eJournal of Tax Research

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

eJournal of Tax Research |

|

Abstract

This study evaluates the influence of education on tax compliance among undergraduate students in Malaysia. The survey considers existing literature in the field of education and ascertains whether education can influence the respondents’ compliance behaviour. The statistical findings confirm the prevalence of a relationship between education and tax compliance. This relationship is generally consistent, particularly so to the questions relating to general avoidance and personal avoidance. There is an improvement in personal tax compliance among students especially among females after one semester of pursuing a preliminary taxation course. It is suggested that universities providing courses in social science as well as business, management and accounting studies should offer the preliminary taxation course as a core subject to all their students.

Past research has indicated that tax evasion, especially in small amounts, is not viewed as being morally wrong or considered as a serious crime (Song and Yarbrough, 1978; Westat, 1980; Yankelovich, Skelly and White, 1984). Several research findings have reported a positive relationship between taxpayers’ view of tax evasion as wrong and tax compliance behaviour (Scott and Grasmick, 1981; Thurman, John and Riggs, 1984; Kaplan, Reckers and Roark, 1988; Klepper and Nagin, 1989; Grasmik and Bursik, 1990). Basic principles of taxation include low compliance costs; certainty in tax law and minimal interference with economic incentives to work, save and invest.

According to Andreoni, Erard and Feinstein (1998), there is a need for more empirical and institutional research on compliance behaviour within jurisdictions outside the United States (US). As for Malaysia, there has been little research dealing with taxpayer attitudes on tax compliance and the possible influence of education on those attitudes. This research contributes, albeit in a small manner, to a better understanding of Malaysian taxpayers’ attitude towards tax compliance. In the United States (US), Hite (1995) observed that the level of education was not linked to evasion or avoidance. In a research carried out in the US and Hong Kong, Chan, Troutman and O’Bryan (2000) found that US respondents’ decisions to comply with their tax laws were mainly driven by their age and education. Meanwhile, Hong Kong respondents have a lower level of moral development, a less favourable attitude towards the tax system, and consequently a lower level of tax compliance.

In New Zealand, Lin and Carrol (2000) examined the linkages between an increase in tax knowledge on perceptions of fairness and tax compliance attitudes by using students enrolled in an introductory taxation course in a tertiary institution. Their results indicated that an increase in tax knowledge did not have a significant impact on perceptions of fairness and tax compliance attitudes. This result is inconsistent with the findings of other researchers (see Crane and Nourzad, 1990) who found a positive linkage.

The literature section deliberates on the definition of tax avoidance and tax evasion followed by a review of the theoretical framework surrounding tax compliance.

Tax avoidance and tax evasion

Tax resistance takes two basic forms: evasion and avoidance. Evasion of tax is immoral as it is illegal (Brown, 1983). Tax evasion is meant to be deliberate acts of non-compliance resulting in payment of lower taxes than are actually owed. Therefore, not paying ‘ones’ lawful share of tax is evasion of income. On the other hand, tax avoidance, which denotes the taxpayers’ ingenuity to arrange his affairs in a proper manner so as to reduce the incidence of tax, is legal. As long as the provisions of the law are not violated and transactions bona fide, any attempt to minimize tax is acceptable.

The term non-compliance encompasses both intentional evasion and unintentional non-compliance which is likely due to calculation errors and inadequate understanding of tax laws. A particular taxpayer may intentionally evade some of his or her obligations while intentionally being non-compliant in other aspects. Intentional non-compliance to reduce or eliminate the amount of tax payable requires some measure of understanding of the tax system. While there may not be a one to one correlation, it may be reasonable to assume that the greater the understanding of the tax system, the greater is one’s ability to ‘hookwink’ the system. If so, there is a direct relationship between understanding the tax system and the probable propensity to evade the full payment of tax.

Evasion can take place in a number of ways. Individuals may choose to underreport their true income. They may also overstate adjustments in moving from Total Income to Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), or claim excessive deductions from AGI when computing taxable income. Kolm (1973) stated that some degree of tax evasion was expected and tolerated. The author (Kolm) estimated that one-third of the French income tax base fails to be reported to the revenue authorities.

Taxation is a social phenomenon that comprises of political, social and legal aspects and can be influenced by attitudes. Thus, in order to change taxpayer behaviour, it requires great care and effort (Van Hoorn, 1978). Crane and Nourzad (1990) found that individuals with higher levels of income tend to evade more. Citizens with greater tax education may be aware of non-compliance opportunities such as tax loopholes and hence there is a reduced likelihood of deliberate non-compliance (tax evasion). The findings of a study by Peacock and Shaw (1982) revealed that an increase in tax evasion will result in an expansion of domestic income and a contraction in the Government’s tax revenue if the marginal propensity to spend out of tax evaded is less than unity. Clotfelter (1983) evidenced that successful tax evasion has serious consequences to Governments as it not only cause losses in current revenues but it fosters a threat to voluntary compliance.

Theoretical framework on tax compliance

Achieving tax compliance is costly for both tax authorities and taxpayers. Tax audit and investigation is obviously costly to tax authorities (Allingham and Sandmo, 1972). Compliance is also costly to taxpayers, who must keep records as well as consult tax professionals and this is particularly true under a self-assessment system. Malaysia introduced a self-assessment tax system in stages commencing with companies from year of assessment 2001. In 2004, it would apply to all categories of taxpayers, including individuals. Slemrod and Sorum (1984) suggested that the compliance cost of managing individual income taxes in developed countries is between five and seven percent of revenue raised. According to Henry (1983), perfect compliance to tax law is not a rational objective for public policy.

Most taxation systems in the world reveal that taxation authorities employ a mixture of enforcement activities and penalties in order to enforce tax compliance. Research in the US (Schwartz and Orleans, 1967) and in Sweden (Vogel, 1974) found that taxpayer norms are important in analysing individual behaviour towards tax obligations. Spicer and Lundstedt (1976) found that the internalised norms and role expectations in each taxpayer are the major role elements in taxpayer choice between tax compliance and tax evasion.

Taxpayers are less compliant when they perceive the tax system to be unfair (Spicer and Becker, 1980 and Mustafa, 1997). Jackson and Milliron (1986) listed out variables that relates to compliance such as tax evasion behaviour, gender, occupation and risk attitude. In their study, they found that attitudes are more important than opportunities in determining taxpayer behaviour. Older taxpayers are found to be less willing to take risks and are more sensitive to sanctions. Meanwhile, females tend to be more conforming, conservative and bound by moral restraints. Single taxpayers are less compliant apparently because they are less risk averse (Tittle, 1980).

In the US, available statistics suggest that there was an increase in the level of tolerance for tax evasion from 35 percent in 1966 to 44 percent in 1979. Silver (1995) carried out a survey on university students and he found that 56 percent of the students disagreed that most people are honest in paying their taxes.

Relationship between tax compliance and education

Roth, Scholz and Witten (1989) identified two primary factors that have a significant effect on taxpayer compliance: financial self-interest and moral commitment. Financial self-interest assumes that individuals maximize their expected utility by reporting on income that balances the benefits of successful evasion against the consequences of detection. Thus, the importance of detection and sanctions are the primary means to increase compliance.

Chan, Troutman and O’Bryan (2000) carried out a survey to compare compliance behaviour between Hong Kong and US taxpayers. They found that the US respondents’ decisions to comply with tax laws were primarily driven by their age and education, which in turn positively influenced moral development and attitude. In contrast, Hong Kong respondents have shown a negative link between education, moral development, attitude and compliance. Although Hong Kong subjects felt the tax system was generally fair, lower levels of education and moral development moderated such a positive perception, which both contributed indirectly to a less favourable attitude.

This research examined several norms of accounting students at University Utara Malaysia (UUM) to determine what impact these norms may have on the participants’ responses to several tax question scenarios such as honesty and sense of moral duty towards the taxation system.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the influence of education on tax compliance among undergraduate students at UUM. This study considers existing literature in the field of education and ascertains whether education can influence the respondents’ compliance behaviour. Consequently, the study explores whether education has an effect on accounting undergraduates’ attitude towards tax evasion and tax avoidance. This study extends prior compliance research by finding support for a link between individuals’ education and compliance intentions. The findings of the study would be useful to create awareness of voluntary tax compliance through education under the self-assessment system.

A questionnaire was administered on UUM accounting students to determine whether education influences respondents’ tax avoidance and tax evasion behaviour.

Survey Procedure

The questionnaires were distributed to University Utara Malaysia accounting students who had yet to commence their taxation course. The study therefore, would exclude students who had taken the taxation paper at the diploma level.

Pilot Study

Initially, the questionnaire was pre-tested by enrolling lecturers attached to the School of Accountancy, UUM as respondents. The criticisms of the five commentators on this study were helpful in preparing the final questionnaire. The findings of the pilot study were not reported as it was merely meant to improve the structure of the questionnaire. After improving the survey instrument so as to eliminate ambiguous questions , the questionnaire was distributed to the respondents.

Data Collection Method

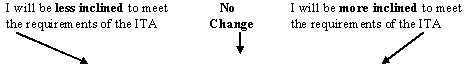

The instrument used for this quasi-experimental research was a survey questionnaire. The tax-case based scenario questionnaires were sent to a total of 560 students who commenced their preliminary taxation paper for the May 2001/2002 semester. The tax-case scenario questions relied on respondent’s basic knowledge of the Income Tax Act (ITA) to determine the outcome of the survey findings. From the total of the questionnaires that was distributed, 553 were completed, providing a response rate of 98.75% for the beginning of the semester. Seven of the questionnaires were rejected due to insufficient data. At the end of the semester, the same set of questionnaires, with one additional question was distributed to the set of sample. The additional question posed the following scenario to the respondents:

“My study of tax this semester has influenced my attitude to my own income tax affairs in the following manner”

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

Out of 560 questionnaires that were distributed at the end of the semester, 551 were returned by the respondents providing a response rate of 98.39%. Five of the questionnaires were rejected due to insufficient data, leaving a total of 546 usable responses.

The Questionnaire

The questionnaire was divided into two parts: Part A and Part B. Part A consisted of four tax case scenarios to measure the behavioural dimension of respondents to tax compliance. After reading each scenario, the respondents were asked to evaluate (on a seven-point “Likert” scale) whether he or she would report their earned income if faced with an identical situation. Part A of the questionnaire comprised of four questions. The first question is structured to gain response to a general public evasion (GE) issue. The second question seeks response to a general public avoidance (GA) issue. The third question relates to a personal evasion (PE) matter and the last question deals with personal avoidance (PA). As mentioned earlier, at the end of the semester, one additional question was added to the same set of questionnaire. The additional question sought from respondents whether their attitude on tax affairs had changed after studying the taxation subject for one semester.

Part B (“demographic information”) solicits respondents’ background information such as gender, age, ethnic group and work background of parents.

Data Analysis

In Part A, a Likert scale was used for most of the questionnaires and the respondents had to tick the appropriate column. In Part B, the questionnaires required a tick for the correct answer. The responses derived from the questionnaires were coded, entered and analysed by using the SPSS statistical package.

This section reports on the respondent’s characteristics, and results of hypotheses introduced for this study.

Respondent’s Characteristics

A summary of the characteristics of respondents is reported in Table 1. For both sets of questionnaire, the percentages of sample characteristics are broadly the same. The sample characteristics suggest that about 26% of the respondents were males and 74% were females. Seventy-one percent of the respondents were Malays, 23% were Chinese, four percent were Indians and two percent were others.

Most of the respondents (84%) are between 20 and 30 years of age. This is because the respondents are undergraduate students pursuing a degree program at University Utara Malaysia (UUM). About one-quarter of the student’s parents (24%) are employed with the Government but most of them (48%) are employed with the private sector.

Hypotheses Testing

The research hypotheses were structured to seek answers to the issues raised in the introduction section, that is, the association, if any, between (i) extent of tax compliance and (ii) level of education. As mentioned earlier, the respondents completed the questionnaires at the commencement as well as at the end of the semester. The survey questionnaires for each of groups were coded in relation to the respondent’s background data and the mean scores for each survey question were then determined.

|

|

Percent |

|

Gender

Male

Female

|

25.7

74.3

|

|

|

100.0

|

|

Ethnic Group

Malay

Chinese

Indian

Others

|

70.7

23.5

4.0

1.9

|

|

|

100.0

|

|

Age

Below 20 years

20 to 30 years

Over 30 years

|

15.4

84.4

0.2

|

|

|

100.0

|

|

Parent’s work background

Sole proprietor/partnership

Government servant

Employed in private sector

Others

|

15.6

23.7

47.7

13.0

|

|

|

100.0

|

|

Parent’s approximate annual income (Year: 2000)

Below RM18,000

RM18,001 to RM36,000

Above RM36,001

|

87.4

9.9

2.7

|

|

|

100.0

|

* Number of respondents: 546

The first hypothesis was posited in relation to respondents’ scores over time (period of tax education).

H-1: There is no difference in the mean scores of students at the commencement

of the semester and at the end of the semester.

Data to test hypothesis, H-1, was gathered from students who completed the Taxation 1 program in May 2001. The student’s responses to four taxation scenarios were obtained at the commencement of the semester, and student responses to the same questions were gathered at the end of the semester. No student was identified in relation to his or her response in order to make it confidential and to encourage truthful responses. As such, individual responses could not be compared. Only total responses were analysed. Table 2 summarizes the student mean scores to each of the questions on both occasions.

|

|

Commencement of the semestern = 553

|

End of the semestern = 551

|

||

|

|

Means |

Standard Deviation |

Means |

Standard Deviation |

|

Q1 GE

|

4.02

|

1.45

|

3.99

|

1.44

|

|

Q2 GA*

|

4.78

|

1.34

|

5.30

|

1.32

|

|

Q3 PE*

|

4.22

|

1.31

|

4.41

|

1.41

|

|

Q4 PA

|

3.39

|

1.34

|

3.41

|

1.39

|

* Significant at 5% level

Note: GE: General Evasion GA: General Avoidance PE : Personal Evasion PA : Personal Avoidance

Hypothesis H-1 was partially accepted because the t-test revealed that there was significant difference at five percent level for GA (t=6.51, df=1102, p<0.05) and PE (t=2.41, df=1102, p<0.05). The students seem to be neutral as to whether it is acceptable under the Income Tax Act (ITA) to under-report the income if faced with special circumstances such as unfair tax laws or economic hardship, at the beginning of the semester. After undergoing the tax course, the results showed that student attitudes to the given tax scenarios had changed over time. These findings suggest that students may have become more compliant on tax avoidance and evasion through participation in tax education.

In order to understand whether education can influence students’ tax compliance attitude, further tests were carried out in terms of gender and ethnic background. The following hypothesis was formulated, that is:

H-2: There is no difference between the mean scores of males and females

in relation to attitude change after one semester of tax education.

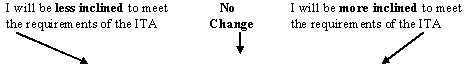

Although hypothesis H-1 indirectly tested the influence of one semester of Taxation 1 education on tax compliance attitude of students, hypothesis H-2, was posited as a direct test of students’ own view on a possible change in attitude. At the end of the semester (November 2001), the students were asked an additional question which reads as follows:

“My study of tax this semester has influenced my attitude to my own income tax affairs in the following manner.”

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

Student responses were then expressed on a seven point Likert scale with a score of 1 showing a negative change in attitude and a score of 7 displaying a positive change in attitude to the requirements of Income Tax Act (hereafter referred to as the Act) 1967. Table 3 displays the mean responses to this new question posed at the end of the semester.

|

|

End of Semester

|

|

|

Question Number

|

Males n = 130

|

Females n = 421

|

|

Q5 (Personal Perception)

Mean Response Score

|

5.07

|

5.35

|

Hypothesis H-2 was accepted as the mean scores of males and females were 5.07 and 5.35 respectively in relation to question 5 (Personal Perception). T-test statistics revealed that the difference was significant at 5% level (t=2.40, df=549, p<0.05). Our study revealed that both male and female mean scores fell in the upper half of the Likert scale, suggesting that in the minds of the students, there was some degree of improvement in tax compliance, highly likely due to tax education. This finding substantiates earlier survey reports carried out in the US and Hong Kong [Hite (1995) and Chan, Troutman and O’Bryan (2000) which showed similar results.

Table 4 focuses on the mean scores of females on the four taxation scenarios at the beginning and at the end of the semester. The results revealed that there is significant difference among female attitudes in respect of general avoidance (GA) tax issues at the commencement and at the end of the semester (t =5.94, df =830, p<0.05) and PE (t =2.44, df =830, p<0.05). The results suggest that education can remarkably influence the attitude of female students. Consequently, the results indicate that female students are more aware about the legal implications of tax evasion and tax avoidance, compared to male counterparts, after having completed one semester of tax education.

|

|

Mean

|

Standard Deviation

|

||

|

Question Number

|

Commencement of Semester

|

End of Semester

|

Commencement of Semester

|

End of Semester

|

|

Q1 GE

|

4.02

|

3.99

|

1.42

|

1.40

|

|

Q2 GA*

|

4.72

|

5.25

|

1.28

|

1.30

|

|

Q3 PE*

|

4.22

|

4.44

|

1.25

|

1.38

|

|

Q4 PA

|

3.36

|

3.37

|

1.25

|

1.37

|

* Significant at 5% level

Note: GE: General Evasion GA: General Avoidance PE: Personal Evasion PA: Personal Avoidance

Similar analysis were also undertaken on male attitudes as shown in Table 5. The t-test results revealed that there is a significant difference among male attitudes between the commencement and the end of the semester for only GA (t=2.91, df=270, p<0.05). The findings suggest that male students have shown an improvement in the understanding of the legal provisions pertaining to general tax avoidance under the Act. Indirectly, it has proved that male students’ attitudes in respect of general tax avoidance under the Act have changed after undergoing the tax course for one semester.

|

|

Mean

|

Standard Deviation

|

||

|

Question Number

|

Commencement of Semester

|

End of Semester

|

Commencement of Semester

|

End of Semester

|

|

Q1 GE

|

4.01

|

3.97

|

1.53

|

1.55

|

|

Q2 GA*

|

4.94

|

5.45

|

1.49

|

1.39

|

|

Q3 PE

|

4.21

|

4.32

|

1.46

|

1.52

|

|

Q4 PA

|

3.48

|

3.55

|

1.57

|

1.48

|

* Significant at 5% level

Note: GE: General Evasion GA: General Avoidance PE: Personal Evasion PA: Personal Avoidance

The third hypothesis on participant’s gender was proposed as follows:

H-3: There is no difference in the mean scores of attitudes between males

and females on each survey.

|

|

Commencement of Semester

|

End of Semester

|

||||

|

Question Number

|

Male

|

Females

|

t test

|

Male

|

Females

|

t test

|

|

Q1 GE

|

4.01

|

4.02

|

-0.04

|

3.97

|

3.99

|

-0.16

|

|

Q2 GA

|

4.94

|

4.72

|

1.70

|

5.45

|

5.25

|

1.51

|

|

Q3 PE

|

4.21

|

4.22

|

-0.04

|

4.32

|

4.44

|

-0.82

|

|

Q4 PA

|

3.48

|

3.36

|

0.89

|

3.55

|

3.37

|

1.34

|

Note: GE: General Evasion GA: General Avoidance PE: Personal Evasion PA: Personal Avoidance

Hypothesis H-3 was accepted. It was observed that in both surveys carried out at the commencement and end of the semester, there was no significant difference in attitudes between male and female groups. The fourth hypothesis on participant’s ethnic group was proposed as follows:

H-4: There is no difference in the mean scores of attitudes among ethnics groups at the commencement of the semester and at the end of the semester.

Table 7 shows the mean scores for ethnic groups over time (tax education) Results of ANOVA revealed that there are significant differences among ethnic group attitudes for tax education in (General Evasion) GE (F7,1096=4.68, p<0.05) (General Avoidance) GA (F7,1096=7.83,p<0.05) and (Personal Evasion) PE (F7,1096=3.78, p<0.05).

|

|

Commencement of Semester

|

End of Semester

|

||||||

|

Question Number

|

Malay

|

Chinese

|

Indian

|

Others

|

Malay

|

Chinese

|

Indian

|

Others

|

|

Q1 GE

|

4.10

|

3.78

|

3.68

|

4.8

|

4.15

|

3.71

|

2.83

|

4.12

|

|

Q2 GA

|

4.81

|

4.58

|

5.09

|

5.4

|

5.26

|

3.35

|

5.09

|

6.0

|

|

Q3 PE

|

4.33

|

3.92

|

3.64

|

4.7

|

4.42

|

4.29

|

5.04

|

4.29

|

|

Q4 PA

|

3.41

|

3.38

|

3.00

|

3.8

|

3.34

|

3.61

|

3.02

|

3.65

|

The Least Square Distance (LSD) tests indicated that differences existed at the 5% significance level as follows:

Q1GE (General Evasion)

In this category, the change in attitude among the ethnic groups was examined. The mean scores of compliance (GE) attitude of Indian students have changed over time from 3.68 to 2.83 suggesting that tax education had the greatest impact on this ethnic group for GE compared to Malays and Chinese students.

Q2GA (General Avoidance)

The mean scores of attitudes (GA) for Malay and Chinese groups have changed from 4.81 to 5.26 and 4.58 to 3.35 respectively. Malay students have positively reacted to tax education for GA but the reverse is true for Chinese students.

Q3PE (Personal Evasion)

The mean scores of attitudes (PE) of Chinese and Indian groups have changed from 3.92 to 4.29 and 3.64 to 5.04 respectively. Again, tax education had the greatest impact on Indian students on PE compared to Chinese and Malay students.

The results of the study are generally consistent with the hypotheses posited in the paper. It is found that there is a relationship between education and tax compliance which is partially consistent with hypothesis 1, particularly so to questions relating to ‘general avoidance’ and ‘personal evasion’. With higher level of education, both male and female respondents changed their attitude in meeting the requirements of the Malaysian tax law. This finding is supported by hypothesis 2.

Furthermore, the findings indicate there is no difference in attitudes between male and females and this is in line with hypothesis 3. The statistical findings of this study confirm the existence of a relationship between education and tax compliance. Therefore, it is suggested that universities offering social science courses as well as business and management studies should offer the preliminary taxation course as a core subject to all their students. Currently, the taxation course is offered as a compulsory subject to all accounting-based undergraduates. It will be useful if the taxation paper is also offered to other students pursuing non-accounting courses. This is because when undergraduate students are subsequently employed and earn taxable income, they will more likely to be compliant with tax laws. If the employees had adequate tax knowledge, then there would be minimal unintentional non-compliance. When there is tax evasion among those who have adequate tax knowledge, then, it is as a result of deliberate non-compliance that would then attract higher tax penalties. Indirectly, this study does make a contribution towards a better understanding of internalised norms of Malaysian taxpayers.

The principal limitation to this study is due to the small sample size covering UUM accounting students. Consequently, it is not appropriate to make a generalization on the change in attitude among Malaysian taxpayers resulting from tax education, although there are indications to suggest that this view is likely to be true. Furthermore, it can be argued that the responses in this study may not accurately reflect the tax-paying public as a whole. The findings of this study show that education may significantly influence the tax compliance behaviour of students. More studies need to be carried out among accounting students from other public and private universities so that the results can be realistically compared to gather more accurate responses. A comparison could also be made among undergraduates from different countries to investigate how the results would differ.

Allingham, M. G. And Sandmo, A. (1972), Income Tax Evasion:A Theoritical Analysis, Journal of Public Economics, 1: 323-338.

Alm, J. (1991), A Perspective on The Experimental Analysis of Taxpayer Reporting, The Accounting Review, 66: 577-593.

Andreoni, J., Erard, B. and Feinstein, J. (1998), Tax Compliance, Journal of Economic Literature XXXVI:818-860, June.

Brown, C.V. (1983), Taxation and the Incentive to Work, Oxford University Press, pp 2-32.

Chan, C. W.,Troutman, C. S.and O’Bryan, D. (2000), An Expanded Model of Taxpayer Compliance:Empirical Evidence from the United States and Hong Kong, Journal of International Accounting Auditing and Taxation, 9(2): 83-103.

Clotfelter, C. T. (1983), Tax Evasion and Tax Rates:An Analysis of Individual Returns, Review of Economics and Statistics, 65: 363-373.

Crane, S. E. and Nourzad, F. (1990), Tax Rates and Tax Evasion:Evidence from California Amnesty Data, National Tax Journal, 43(2).

Grasmick, H. G. and Bursik, R. J. (1990), Conscience and Rational Choice: Extending The Deterrence Model, Law and Society Review, 24: 837-861.

Henry, J.S. (1983), Noncompliance with U.S. Tax Law-Evidence on Size, Growth and Composition, The Tax Lawyer, Vol 37: 1-91.

Hite, P. A. (1995), Identifying and Mitigating Taxpayer Compliance, Paper Given at Australian Tax Compliance Conference, Canberra, December.

Jackson, B. R. and Milliron, V. C. (1986), Tax Compliance Research: Findings, Problems and Prospect, Journal of Accounting Literature ,l 5 :125-165.

Kaplan, S. E., Reckers, P. M. J. and Roark, S. J. (1988), An Attribution Theory Analysis of Tax Evasion Related Judgments, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 13 :371-380.

Klepper, S. and Nagin, D. (1989), The Deterrent Effect of Perceived Certainty and Severity of Punishment Revisited, Criminology, 27 :721-746.

Kolm, S. (1973), A Note on Optimum Tax Evasion, Journal of Public Economics, l 2.

Lin, M.T. and Carrol, C.F. (2000), The Impact of Tax Knowledge on the Perceptions of Tax Fairness and Attitudes Towards Compliance, Asian Review of Accounting, 8(1): 44-58.

Mustafa, H. M. H. (1997), An Evaluation of the Malaysian Tax Administration System and Taxpayers’ Perceptions Towards Assessment Systems, Tax Law Fairness and Tax Law Complexity, PhD Thesis, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Sintok.

Peacock, A. and Shaw, G. K. (1982), Tax Evasion and Tax Revenue Loss, Public Finance, 37 :268-278.

Roth, J. A., Scholz, J. T. and Witten, A. D. (1989), Taxpayer Compliance, Volume 1:An Agenda for Research, Philadelphia:University of Pennsylvania Press.

Schwattz, R. and Orleans, S. (1967), On Legal Sanctions, University of Chicago Law Review, 34 :274-300.

Scott, W. J. and Grasmick, H. G. (1981), Deterrence and Income Tax Cheating:Testing Interaction Hypothesis in Utilitarian Theories, Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 17: 395-408.

Silver, D. P. (1995), Tax Compliance Attitude, National Public Accountant, 40(11): 32-34.

Slemrod, J. and Sorum, N. (1984), The Compliance Cost of The U. S. Individual Income Tax System, National Tax Journal, 37 :461-471.

Song, Y. and Yarbrough, T. (1978), Tax Ethics and Taxpayer Attitudes: A Survey, Public Administration Review: 442-452.

Spicer, M. and Becker, L. (1980), Fiscal Inequity and Tax Evasion:An Experimental Approach, National Tax Law Journal, 33 :171-175.

Spicer, M. N. and Lundstedt, S. B. (1976), Understanding Tax Evasion, Public Finance, 31: 295-305.

Thurman, Q.C., John, C. S. and Riggs, L. (1984), Neutralization and Tax Evasion:How Effective Would A Moral Appeal Be In Improving Compliance to Tax Law, Law and Policy, 6: 309-327.

Tittle, C. (1980), Sanctions and Social Deviance:The Question of Difference, New York: Praeger.

Van Hoorn, J. Jr. (1978), Problems, Possibilities and Limitations with Respect to Measures Against International Tax Avoidance and Evasion, Georgia Journal of Internatonal and Comparative Law, 8: 763-777.

Vogel, J. (1974), Taxation and Public Opinion in Sweden:An Interpretation of Recent Survey Data, National Tax Journal, 27: 499-513.

Westat, Inc. (1980), Individual Income Tax Compliance Factors Study, Rockville, MD:Westat, Inc.

Yankelovich, Skelly and White, Inc. (1984), Taxpayer Attitudes Study:Final Report, Prepared for The Internal Revenue Service, US.

[+] This paper is a revised version of the paper presented at the Hawaii International Conference on Business, Honolulu, 8-22 June 2002. The authors thank the grant committee at University Utara Malaysia for their financial support to conduct the survey.[]

[∗] Professor, Faculty of Accountancy, University Utara Malaysia

[†] Lecturer, Faculty of Accountancy, University Utara Malaysia

[‡] Lecturer, Faculty of Accountancy, University Utara Malaysia

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/eJlTaxR/2003/7.html