generated and maintained a link between the wage floor and the level of social benefits, implying that changes to one could not be insulated from changes to the other.

Yet it is this link that the neo-liberal advocates of the WorkChoices legislation have attempted to break, arguing that minimum wage levels are excessive and detrimental to employment. This, it is argued, worsens the income prospects of those with few labour market skills who would be employed if wages were allowed to fall. The logic of the new reforms is thus to remove the constraints imposed by the previous industrial relations system and ‘free up’ the labour market so that wages can fall and create new employment opportunities. As Briggs, Buchanan and Watson have recently put it:

[T]he underlying logic of … the industrial relations changes … is accentuating labour market fragmentation and the polarisation of earnings in Australia. It is about the creation of a low wage sector in Australia comparable to that in the United States. For some economists, this is seen as the only solution to unemployment; for others, it meshes with their pre-conceptions of what defines an ‘efficient’ labour market.[15]

Other supporters of the reforms are less dogmatic about their ideological underpinnings, though equally convinced of their necessity. Noted labour economist Bob Gregory has recently reflected on his unease with the policy implications he has drawn from several decades of research into the labour market and welfare systems, arguing that:

All the policy interventions we have tried – across the board real wage freezes, large expansions of the education and training sectors, changes in immigration policy to focus on skilled immigrants, labour marker deregulation and the weakening of the trade unions – may have had positive effects but if so they are not enough to generate good employment outcomes for the unskilled and disadvantaged … The answer from Economics I is clear. To return to full employment all relative wages across skill categories need to change … the labour market needs to be deregulated and the wages of the disadvantaged should fall by a considerable margin to create jobs for them.[16]

The reliance on basic textbook economics is again revealing, a position that Briggs, Buchanan and Watson reject as being totally out of touch with the realities of a labour market that has undergone profound changes over the last two decades, moving it away from, not towards the neo-liberal textbook ideal.[17] However, with the reforms coming into effect, attention must now focus on what the outcome will be, and it is here that the earlier discussion becomes relevant. Although there has been little acknowledgement of this in political debate, one consequence of the reforms will be a decline in the level of low wages. The process of downward adjustment will take time (with the Fair Pay Commission likely to defer any major changes until well after the next federal election), but it is an inevitable consequence of the logic of the reforms, which are, after all designed specifically to achieve this result. This gives rise to two questions: first, will the decline in the minimum wage lead to an increase in employment at the bottom end of the labour market? Second, what other changes will the wage decline trigger? In relation to the first question, economists have not been able to agree on the size of the employment effect of a fall in wages, which depends on how responsive the demand for labour is to a fall in its price. The smaller this responsiveness (or elasticity) is, the more wages have to fall in order to generate a given increase in employment. While the reform proponents generally believe that the effects will be large, others take the view that falling wages by themselves will do little to improve the employment prospects of those who are currently unemployed or not in the labour force.

This argument is based on the view that many of those who have not been able to compete in the existing labour market face a range of problems – many of them deep-seated and inter-connected – that prevent them from getting a job. They include low levels of skill, declining morale and poor self-esteem, mental health and disability issues that limit their ability to participate, caring responsibilities (for children or adult family members), lack of transport and other infrastructure supports and discrimination on the part of employers. As Briggs, Buchanan and Watson note, ‘while many welfare recipients want to work, most employers don’t want to hire them’.[18] When faced with this formidable list of employment barriers, it is no surprise that some will find the reliability of a steady welfare income attractive and retreat into a life of jobless passivity that can lead to social exclusion and entrenched poverty. While there is a need to overcome this kind of self-fulfilling welfare dependent culture, the issue is whether wages cuts alone are capable of generating a turnaround, without in the process making life unacceptably harsh for those least able to respond. At the very least, the cuts in wages must be accompanied by policies that address the other barriers faced by the jobless. However, this will add to public spending and seems very low on the government’s list of priorities when it comes to dispersing the huge budget surplus it has accumulated – ranking well behind providing another round of tax cuts to the already prosperous (and far more numerous) group of middle class voters.

But even if these kinds of changes were introduced to support the switch from welfare to work (another key government priority), the logic of the argument set out earlier implies that the decline in wages will be accompanied by a decline in welfare benefits, otherwise the gap between wages and welfare will close, removing the incentive to shift from welfare to work. Again, the impact will depend upon how far wages need to fall, but here many labour economists agree that the extent of the decline will need to be substantial. As Gregory argued over a decade ago:

If labour market deregulation were to lead to a significant fall in earnings for the low paid it would also be likely to lead to a reduction in welfare payments to avoid the emergence of welfare traps. Consequently, a fall in wages at the bottom of the wage distribution is of concern to a wider range of people than those currently employed and the change in income distribution following upon a large fall in low wages would be considerable.[19]

So the decline in wages triggered by the WorkChoices legislation will give rise to pressures that unless resisted, will lead to a decline in the incomes of all welfare recipients, including those who have no realistic prospect of finding work either permanently (eg those with a severe disability) or temporarily (eg those lacking basic skills or looking after very young children). At the same time, those who are currently employed at low wages will find they become increasingly uncompetitive as wages around them start to fall, and this will eventually also lead to a decline in their wages; and as the wage falls spread through the labour market, the pressure to cut welfare benefits to maintain incentives will increase. So we will be in a situation where wages and welfare payments follow each other in a downwards spiral that will have devastating effects on the living standards of large numbers of Australians and their families.

While it might be possible to compensate those with children through changes to family tax-benefit arrangements (as has happened in the past), there are limits to how far this can offset the changes described above, and in any case, this will do nothing for the large numbers of workers who do not have children. The fiscal consequences of such offsets are also likely to make them an unattractive option for a government committed to tax cuts and a smaller role for government. While this turmoil is unfolding at the bottom of the labour market, those at the top who have the skills and power to benefit from the reforms will continue to do well, opening up even larger gaps between the haves and the have-nots.

We need only look to the United States to see how huge inequalities in economic outcomes – many of them a direct and intended consequence of policies designed to create greater incentives – can lead to a raft of entrenched social problems that, in the limit, pose a threat to social stability. It is notable that all of the research that has examined the international profile of poverty and inequality shows that the United States ranks at or near the bottom among OECD countries in terms of overall poverty, child poverty, working poor and inequality in the income distribution (see Figure 1 above).[20] This is not a situation that sits comfortably with the Australian ethos of ‘A Fair Go’, nor with the idea of providing people with an expanded range of choices built on a platform of social rights and legislated protections.

The traditional Australian industrial relations system was the cornerstone of an approach to economic and social policy that combined material prosperity with social justice and protection of the disadvantaged. Its structures will be swept aside by the market forces unleashed by the WorkChoices legislation, with effects that are uncertain and largely unknown. There is broad agreement that more has to be done to spread the benefits of economic growth to those who are unemployed and jobless, and that this requires a combination of policies that increase the attractiveness of paid work relative to the receipt of welfare. However, the new legislation puts the onus on the role of changing wages in generating new jobs, with far too little consideration of the implications for the labour market and the welfare system more generally.

The arguments developed here suggest that these flow-on effects will be considerable and have the potential to lead to a decline in the living standards of the many families currently dependent on either a low wage or an even lower welfare benefit. It seems inevitable that the phrase ‘working poor’ – historically a contradiction in terms under the institutions and policies of the wage earner’s welfare state – will become a reality for increasing numbers of working Australians and their families. We are heading down a road that will combine these pressures at the bottom with ever-widening gaps at the top, as those with the skills to compete in a more competitive labour market pull further away from everyone else. Social justice as traditionally conceived will disappear as market forces replace social policy as the criteria for distributing the fruits of economic progress.

In putting our faith in a competitive US-style labour market, we are dismantling an industrial relations system that has served the nation well for over a century (and was capable of being reformed in the light of changing economic and social conditions, albeit in the face of stern resistance from the trade union movement). Yet even the economic impact of the WorkChoices reforms is uncertain, while the social implications have largely been ignored in the run-up to its implementation. Yet these aspects pose a more fundamental departure from the past, giving rise to potentially more damaging consequences. At the very least, we need to monitor the impacts of the reforms on employment, living standards and inequality, so that we have a basis for better determining future policy.

[*] Professor Peter Saunders is the Director of the Social Policy Research Centre at the University of New South Wales.

[1] Keith Hancock and Sue Richardson, ‘Economic and Social Effects’ in Joe Isaac and Stuart Macintyre (eds) The New Province for Law and Order: 100 Years of Australian Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration (2004) 205.

[2] See generally Francis Castles, The Working Class and Welfare: Reflections on the Political Development of the Welfare State in Australia and New Zealand, 1890-1980 (1st ed, 1985); Francis Castles, ‘The Wage Earners’ Welfare State Revisited: Refurbishing the Established Model of Australian Social Protection, 1893-93’ (1994) 29 Australian Journal of Social Issues 120.

[3] Ex parte HV McKay [1907] CthArbRp 12; (1907) 2 CAR 1.

[4] Paul Kelly, The End of Certainty: The Story of the 1980s (1st ed, 1992).

[5] See Peter Saunders, The Ends and Means of Welfare: Coping with Economic and Social Change in Australia (1st ed, 2002); Paul Smyth and Bettina Cass (eds), Contesting the Australian Way, States, Markets and Civil Society (1st ed, 1992).

[6] Jeff Borland, Bob Gregory and Peter Sheehan (eds), Work Rich, Work Poor: Inequality and Economic Change in Australia (2001) 1-21.

[7] Commonwealth, Reference Group on Welfare Reform, Participation Support for a More Equitable Society: Full Report (2000) Department of Family and Community Services.

[8] Table 2.3 in Saunders, above n 5, 29.

[9] Table 3.2 in OECD (2004), Employment Outlook, OECD, Paris.

[10] Tables 5 and 7 in Peter Saunders, ‘Reviewing Recent Trends in Wage Income Inequality in Australia’ in Joe Isaac and Russell Lansbury (eds), Labour Market Deregulation. Rewriting the Rules (1st ed, 2005) 66.

[11] Sue Richardson, ‘Are Low wage Jobs for Life?’ in Joe Isaac and Russell Lansbury (eds), Labour Market Deregulation. Rewriting the Rules (1st ed, 2005) 149.

[12] Tony Eardley, ‘Working but Poor? Low Pay and Poverty in Australia’ (2000) 11 Economic and Labour Relations Review 308; Sue Richardson and Ann Harding, ‘Poor Workers the Link between Low Wages, Low Family Income and the Tax and Transfer Systems’ in Sue Richardson (ed) Reshaping the Labour Market: Regulation Eficiency and Equality in Australia (1st ed, 1998) 122.

[13] United Nations Children’s Fund, A League Table of Child Poverty in Rich Countries (2000) Innocenti Report Card No. 1, Innocenti Research Centre, Florence.

[14] Bruce Bradbury, Child Poverty: A Review, Policy Research Paper No 20 (2003) Department of Family and Community Services.

[15] Chris Briggs, John Buchanan and Ian Watson, ‘Wages Policy in an Era of Deepening Wage Inequality’ (Policy Paper No. 4, The Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia, 2006) 30.

[16] Robert George Gregory, ‘Australian Labour Markets, Economic Policy and My Late Life Crisis’ in Joe Isaac and Russell Lansbury (eds), Labour Market Deregulation. Rewriting the Rules (1st ed, 2005) 204, 218.

[17] Briggs et al, above n 15.

[18] Briggs et al, above n 15, 37.

[19] Robert George Gregory, ‘Would Reducing Wages of the Low Paid Restore Full Employment to Australia?’ in Peter Saunders and Sheila Shaver (eds), Theory and Practice in Australian Social Policy: Rethinking the Fundamentals, Reports and Proceedings No 111 (1993), Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales, 104.

[20] Anthony Barnes Atkinson, ‘The Luxembourg Income Study (LIS): Past, Present and Future’ (2004) 2 Socio-Economic Review 165. See also Michael Förster and Marco Mira d’Ercole, ‘Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries in the Second Half of the 1990s’ (Working Paper No 22, OECD, 2005).

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJl/2006/6.html