University of Technology, Sydney Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of Technology, Sydney Law Review |

|

This paper starts from the assumption that it is valuable to have a tool or tools that enable us to do effective worldwide legal research, in light of the enormous range of legal resources that are available for free access on the internet from every country in the world. The internet offers the unprecedented prospect of global access to legal information, so it seems the waste of a valuable resource not to be able to use it effectively. Academic research, in so far as it involves comparative research, will benefit from such a capacity. There are more direct and practical reasons for the need to develop tools to access legal research on the internet. Legal researchers in developing countries (including government draftspeople and law reformers, practising lawyers and NGOs) generally do not have any effective access to international comparative law materials. They increasingly need this access in order to reform their laws, or assess their compliance with international obligations such as WTO accession.

Since 1997 AustLII has been involved with the Asian Development Bank in Project DIAL (Development of the Internet for Asian Law)[1], a project which involves us attempting to develop effective means of accessing law on the internet worldwide (the “World Law” facility on AustLII), and in training legal officials in developing countries in Asia to use the Internet for legal research.

On Error Resume Next

On Error Resume Next

Part of the World Law homepage —

<http://dialworldlaw.org>

Living in a Web of

Giants

The largest internet directories (also called catalogs, or indexes) —and Ask Jeeves — have between one and two million links to websites, categorise the sites into at least 200,000 categories, and employ between 100 and 200 editors (or “indexers”). The Open Directory claims to have 36,000 volunteer indexers.[2].

Other tools used to find information, such as search engines based on webspiders (also called robots), are even larger. Danny Sullivan summarises the history of search engine growth:[3]

[quote]When AltaVista appeared in December 1995, it used an index much larger than any of the other search engines at that time. Thus, competition forced most of them to increase their sizes in early 1996. Notice that from September 1996 until September 1997, none of the search engines increased size significantly, despite the fact that the web continued to grow. From September 1997 through the end of 1998, AltaVista and Inktomi competed for the bragging rights of being the biggest. But by 1999, the fight to be biggest revolved between AltaVista, Northern Light and FAST Search. In January 2000, FAST announced it had broken the 300 million page mark, giving it the largest index of the web. Soon after, AltaVista did the same. By June 2000, Google broke the 500 million page mark, while WebTop.com also weighed in at that level. In addition, some Inktomi partners began using that company’s new 500 million page index in July 2000. By June 2000, Google hit a new record for search engines -- 1 billion documents indexed.[end q]

By mid-2001, Sullivan[4] assessed the number of webpages indexed by the web spiders of the largest search engines as highest for Google (1 billion[5] — 1000 million), followed by FAST (625 million), AltaVista (550 million), Inktomi (500 million), Excite (380 million) and Northern Light (350 million). Another estimate by Notess is much the same, except it estimates Google lower at 750 million pages[6] and adds another contender, Wisenut (510 million). Google’s own site claims to search 1600 million webpages.

Many catalogs and search engines are now hybrids — alliances between the provider of a catalog and the provider of a search engine.[7] For example, Google uses the Open Directory for its catalog, and Yahoo! uses Google for its search engine. Whatever their value for research on other subjects, they do not do everything that is needed for effective legal research using the internet: law-specific facilities like World Law are still needed.

The major catalogs on the web provide surprisingly little coverage of law. Looksmart has only one page on non-US law, with a handful of links.[8] The Open Directory Project, whose catalog is also used by Google and Ask Jeeves, has over 17,000 entries under its main law page,[9] but almost 10,000 of them are US law firm sites, and 2000 of the rest relate to law enforcement organisations, so the general law coverage is slight. There is also a very small amount of coverage in other languages.

Yahoo!’s coverage is harder to assess, as there is no central point of access for law worldwide. It has the most substantial law coverage of the general catalogs. Its largest law page is its US page, and lists about 3,000 sites, with a subject index of only 25 categories.[10] There are law sites indexed under most individual country pages, but most of them only have a handful of links. The limited attention given to law by the web’s major catalogs, at least on a global level, is reason enough to continue with the development of World Law as a law-specific catalog with global coverage.

The law component of a general internet catalog would usually be the wrong place to start internet legal research. Where they are useful, it would be valuable if those pages could be cross-referenced from a more comprehensive law-specific index.[11] However, in our 1999 paper[12] we explained some of the reasons why catalogs alone are inherently inadequate:

[quote]Catalogs are hard to maintain. As the quantity of legal material on the internet grows, the sites that contain significant legal information grow so numerous, and some are so large, that it is difficult to maintain catalogs at all, and particularly to maintain them with any depth of indexing of each site. The best that can be hoped for is that sites with significant legal materials are identified in the index, even though there is no detailed description of their content. For example, it soon becomes impossible to include in a catalog the content of each piece of legislation, each case, or each journal article included on a large site. As a result, we can say that catalogs are inherently shallow — even when they are good at identifying important law sites, they cannot index very deeply into those sites.[end q]

A law-specific catalog like World Law will never be sufficient for comprehensive internet legal research. The question that this raises for World Law, if we want it to be a comprehensive tool, is whether its catalog should be integrated with a law-specific search engine, with a general internet search engine like Google, or with both.

In 1999, a study by Lawrence and Giles estimated that the combined coverage of all of the search engines they tested was 42 per cent of the total number of webpages, a decline from 60 per cent in their 1997 study, and that there had been a decline in the coverage of the single best search engine from about 33 per cent to 16 per cent of the estimated total size of the web.[13] As a result they were pessimistic about the future of search engines:

[quote]Why do search engines index such a small fraction of the Web? There may be a point beyond which it is not economical for them to improve their coverage or timeliness. The engines may be limited by the scalability of their indexing and retrieval technology, or by network bandwidth. Larger indexes mean greater hardware and maintenance expenses, and more processing time for at least some queries on retrieval. Therefore, larger indexes cost more to create, and slow the response time on average.

[end q]

Other have argued that Lawrence and Giles may even have overestimated.[14]

The percentage of total webpages indexed by these search engines is still uncertain. Google certainly covers far more pages than search engines did before 1999, and its response times are very fast, but the web has also grown in size, and the extent to which the percentage of webpages covered is now greater than in 1999 is unknown.

In addition to the expanding size of the web, there are many technical reasons why search engines cannot make searchable many types of information found on the web, as detailed in our 1999 paper and by Dahn.[15] In our 1999 paper we also set out reasons why general search engines are biased in favour of “popular” pages, do not provide unbiased worldwide coverage, and are increasingly compromising the objectivity of their search results by selling priority places in their relevance ranking. All of these factors are still relevant.

In 1999 we drew the conclusion that “it would be unrealistic to expect general purpose internet-wide search engines to provide a very effective method of [carrying out] a task as specialised and ‘non-popular’ as internet legal research”. This conclusion is still largely true, if what is meant by “very effective” is “comprehensive”. However, the vast size of the web, the rapidly expanding size of Google (and the few competing search engines), and the costs of the computing resources needed to create a web spider search engine which covers even a tiny fraction of the entire web means that internet-wide search engines, for all their imperfections, are more indispensable than they ever were.

When we started World Law/DIAL in early 1997, the AltaVista search engine had only recently been launched, and it was realistic to think that a law-specific search engine might produce results comparable in scope with a general internet search engine. Now, five years later, no law-specific search engine can hope to have the resources to index more than a fraction of the significant legal information on the web — at best, the “most significant” legal web sites from around the world could be covered. This poses two questions:

We think that the answer to both these questions is still “yes” in the case of World Law, and will attempt to demonstrate why and how we have come to these conclusions.

World Law now includes over 4100 different categories (pages) into which legal websites are classified, and links to over 13,500 websites or parts of websites. In addition there are over 3500 cross-references, and over 1000 embedded searches.[16] Although there are many other law-specific indexes on the web,[17] none that are multinational are as large or globally comprehensive as World Law. As the largest multinational catalog of law sites on the internet, the work that has been put into the World Law catalog’s development is worth continuing as a free international resource.

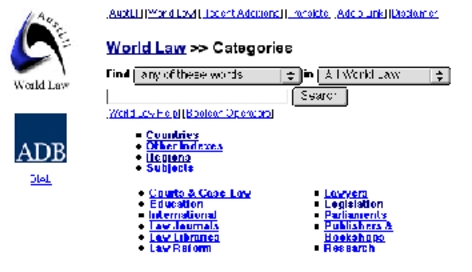

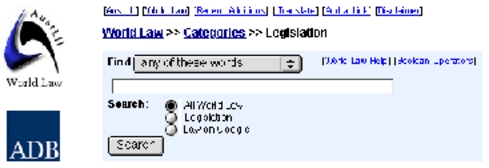

Start page of the World Law catalog — “Categories”

World Law’s catalog, as illustrated by the opening page above, indexes websites by more than one criterion. For example, the same site (or part of a site) will be indexed according to the country to which it relates (or under the relevant “International” subcategory), often by its source or type of subject matter (under “Legislation”, “Courts and Case Law” etc), and often by its subject matter (under almost 100 subject subcategories).

The financial resources to support the development of World Law are limited,[18] sufficient to support the equivalent of three full time staff (2.25 indexing/cataloguing staff, 0.75 technical support staff). Until now, content addition has principally been by AustLII staff.

The size of the World Law index means that World Law must now adopt a slightly different strategy for its future development. Expansion of DIAL’s content “contributors” strategy is planned, whereby experts in a particular country or subject matter become major contributors to that part of DIAL (with credit given, and links to their sites). Wherever possible, those involved in DIAL “portals” will contribute to relevant content, as they have a strong interest in its quality.

The pages on elections law show Elections Canada as a contributor

Project-oriented expansion of subject pages is another form of prioritisation, where a particular subject matter ties in with an ADB project, or another funded project elsewhere. An example is the expansion of the WTO and China-WTO pages, which will tie in with the development of HKLII, and is also a high priority of the Chinese users of World Law.

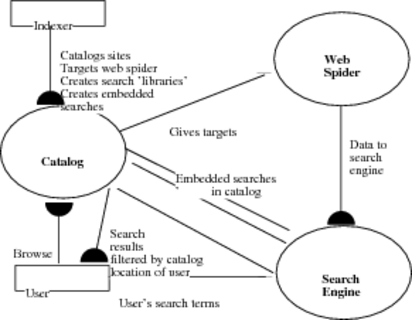

World Law’s approach to a law-specific search engine was explained in our 1999 paper (summarised in the diagram below) as the use of the catalog to ensure that the web spider only goes to sites relevant to legal research, and does not browse the web randomly. The catalog can then also be used to provide a method of filtering search results. We are not aware of any other multicountry examples of a law-specific search engine based on the use of a web spider[19], although domain-specific search engines do occur in other disciplines. Maintaining both a catalog and a web spider (and search engine) requires more resources than most legal catalogs have available.

Relationship between catalog, web spider and search engine in World Law

The default search for World Law searches automatically over two types of content: (i) the text of the pages of the catalog; and (ii) the text of all pages of all websites in the catalog that our web spider has been able to index. The way results are displayed is discussed below.

A search window appears on all World Law catalog pages, in the form shown in the example of the “Legislation” page below. The default search option is “Any of these words” (logical “or”), with the other user-selectable options being “All of these words” (logical “and”), “This phrase” and “This Boolean query”.

The Boolean search option allows the use of a full range of logical and proximity connectors, as shown below:

|

and

|

page contains both terms

|

negligen* and defam*

|

|

or

|

page contains either of two terms

|

weapon or gun or firearm or pistol

|

|

not

|

page contains 1st term but not the 2nd

|

trust not family

|

|

near

|

1st term is within 50 words of 2nd

|

disclos* near offence

|

|

w/n or /n/

|

1st term is within n words of 2nd

|

court w/5 jurisdiction

|

|

pre/n

|

1st term must precede 2nd term by less than n words

|

contempt pre/3 court

|

Table of search connectors used in World Law (SINO search engine)

The appendix to this paper provides further details.

Every catalog page now gives the user three choices of search scope. “All World Law” is now the default search option, as this gives the broadest search results, and is easiest for users to understand. It searches over all pages from websites in the catalog that World Law has been able to index.

Users who wish to do a narrower search must choose the second “radio button” option, which limits the scope of the search to those sites listed on or “below” the page from which the search is sent. In the example below where the search is from the “World Law >> Categories >> Legislation” page, if the second radio button is selected, the search will cover all legislation from any country (but only legislation). If the search was from the “World Law >> Categories >> Countries >> New Zealand” page it would search only over sites related to New Zealand law.

Previously, this narrower search scope was the default option, but our DIAL training experience has shown us that only the more sophisticated users understood that their search was narrow in default, and many users were therefore puzzled as to why their searches produced few results. Yahoo! and Open Directory now also offer limited scope searching (they had not done so when World Law implemented it in 1999), and have made the same choice of default search scope.

Search options as they appear on the “Legislation” category

This limited scope searching is only valuable when the page from which search is sent has numerous subcategories and/or websites listed on it. It is particularly useful on a page like the “Legislation” page above, as that page includes cross-reference links to every country category in the world where legislation is available on the web. We are not aware of any other location on the internet where one search can be made over legislation from many countries, but limited only to legislation sites.

World Law’s web spider has indexed less than 20 gigabytes of websites relating to law, comprising some millions of web pages — the exact number is uncertain. The scope of World Law searches will always be tiny compared with internet-wide search engines such as Google or AltaVista.

For comprehensive legal research it is obviously necessary to use such an internet-wide search engine. Google claims to cover 1,610,476,000 web pages (at 1 November 2001), and as noted earlier it does appear to index the largest number of pages on the web at present by a considerable margin. Tests by Notess also show Google producing more results to a range of queries than other search engines,[20] and this coincides with our own subjective observations on the value of Google searches.

The third new option in the search interface on every catalog page allows the user to search “Law on Google”, as illustrated in the example of the “Legislation” page above. We have chosen to integrate World Law searches more closely with one search engine, rather than giving users a choice of search engines to “Repeat this search over...” by simply sending their search terms to another search engine. The main reason for this approach is that different search engines use different syntax for their searches, so a search over World Law, if using Google and AltaVista, could come up with three quite different sets of results. Google has been selected because it gives the best results at the moment. We may decide from time to time to send World Law searches to a different search engine.

In order to make World Law searches as effective as possible over Google, we have implemented automatic translation of DIAL searches to Google searches, with two features:

Google’s search syntax requires all words used in search terms to be found, unless an “OR” operator is used. This is effectively the same as Google having a default “and” (or “all of these words”) operator. For the most accurate translation of World Law searches to Google searches it is necessary for World Law searches to be transformed by the following substitutions:

|

World Law syntax

|

Google substitution

|

Comment

|

|

“Any of these words”

|

no change

|

See comment below

|

|

“All of these words”

|

no change

|

Google default is the same as a logical “and”

|

|

“This phrase”

|

places phrase in double quotes

|

|

|

“or” in Boolean query

|

replaces with “OR”

|

Google requires capitalisation of “or” to

“OR”

|

|

“and” in Boolean query

|

removes “and”

|

Google default

|

|

“near” in Boolean query

|

removes “and”

|

Google does not support proximity in queries, but automatically recognises

it in document ranking

|

|

“*” (truncation) in Boolean query

|

forward user to help page, advising removal of truncation

|

Google does not support truncation; automated substitution is not

possible

|

A World Law “any of these words” search looks at first sight as though it places a logical “or” between search terms, but in fact because the relevance ranking algorithm used by SINO first displays results which include all of the search terms used, and only then displays results which include only some or one of the search terms, the result is closer to an “all of these words” search in most cases. The closest result from Google is achieved by leaving the search terms untouched (an implied “and” between the words), rather than by placing Google’s “AND” operator between the words.

Only a tiny percentage of the pages searchable by Google are law-related. This causes a problem when translating searches from a law-specific search engine where the legal context of searches is assumed, because only law-related materials can be retrieved. Searches for legal materials use many search terms with meanings in other contexts, so often the problem with a general search engine like Google is how to find the law-related materials without them being swamped by the non-law materials and effectively unfindable because they are buried in a retrieved list of thousands of items. For example, the search “fishing fiji” will only find legal materials when used as a search over World Law, but if used as a search over Google the first few pages of results are exclusively about fishing holidays in Fiji.

In order to deal with this problem of legal context, the automated translation of a World Law search has appended to it the following additional search terms: “(law OR legal OR legislation OR regulation OR judgment OR treaty)”. This addition of six “law-specific” words, only one of which needs to be present in a document for it to be retrieved, seems generally to produce an improved result.

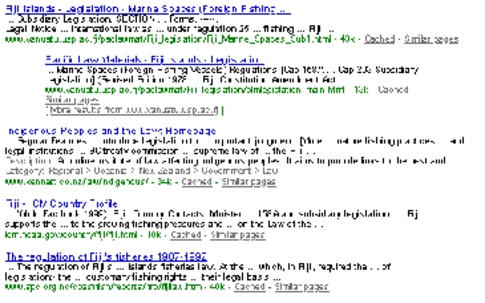

For example, the search “fishing fiji”, when automatically translated into “fishing fiji (law OR legal OR legislation OR regulation OR judgment OR treaty)” produces Google results where the first few pages are almost entirely concerning with the law regulating fishing and fisheries in Fiji, as illustrated by the first few results below.

First few results of the translation of a “fishing fiji” search over Google

The law-specific terms that we use may be able to be refined with experience, but it seems that the addition of legal contextual terms will often be necessary. Care is needed, because the addition of seemingly obvious terms like “court” can have adverse effects because of its use in the context “tennis court”. Where a user provides numerous search terms, Google will remove the automated terms to the extent that the total terms exceeds ten.

Despite the far greater breadth of Google searches, they do not make World Law’s law-specific searches redundant. One reason for this is that Google’s relevance ranking method (which is based to a large extent on giving a higher ranking depending on how many other sites link to a page) is very different from the more conventional relevance ranking method used by World Law (based on frequency of occurrence of search terms, moderated by their overall frequency of occurrence, and their location in the documents found). As a result, Google and World Law can present very different documents at or near the head of a ranked list. “Unpopular” pages, even if very relevant, can be made more difficult to find if pushed well down into a very long list of Google search results.

For example, the most important case on Hong Kong’s basic law deals with issue of the “right of abode” of Chinese-born people in Hong Kong. A World Law search for “right of abode near Hong Kong” gives as its first-ranked result the text of the key decision of the Court of Final Appeal of Hong Kong. However, a Google search for these terms or any form of them (with or without the law-specific terms added) produces many relevant press articles and government sites referring to the decision, but the text of the decision itself is pushed many pages down into the search results. One reason for this may be the greater popularity of newspaper and government department pages as compared with the webpages of the Court of Final Appeal.

While examples like this are hardly conclusive, our interim conclusion is that a law-specific search engine such as World Law (and there are no other examples we know of) remains as a useful complement to a general search engine such as Google. For comprehensive internet legal research, it is desirable to use both.

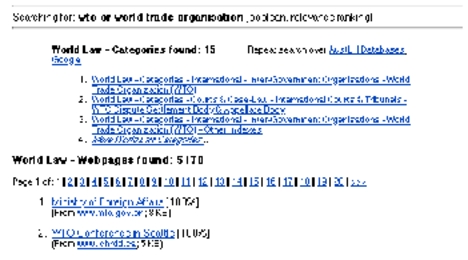

World Law search results are now presented in a similar way to what is now becoming the “industry standard” for results presentation (based on a survey of major search engines). The three most relevant Categories (i.e. World Law catalog pages) to a search request are listed at head of the search results (with an option to view “More World Law Categories...”), with the webpages on sites covered by the World Law search facility then listed.

Display of World Law search results showing display of main catalog pages first

On every page of search results, the user is also invited to repeat their World Law search over Google, with their search translated into Google search syntax as described above.

The search results also give the user an additional option of repeating the search over AustLII. This option is to be replaced shortly by the option of repeating the search over WorldLII (World Legal Information Institute), which will provide combined search results over case law, legislation and secondary from AustLII (Australia and New Zealand), BAILII (UK and Ireland), PacLII (fourteen Pacific Island countries), HKLII (Hong Kong), and databases on WorldLII from South Africa and other jurisdictions.

This approach will integrate World Law and WorldLII from the World Law end. When implemented, it will give users three classes of searches that they can implement automatically from World Law: (i) consistently presented high quality legal databases on WorldLII; (ii) other less consistently presented legal data accessible via World Law’s law-specific search engine; and (iii) the largest general search engine, Google.

The complement to the above approach is to make relevant World Law category pages available to users at the time they are searching or browsing major national free access law sites. These are the sites that attract most users of free access legal materials, who may be more likely to find World Law via those sites than by accessing it directly from the AustLII site.

This strategy is in the process of being implemented with the following Legal Information Institutes (LIIs): AustLII, BAILII, PacLII, and the soon to be launched HKLII. The strategy is now being extended as we seek the participation of other major free access law sites as “World Law hosts”. The first to be implemented will be at the WITS Law School, the major provider of free access to South African legal materials.

This “portal strategy” has three elements:

An example of the implementation is seen on the following search results from the Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute (PacLII), where the three World Law categories most relevant to the user’s search precede the results from the PacLII databases, and the user is also given the option of repeating the search over World Law websites. The World Law categories appear in the same standard way at the top of the PacLII search as they do in a World Law search.

A search over PacLII showing display of World Law categories

As mentioned at the outset, one of the practical drivers behind the development of World Law is Project DIAL (Development of the Internet for Asian Law), funded by the Asian Development Bank. DIAL involves AustLII in providing training in internet legal research for government legal officials (particularly legislative draftspeople and law reformers) in seven Developing Member Countries (DMCs) of the Bank in Asia. To date, initial training sessions have been carried out in Mongolia, China, Vietnam, the Philippines and Indonesia, with training yet to commence in Pakistan and Cambodia.

DIAL training at the National Law Development Agency, Jakarta

The aim of the training programme in each country is that AustLII (and our regional training coordinators from CD-Asia in the Philippines) find and work with local training partners to develop a training programme that the training partner can adapt to local circumstances and sustain. For this reason, our training partners have tended to be government legal research institutes and university law schools that have a long term interest in providing internet legal training.

The World Law facilities are presented only in English at present. There are medium term plans to make the facility more multilingual, but the inevitably limited budget of a free access facility, and the global (or at least pan-Asian) range of users that World Law/DIAL is intended to assist, means that the “built-in” multilingual capacity will always be limited. The “[Translate]” option at the top of every DIAL page now provides a facility to translate automatically from English to Chinese (and to Korean and Japanese), as well as to five other European languages. The translation facility is provided by AltaVista. We hope that AltaVista will add other languages used in DIAL DMCs such as Indonesian and Vietnamese.

Chinese translation of the top half of the “Categories” page in World Law

The World Law home page gives users a specific message that they can translate into Chinese (see the home page illustration at the start of this paper). Once the translation is started, all DIAL pages then appear in Chinese. This was a very popular facility in our Beijing training and was used by most of the trainees in preference to the English version for at least some of the time.

Many of the Beijing users made use of the “View Original Language” facility provided by AltaVista, shown above, which opens a separate browser window with the English language version of the catalog page. Since the translations are automatic, they are not always reliable, but our users’ experience is that they have generally been good enough to be helpful with pages containing short descriptive items, such as the catalog pages. Where the translation was not helpful, users found it very useful to have the English and Chinese versions side by side, and would browse across the web in this bilingual fashion, obtaining assistance from both versions.

[*] Graham Greenleaf is Co-Director, AustLII, and Professor of Law, University of New South Wales (currently Distinguished Visiting Professor, University of Hong Kong, Faculty of Law); Philip Chung is Executive Director, AustLII, and Lecturer in Law, University of Technology, Sydney; Russell Allen is Project Officer, AustLII, responsible for the technical maintenance of World Law; Madeleine Davis is Project Officer, AustLII, and indexer for World Law; Takao Hasuike is Project Officer, AustLII, and indexer for World Law.

[1] About DIAL on AustLII (visited 17 November 2001).

[2] Directory sizes” page <http://searchenginewatch.com/reports/directories.html> on Danny Sullivan, Search Engine Watch website <http://searchenginewatch.com/> (visited 17 November 2001).

[3] Danny Sullivan Search Engine Sizes” from The Search Engine Report, 15 August 2001, on Search Engine Watch website <http://searchenginewatch.com/> (visited 17 November 2001).

[4] ibid

[5] By another measure, Google can draw on 1.25 billion sites to produce results, as it can direct users to some sites simply because other sites have linked to them, even if its web spider has not indexed those sites.

[6] Greg R. Notess, “Search Engine Statistics: Database Total Size Estimates” (data from: 14 August, 2001) on Search Engine Statistics Showdown (visited 17 November 2001).

[7] For examples, see Danny Sullivan Search Engine Alliances Chart http://searchenginewatch.com/reports/alliances.html, ibid.

[8] <http://www.looksmart.com/eus1/eus317836/eus552286/eus53716/eus1158453/r?l &> (visited 17 November 2001).

[9] <http://dmoz.org/Society/Law/> (visited 17 November 2001).

[10] <http://dir.Yahoo!.com/Government/Law/> (visited 17/11/2001)

[11] The “Other Indexes” page under each country entry in World Law does this for many of the Yahoo! pages.

[12] G Greenleaf, D Austin, P Chung, A Mowbray, J Matthews and M Davis, (2000) “Solving the Problems of Finding Law on the Web: World Law and DIAL”, The Journal of Information, Law and Technology (JILT) 1 <http://www.law.warwick.ac.uk/jilt/00-1/greenleaf.html> also in Proceedings, 16th Biennial LAWASIA Conference, Seoul, Korea, 7–11 September 1999 (referred to hereinafter as “1999 paper”).

[13] Steve Lawrence and C. Lee Giles (1999) “Accessibility of information on the Web” Nature, Vol. 400, 8 July 1999, 107–09 — not available in full on the web, but see “Accessibility and Distribution of Information on the Web” <http://www.wwwmetrics.com/> (visited 17 November 2001).

[14] Michael Dahn Counting Angels on a Pinhead: Critically Interpreting Web Size Estimates” ONLINE, January 2000 <http://www.onlineinc.com/onlinemag/OL2000/dahn1.html> (visited 19 November 2001).

[15] Ibid.

[16] More details of World Law’s content development are in Davis et al (2002), “Managing Secondary Legal Resources on AustLII”, presented at the UTS “Law and the Internet” conference.

[17] See the Other Indexes pages in World Law <http://www.austlii.edu.au/links/320.html> for an extensive list, including multinational, national, and subject-specific law indexes.

[18] At a rough approximation, AUD$175,000 per annum at present, of which approximately half is from the Asian Development Bank (and includes the costs of DIAL training in developing countries), and half is from the cataloging component of other AustLII funded projects, including funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC) under a “research infrastructure” grant.

[19] The only example previously know, Jurist’s search facility <http://jurist.law.pitt.edu/search.htm> , is now limited to pages on its own site.

[20] Greg R. Notess Search Engine Statistics: Relative Size Showdown: Google on Top’” <http://www.searchengineshowdown.com/stats/size.shtml> (visited 17 November 2001): “This size showdown compared nine search engines, with MSN Search and HotBot representing the largest of the Inktomi partners. This analysis used 25 small single word queries. Google found more total hits than any other search engine. In addition, it placed first on 19 of the 25 searches, more than any of the others."

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UTSLawRw/2002/2.html