Federal Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Federal Law Review |

|

Kimberlee G Weatherall[†] and Paul H Jensen[∗]

Patents are growing in importance. Patenting rates worldwide have increased significantly in recent years: between 1992 and 2002, the number of patent applications in Europe, Japan and the US increased by more than 40 per cent.[1] Patent coverage has also been extended to include new kinds of inventions, like genetic technologies,[2] software,[3] and business methods.[4] A wider range of participants are also using patents, with universities being encouraged to increase their patenting activity.[5] And there has been a dramatic increase in patent litigation, at least in the US.[6] These facts have given rise to international debate on the costs and benefits of the patent system and how its effectiveness in encouraging innovation might be improved.[7]

To inform these debates, policymakers have called for more hard data on how the system is actually working in practice.[8]

Enforcement forms an important part of how the patent system 'works'. Patents are designed to encourage innovation by providing innovators with legal protection against expropriation of their innovative products and processes by third parties. The effectiveness of this legal protection depends not only on the existence of patent laws 'on the books' but also on the ability to enforce the rights granted in the courts. Historically, however, there has been a relative dearth of information on how the enforcement 'side' of the patent equation is working.

This historical lack of information is being addressed overseas, particularly in the US, by a burgeoning empirical literature.[9] However, to date, there has been only limited empirical work in Australia. The purpose of our study is to begin to plug that gap, by examining the use of the Australian court system as a mechanism for enforcing patent rights. We have conducted an empirical study of patent enforcement outcomes[10] in Australian courts during the period 1997–2003. In this paper, we provide some results of that study, giving a broad picture of what is happening in patent disputes before the courts. We intend that this study will provide a solid factual foundation for policy debates and serve as a basis for further research.

There is at present an ongoing debate in IP circles in Australia with regard to the performance of Australia's IP system. One common perception often voiced in this debate is that patent owners have received inadequate protection in Australian courts.[11] We argue that there are two fundamental problems with the debate as it currently stands. The first problem is that although it is essentially an empirical issue, there is little objective data on the outcomes of the patent litigation process — the debate has largely been based on anecdotal evidence provided by groups with a vested interest in the issue. Empirical research on litigation outcomes is relatively rare in legal research in Australia.[12] This paper makes an important contribution to the development of empirical research on patent litigation outcomes. Second, there is a poor understanding of what actually constitutes the optimal level of enforcement. Many existing studies are critical of the observed low levels of success for patent owners in patent litigation disputes without properly recognising that patent rights are probabilistic in nature — a patent does not provide any guarantee of validity if challenged in a court of law — and that this has implications for what an appropriate 'win rate' for patent owners might be.

To remedy these two problems, we present this paper in two parts. In the first part, we review the literature on litigation, with particular reference to patent litigation. We examine the rationale for the creation of patents, discuss some recent criticisms of the Australian courts with regard to patent protection and analyse in more detail why we need a framework for evaluating the optimal level of enforcement in the courts. Our aim is to highlight the extreme care with which any statistics in this area must be treated.[13] In the second part, we undertake a broad empirical study of patent litigation outcomes in Australia using a newly-created database which contains data on all judgments in civil IP enforcement actions in courts of superior jurisdiction over the period 1997–2003.[14] We set out the methodology used in the construction of the database and the analysis of the data and then we report the results of recent patent enforcement cases in Australia in terms of both validity and infringement. Finally, some conclusions are drawn and consideration is given to the use of this data set in other research projects.

Although the existence of IP rights — in particular, patents — has been questioned in the economics literature at various times, it is generally considered that, on balance, a system of providing limited monopoly rights to inventors is socially beneficial.[15] Moreover, while various economic rationales are used to justify the existence of patent rights, it is clear that whichever is chosen, enforcement is central to the whole system's effectiveness.[16]

According to one school of thought, patents are justified because they provide an 'incentive to invent'.[17] The basic argument is that patents correct the failure of unfettered markets to provide the socially optimal level of innovation. The reason that this failure occurs is that in order to innovate, firms must invest in research, development and commercialisation of products. However, once created, inventions are often easy and inexpensive to copy. In an unregulated market, anyone could 'free ride' on the inventor's investment and expropriate the invention, with the result that inventors will not be able to recoup their costs — leading firms to under-invest in innovation ex ante.[18] To prevent this outcome, most governments have intervened in the operation of the free market by creating a system of patents. Patents provide monopoly rights for a limited time, giving the creator a limited period of exclusivity in which to recoup their investment, but allowing competitors to enter the market thereafter.

In this framework, enforcement is crucial: patents can only be effective in preventing free-riding if it can be demonstrated in a court that a third party has infringed the patent. If third parties know that it is difficult to establish patent infringement in the courts, their disincentive to avoid infringing is reduced and the likelihood of infringement increases. The result may be to destroy ex ante investment in innovation.

A second economic rationale for the existence of patents is the contract or bargain theory of patents, which argues that patents offer inventors a limited monopoly right in exchange for public disclosure of the invention and how to make it.[19] Patents can thus increase the benefits of innovative activity, both by promoting the diffusion of knowledge and indirectly by promoting innovation: while people cannot make the patented invention, they can use the information in the patent application to invent around it.[20] This 'public disclosure' role of patents also depends on their enforceability. Real (or perceived) weaknesses in the enforceability of patent rights increase the likelihood that inventors, where they are able, will choose to rely on laws that protect trade secrets.[21] This in turn reduces the diffusion of knowledge, thereby decreasing the social benefits from innovation.[22]

Finally, patents also facilitate market exchange, which is becoming increasingly important, particularly as firms become more specialised and as the expense of new technology requires significant investment from numerous sources. They provide inventive firms with something to sell or license, enabling them to attract necessary investment or partners to take products through to commercialisation. Patents can do this by solving the Arrow paradox: the idea that inventors may need to disclose their invention to sell or license it to others but will hesitate to disclose for fear of copying.[23] By giving inventors legal recourse to protect their investment, patents allow disclosure without fear of expropriation by a potential partner, investor or customer.[24] While the effect of enforcement is less direct here, it is still important. Patents which are less enforceable are less valuable to partners or investors. Inventors who are less able to license or sell at the full value of the invention may fail to exploit their invention to the fullest extent.

In summary, the goals of the patent system — innovation and investment on the one hand and knowledge dissemination on the other — cannot be achieved unless parties can effectively and efficiently enforce their patent rights. Furthermore, the perception about how effectively the enforcement system is operating is arguably as important as the reality. For inventors and investors at the margins, if the system is seen to be ineffective, they may avoid using the patent system altogether. In this context, the effectiveness of the system for patent enforcement in Australia is an important policy issue and it is therefore essential to obtain a better understanding of how the system is working, in the interests of both the policy-makers who can improve it and the patent owners who use it.

So patent enforcement matters, and perceptions about patent enforcement also matter. This means that there is all the more reason to study patent enforcement outcomes in Australia in light of the negative publicity it has received in the recent past. For example, some IP practitioners have registered concern that 'the courts give too little protection to the owners of IP rights' and that 'Australian business is shying away from using the IP system because of the costs of protection, the uncertainty and lack of support from the courts'.[25] There has also been debate about the performance of the courts in enforcing IP rights in the legal literature,[26] at gatherings of the IP community,[27] and in government reviews of the Australian IP enforcement system.[28] In 1999, the Working Group on Managing Intellectual Property, convened as part of the National Innovation Summit, concluded that while generally effective, the Australian IP system delivered less favourable protection for innovation than comparable systems overseas because, among other things, the system was less certain in relation to patent validity determinations by the courts.[29]

At around the same time, the Advisory Council on Industrial Property ('ACIP') wrote a report which posited that '[a] major problem facing Australian patent owners is the difficulty in effectively enforcing their rights against infringement' and that the major concern was 'substantial uncertainty regarding the outcomes of enforcement action.'[30]

Such concerns have been reinforced by the small amount of existing empirical analysis of patent litigation in Australia. One such article, by Duigan and Dowling, suggested that Australian patent owners won overall in only one instance (or 2 per cent) of 56 patent cases which they had examined in the period 30 April 1991 – 31 December 1997.[31]

However, their research was not intended as a rigorous, empirical study of patent enforcement: rather, the paragraph which reported these results was one small part of an extended article about High Court patent decisions and the tests for validity. The method by which they reached the 2 per cent figure is therefore unclear.[32]

Alerted by his scepticism of the results reported by Duigan and Dowling — since his Honour had in fact presided over one case where a patent owner was successful and suspected that there were others — Justice Drummond conducted his own, more extensive review of the Australian situation for patent enforcement. Justice Drummond examined a total of 59 judgments in the Federal, Supreme and High Courts, constituting all the infringement judgments reported in the Intellectual Property Reports over the period 1990–2000. He found that patent validity was upheld in 34 per cent of cases and patents were found to be valid and infringed in 20 per cent of cases. The difference between these studies suggests at the very least that there is further scope for analysing the outcomes of patent litigation in Australia.

We believe that there are two fundamental problems with the current debate. First, the failure to adopt a rigorous and scientific method of collecting, coding and analysing the data on judgments has led to markedly different estimates of patent owners' win-rates.[33]

This makes it difficult, if not impossible, to resolve the contentious issue about whether existing levels of protection for patent owners are too low. There is also a dearth of data following from the debate that occurred around 1999–2000. The second problem is that some commentators seem implicitly to assume that the optimal rate of enforcement in the courts is such that the patent owner should win every time. This contentious assumption needs to be examined. Both of these issues are addressed by the present study.

We have already argued that effective enforcement plays a crucial role in generating benefits from the patent system. As we have seen, this argument is easy to develop at a conceptual level, but what does 'effective enforcement' imply in practice? Does it, for example, mean that once a patent has been granted, the owner of the patent should be expected to win every case that goes to court? In 50 per cent of cases? Those who have criticised the patent determinations made by the courts have notably not sought to specify any particular optimal rate of enforcement. The attempt to specify any appropriate 'win rate' is complicated by at least two important factors: the intrinsic nature of IP rights and selection biases in dispute resolution processes.

In any given set of proceedings, the patent owner may have to prove two things: that the patent is valid; and that it is infringed. To put the matter diagrammatically, there are four possible outcomes in patent litigation, but only one (the shaded box below) is good for the patent owner.

Table 1: Possible Outcomes in Patent Litigation

|

|

|

VALIDITY

|

|

|

|

|

Invalid

|

Invalid

|

|

INFRINGEMENT

|

Infringed

|

Patent Valid

|

Patent Invalid

|

|

|

Patent Infringed

|

Patent Infringed[34]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not Infringed

|

Patent Valid

|

Patent Invalid

|

|

|

|

Patent Not Infringed

|

Patent Not Infringed

|

|

This is true of most property rights: in order to enforce your rights, you have to show both that you have rights and that they cover the alleged infringing acts. However, unlike physical property rights, IP rights are highly uncertain along both dimensions: so much so that they have been referred to as 'expensive lottery ticket[s]'.[35] Most importantly, some degree of uncertainty is inevitable due to the nature of these rights.

First, validity is uncertain. The grant of a patent by IP Australia does not provide a guarantee that it will be held valid if challenged in court.[36]

Economists therefore refer to patent rights as probabilistic: in other words, a granted patent represents only a probability that the owner has a right to exclude competitors.[37] The proportion of issued patents which are valid will depend on the standard of proof applied by the court and on factors such as the quality of the examination process (which may depend on many factors, including the experience of the patent examiners within the area of technology) and the complexity of the patent.[38]

Most importantly, some level of uncertainty here is inevitable, regardless of the resources available to examine patents. Even with a thorough examination of patent applications, some 'bad patents'[39] will be granted. There are a number of reasons why the validity of patents cannot be finally determined at the time of grant. First, some patents are filed in new areas of technology and the patentability and scope of patentability of those technologies may not be known until considered by a court. The infamous 'business method patents' are one recent example of an area of economic activity new to patenting. Second, it is impossible for patent examiners to determine ex ante whether a patent application fulfils all of the necessary criteria for patentability.[40] Some prior art may have been overlooked in the examination process, for example, which will only be uncovered after a party — the alleged infringer — with very focused incentives spends substantial resources to locate it. Thus we would expect that a proportion of patents will be found invalid if challenged in court.

The second dimension of uncertainty relates to a patent's scope. The scope of a patent is determined by the claims — the statements, drafted by the patent applicant, which state the boundaries of the legal monopoly claimed by the patent owner.[41] Unlike the boundaries of a piece of real property, which can at least be seen in the real world, the boundaries of a patent claim are written in words that attempt to predict or cover products not yet in existence or activities not yet occurring. It is hard to write a perfect application for a patent that details all of the characteristics which embody the invention. The full meaning and scope of these claims cannot be known in advance but will be determined by the court's eventual construction.[42] In many cases it is not self-evident whether the alleged infringement falls within the meaning of the words of the claims. As a result, it is impossible to articulate precisely the boundary of patent rights and therefore difficult to prove that someone else has infringed on a patent owners' property. Thus, there is a reasonable expectation that even in the cases where a patent is held to be valid, not all patent owners will win infringement cases and the result on infringement will not be completely predictable.

In summary, in thinking about patent enforcement, we need to remember that a patent is quite different from a property right in a tangible physical asset. A patent gives its owner the right to attempt to enforce the patent against a possible infringer, in circumstances where that infringer may, if the patented technology is valuable enough, spend vast sums of money attempting both to invalidate the patent and to limit its scope. Given these features of the real world, we should not expect patent owners to win 100 per cent of the time or even close to that number. Even acknowledging this much, however, does not tell us what an appropriate rate would be.

The other factor that we need to take into account in considering what is an appropriate 'win rate' is that only a small number of patent disputes are pursued all the way through to the issue of a judgment by the court and, significantly, those which are so pursued may not be representative of the population of patents, nor even of the population of patent disputes.

We can think of the patent system as a big funnel. Of all patents that are applied for, some (a significant proportion) are granted. Of the thousands of patents that are in force at any given time, only a small proportion will have infringement detected and in only some cases will such detection lead to a dispute. Even where there is a dispute, it may begin and end with the exchange of letters and/or negotiations, without infringement proceedings ever being filed in court.[43] Moreover, filing legal proceedings is itself a stage in negotiations. Many of the disputes that end up being filed in the courts are resolved in out-of-court settlements, leaving only a tiny fraction that end up being resolved by a judge.

Consider the figures from the US. Lanjouw and Schankerman,[44] in their study of patent enforcement, found that:

• the rate of filing of patent cases across technology types for the period 1978–1999 was 19 case filings per thousand patents, which varied significantly across technology fields and other factors like the size of the patent owner; and

• about 95 per cent of all patent suits filed are settled by the parties before the conclusion of trial,[45] 85 per cent of these settlements occurring very quickly, before even a pre-trial hearing is held.

More important for present purposes are the factors which determine whether a case will be litigated through to judgment and whether these factors are likely to influence or skew the outcomes. There is a vast theoretical literature, particularly in the field of economics, on this question. First, and most obviously, the stakes must be high. Patent litigation is expensive and is unlikely to be undertaken unless the expected payoff is greater than the cost of the suit, taking into account the risk of losing.[46] High stakes alone are not likely to skew outcomes, if they are symmetrical — that is, equally high — for both parties. Economic analysis of the dispute resolution process by Priest and Klein suggests that, if we assume that parties to a dispute:

• are rational;

• are not behaving strategically;

• have equal stakes; and

• have symmetrical (equal) information

then litigation will occur when both the plaintiff and defendant are optimistic about their chance of success, which makes it difficult to find a mutually agreeable settlement.[47] This is most likely to occur in cases which fall close to the decision standard — in other words, in the cases that are too close to call.[48] In cases where the legal rule clearly favours one side, rational parties will settle. Obviously, if both parties are optimistic about their chances, in any given case one side is wrong. But if we assume that errors are distributed normally — that plaintiffs are as likely as defendants to make errors about their chance of success and likely to make errors of the same magnitude — then we would expect win-rates to gravitate towards 50 per cent.

However, the assumptions that underlie the Priest and Klein model are not necessarily true in patent litigation. First, the model is based on 'single issue' litigation.[49] Patent litigation is generally more complex than that, as most cases involve the two issues outlined above: validity and infringement.

Second, the stakes are typically asymmetric. Often, the patentee will have a lot more at stake in the litigation than the alleged infringer. Most defences in patent litigation involve some challenge to the validity of the patent or some claims in the patent. A patentee which loses its patent, or its most valuable claims, loses not only against the defendant but will no longer be able to stop other competitors from copying its invention.[50] Theories of litigation suggest that if one party has higher stakes in the litigation, it will settle more cases where there is some doubt about the outcome,[51] and will spend more on litigation that is pursued through to trial, in order to increase its chances of winning.[52] On that basis, we might expect a win rate higher than the Priest and Klein 50 per cent expectation.[53] On the other side of the equation, a defendant may have less at stake. As Farrell and Merges have recently pointed out,[54] one key problem is that defendants cannot capture all the value of a successful challenge to validity: if a patent is revoked, or narrowed, all competitors in the field covered by the patent receive the benefit. This gives defendants strong incentives to settle.[55]

Other assumptions in the Priest and Klein model are also difficult to apply to patent litigation. For example, strategic behaviour by patentees cannot be ruled out. How all these factors will interact is difficult to predict. The strongest conclusion we can draw from this literature is that the question of what an 'appropriate' outcome is for patent owners is fraught with multiple difficulties. The economic theories outlined above suggest a range of possible pictures of how we might expect results to look for patent owners. It is not our purpose to construct a model of how patent litigation should come out, or provide the definitive answer on what the optimal 'win rate' is. Rather, we aim to highlight the complexities involved in drawing any such conclusion, as a caveat to the analysis we present below.

If theory gives us only limited insights into what the optimal 'win rate' might be, can we gain more information by comparing the Australian systems to systems overseas? In the last four years there has been an explosion of studies, which are beginning to provide insights into the operation of the patent enforcement system in the US. This explosion is due, in part, to the availability of large-scale databases of legal information in that country. According to these studies, the number of patent lawsuits settled in or disposed of by US federal district courts doubled between 1988 and 2001,[56] although it remained relatively constant as a proportion of patents granted.[57] We know that only approximately 1.5 per cent of patents are ever litigated: about 2000 patent cases are filed each year, involving 3000 patents.[58] We also know that post-filing settlement rates are high: according to Lanjouw and Schankerman, only 0.1 per cent are litigated through to trial.[59] In her detailed empirical study, Kimberley Moore found that 6.9 per cent of cases filed proceeded all the way to trial.[60] Settlements also usually occur early — soon after proceedings are filed.[61] Some of these studies have also considered outcomes in litigation. When it comes to outcomes, the results of these studies vary widely. Estimates of the rate at which patent validity is being upheld range between 54 per cent and 67 per cent.[62] Estimates of the rate at which infringement is found vary between 48 per cent and 58 per cent.[63]

The US studies have provided a highly contestable and complex picture of the operation of the US patent system. They are helpful in one key respect: in making it clear that patentees do not win in 100 per cent of cases, or even close to that figure, in an IP system which is arguably one of the strongest in the world. Care must be taken, however, in seeking to compare this system with the Australian system. Australian patent law and the patent system differ from the US in certain important respects. For example, Australian patent law does not have the procedure of 'continuations' which has been criticised as making it almost impossible for the USPTO finally to reject a patent:[64] Australian divisional applications have not been subject to the same criticisms. Our law and processes in patent litigation are also different. In US patent litigation, patents are valid unless 'clear and convincing evidence' is provided of invalidity,[65]

a standard which is higher than the current Australian standard, in which a challenger need only show that the patent is invalid on the balance of probabilities.[66] Nor does Australia have a doctrine like the US doctrine of 'wilful infringement', whereby an infringer can be required to pay triple damages if it can be demonstrated the infringer was aware of the violated patent before infringement occurred.[67] By raising the stakes faced by a losing defendant, such damages are likely to affect the cases which end up going to trial — providing defendants with a further incentive to settle. Furthermore, Australia does not use juries to determine questions in patent cases, which is an important fact given that the presence of a jury appears to be an influential factor in determining litigation outcomes in the US.[68]

Thus, while these studies are of interest, it is not valid to draw direct comparisons between the results obtained in US studies of patent litigation to any figures obtained in Australia. Unfortunately, there has been very little empirical study of outcomes in IP litigation elsewhere in the world.

In conclusion, neither theory nor studies in other countries is able to provide us with a clear picture of what the outcomes of patent litigation in Australia 'should be'. This does not mean that an empirical study is not useful. A rigorous study can give us a clear picture of just what is happening in Australian courts. This may, or may not, dispel some of the myths about patent litigation in Australia. If nothing else, we would expect that this information would be of interest to practitioners who are advising clients about their prospects in litigation. Finally, as we outline further in the conclusion, such a study can act as a springboard for further studies of how the patent system is working.

One of the reasons why few empirical studies have been done of patent enforcement in the courts is that no consolidated sources of data on cases and their outcomes exist. Like the US scholars who have undertaken recent studies, we have had to construct our own database of patent enforcement outcomes from a range of sources.

Our main source of data has been judgments issued by the courts. In order to quantify the rate of patent enforcement in Australian courts, we have attempted to code the entire population of patent litigation cases in Australian courts over the period 1997–2003. We used a number of publicly-available case law databases in order to capture all of the relevant decisions. IPRIA researchers read every decision and recorded data about those decisions in a custom-built database.[69] We then supplemented the resulting database with information from a variety of other sources, as noted below. One of the major contributions made in this study is the rigorous methodology applied to the collection and codification of the data on patent enforcement.

This study is restricted to the population of all[70] patent enforcement decisions[71] rendered by Australian courts of superior jurisdiction, both reported and unreported,[72] in relation to patents for the period 1 January 1997 – 31 December 2003.[73] By 'courts of superior jurisdiction', we mean decisions of the State Supreme Courts, the Federal Court of Australia and Full Federal Court, and the High Court of Australia.[74] 'Patent enforcement decisions' are defined as final[75] decisions rendered in court proceedings where a patent owner has sought to enforce its rights: that is, where a patent owner initiates court action, for example by filing an infringement action, and cases where the owner cross-claims for infringement in proceedings brought by another party.[76] The population does not include decisions on appeal from the Patent Commissioner, for example, appeals from refusals to grant a patent, or from oppositions.[77] We are concerned with the use of the courts by IP owners in enforcing their rights and the calculations facing IP owners in making the decision to sue for infringement, rather than questions concerning the quality of decision-making by IP Australia.[78] A list of the decisions which are included in the scope of this study is included in the Appendix to this paper.

One important point to note about this study is that it is confined to those cases which proceed all the way to judgment. We have not undertaken any analysis of the numbers, or types, of patent cases filed in Australia, or any analysis of how many of those cases settle. An ACIP report in 1999 provided some figures, noting that from 1993–96, between 20 and 39 patent cases were filed each year in the Federal Court of Australia.[79]

These figures would include not only infringement actions but also appeals from decisions of the Patent Commissioner, for example in opposition proceedings. Estimates from practitioners of the proportion of cases which settled ranged between 30 per cent and 95 per cent. Further research is clearly warranted on the rate of settlement and the factors which influence such settlement — but it is beyond the scope of this paper.

It is surprisingly difficult to find all the relevant decisions of the courts and to be confident that we have caught them all. We took a series of steps to ensure the comprehensiveness of the list. First, we searched three different electronic databases in order to generate a list of relevant decisions. We adopted this approach in preference to the other possible approach — looking only at cases reported in a set of law reports like the Intellectual Property Reports[80] — because the editors of law reports select their cases on the grounds of their importance as precedent. The importance of a decision as precedent is not relevant to our study. Our aim was to be as comprehensive as possible in capturing the decisions of the courts.[81]

We tested three different generally available databases:

• CaseBase, a proprietary case citator, which contains summary records of decisions issued by Australian courts compiled by employees of the publisher, LexisNexis Butterworths;

• AustLII,[82] a set of free online databases which contain full text decisions, both reported and unreported; and

The LexisNexis Butterworths Unreported Judgments Database, which, despite its name, contains full text judgments of both reported and unreported decisions of all the relevant courts.[83]

The courts provide the same decisions, in electronic format, to both AustLII and LexisNexis Butterworths.[84]

The list of decisions was generated by querying each database for all references to 'Patents Act'.[85] This search was chosen because it seemed to us that all decisions of interest (as defined above) would have to include a reference to the relevant legislation under which the claim for infringement was being brought.[86] After trials of the three databases, we found that we obtained the most comprehensive results using the full text LexisNexis Butterworths Unreported Judgments Database. For various reasons, the CaseBase searches and AustLII searches missed relevant decisions.[87] We are confident that, having taken these several steps and cross-checks, the list of decisions we have reviewed represents the real population, or at least the best approximation we are able to generate using publicly-available information.[88] In any event, of all the forms of IP studied, we believe that we are least likely to have missed patent decisions.[89]

Every decision identified using this search was then reviewed: first, to determine whether they were within the scope of our study or not (see the discussion of scope, above Part III(a)) and second, to record relevant data. Cases that were beyond the scope were discarded, leaving approximately one third of our initial list for closer review.[90]

The backbone of this study is a unique, custom-built database of information distilled from decisions issued by the courts in patent enforcement proceedings. Broadly speaking, we have collected three types of data about each decision: case data, patent data and outcomes data. This is the first Australian study to record information about patent proceedings in such detail.

The first stage in the construction of the database was a close reading of all decisions within the scope of the study. The reading and coding was undertaken by IPRIA researchers in close consultation with the authors,[91] and a range of data about those decisions was recorded in a custom-built relational database. A key determinant of the information we have collected was reliability. We only collected data which we could code consistently and in a replicable way. In order to ensure the reliability of the data, several procedures were adopted:

• the database, as well as the data collection methodology, was developed and refined using a small pilot population of cases;

• the variables were selected to reduce, so far as possible, the subjectivity of coding decisions: we have avoided collecting data on matters of impression;

• the database was also designed to maximise consistency across coded decisions and to minimise coding error, for example, by requiring the reader to choose from a list of static variables, rather than allowing subjective coding by comments fields;

• data which might be of interest but which cannot be reliably gleaned from decisions issued by the court was rejected;[92]

consistency was maximised by having a second researcher undertake a 'blind read' of difficult decisions;

in every situation where there was some doubt about the coding of a variable, there was consultation between the researchers and the supervising author;

comprehensive checking was done of decisions coded early in the process, to maximise consistency with later coding decisions.[93]

Even adopting this approach, however, it should be noted that it is difficult to reduce information gleaned from the decisions of judges into quantitative results. In some decisions, it was difficult to discern exactly what issues were being decided and on what basis. In other cases, determining how to categorise a decision required an exercise of judgment.[94] Further, there are many factors we do not record and cannot control for: inter alia, the quality of the patent, the financial resources of the parties, the skill of legal representatives and expert witnesses, strategic choices made by the parties in how they run their cases and what arguments they run, or appeal, and behaviour on the part of judges.[95] Collecting this type of data of course would be extremely difficult and, in some cases, impossible. Finally, there are some issues of considerable interest that we could not address at all. For example, we have not been able thus far to consider damages awards in patent cases because awards are very rarely included in the final merits judgment issued by the court.

Some basic information about patent proceedings is not available from reading decisions issued by the courts. We therefore supplemented the information in the decisions with data from court databases and IP Australia's patent database, as noted below.

In relation to every decision included in the database, we have recorded:

• case details: the name and citation details of the decision, the court where the case was heard and the court file number;

• case type: appellate or original;

• important dates: issue date of the proceedings;[96] hearing date; and decision date;

court time: the total number of hours of court time spent on the proceedings;[97]

the parties, judges and counsel involved in the case;[98] and

whether the decision is the 'ultimate' decision in the period studied:[99] in other words, whether the decision is the 'last word' of the courts on whether a given patent is valid and infringed, up to the end of 2003.[100]

Written decisions of the courts contain only limited information about the patent that is the subject of the decision. Using the patent number, we searched IP Australia's PatAdmin database[101] for additional information about the litigated patents, namely:

• the earliest priority date of the patent: this provides information about the stage during a patent term when litigation occurs;

• the technology classes into which the patent is classified; and

• the country of origin of the patent, as recorded in IP Australia's PatAdmin database.

Some of the most important information in the database relates to the findings of the court. We have recorded separately the results for each patent dealt with in the decision.[102] Broadly speaking, we have separately recorded the results on both the validity and infringement of each patent. We refer to the outcome on each of these dimensions of the decision as a determination. Thus, each decision may include two determinations: a validity determination and an infringement determination.[103]

For each determination, we have recorded two items: the outcome and the grounds for that outcome. In relation to outcomes, there are five possible results, which we have expressed from the perspective of the patent owner:

• All claims/allegations upheld: patent owner successful in all respects: either all of the patent claims in issue were upheld as valid, or all the allegations of infringement were successful;

• No claims/allegations upheld: patent owner failed in all respects: either none of the (litigated) patent claims was held valid, or no infringements were held to be proved;

• Some claims/allegations upheld: patent owner partially successful: in validity determinations, this means that not all of the claims in the patent in issue were upheld, resulting in a valid, but narrower patent. In infringement cases, it means that some, but not all allegations of infringement were successful;

• Not determined: the court did not make a finding on the relevant issue: because, for example, it was not raised, it was conceded, it was separately decided or it was not necessary to decide for the purposes of the judgment;[104] or

Remitted: this means that the proceedings were remitted to a lower court for final determination.

In relation to grounds, where the patent owner has either had some or none of its claims upheld, we have also recorded the grounds for the determination (for example, lack of inventive step or lack of novelty).[105]

In this section we report the results of our population of litigated patents in the period 1997–2003. The statistics are largely descriptive — they provide an insight into the population of judicial patent enforcement decisions during a recent period of time. However, it should be noted that these statistics do not predict anything about future patent litigation. More sophisticated techniques are unavailable to us given the relatively small number of cases we have in our dataset, although we hope that in the future, as the size of our dataset grows, we will be able to expand the analysis. This paper also represents only a first attempt at analysis of the database and there are variables on which we have collected information but have not yet attempted analysis.[106] We hope to expand on the basic analyses here reported in future studies.

The first aspect of patent litigation we examine is an overall description of the extent of patent litigation in Australia. We first examine how many proceedings there have been in the six-year period examined. More importantly, we have obtained figures on how long these proceedings have taken. This is important because the length of the proceedings has an important effect on the cost to the parties: the longer the proceedings, the more expensive they will be. In order to compare like with like, we have separated the original proceedings from the appeals.[107] For both, we present information on two variables:

• case length: the number of days elapsed between the date of issue of the proceedings and the last decision date;[108] and

court hours: the total number of hours spent in court in the proceedings (including all preliminary events and skirmishes, directions hearings and the final hearing).

Note that we have chosen to analyse 'court hours', rather than the number of hours or days in hearings alone, as the figure which more truly indicates the true cost of proceedings. Patent litigation often involves multiple skirmishes prior to trial: disputes over discovery, pleadings and expert evidence may all involve lengthy hearings. The longest cases in our database in terms of court hours are invariably cases which involve multiple applications and notices of motion.[109]

Basic descriptive statistics on each of these variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics on Patent Proceedings

|

Type of Proceeding

|

Variables

|

|

|

|

Case Length (Days)

|

Court Hours

|

|

ORIGINAL

|

|

|

|

No of observations

(proceedings)[110]

|

29

|

25

|

|

Mean

|

1000.48

|

54.27

|

|

Median

|

915

|

50.67

|

|

Standard deviation

|

586.23

|

41.93

|

|

APPEAL

|

|

|

|

No of observations (proceedings)

|

23

|

23

|

|

Mean

|

418.91

|

11.81

|

|

Median

|

364

|

11.17

|

|

Standard deviation

|

262.85

|

6.10

|

Two matters of interest arise from these figures. First, the length of time that patent proceedings take and second, the apparently high rate of appeal in patent cases. We consider these two issues in turn.

The number of hours spent in court in patent proceedings is an important issue for disputing parties. Since 'time is money', especially when talking about lawyers' time, the number of hours in court is a proxy for the cost of the proceedings. Table 2 indicates that original proceedings typically require many more court hours than appeals: the average number of court hours is 54.27 for original proceedings (that is, approximately 11 full days in court) and 11.81 for appeals. It should be noted that without comparing these court hours, for example, to the average court hours spent on other types of litigation, it is not possible to draw general conclusions from this information, such as how expensive or complex patent litigation is compared to other kinds of litigation.[111] It is, however, relevant information for patent practitioners and patentees contemplating litigation.

The difference between the time taken for trials and appeals will not surprise any lawyer. In original proceedings, a judge must often deal with a significant number of pre-trial events such as the preliminary hearings dealing with the collection of evidence, disputes over the pleadings, the instruction of experts and dealing with pre-trial motions. Furthermore, the trial judge must hear extensive evidence, including the cross-examination of witnesses in particular. Appeals in the Full Federal Court[112] from a decision of a single Federal Court judge or a State Supreme Court are not hearings de novo. The court on appeal will not have to hear cross-examination of witnesses or be taken through the evidence as if the case were a fresh trial on the record.[113] An appeal is more concerned with whether a trial judge applied the law correctly to the facts as found and while appellate judges are entitled to take a different view of the facts from the trial judge, they will only overturn the trial judge where the trial judge's findings can be characterised as erroneous.[114]

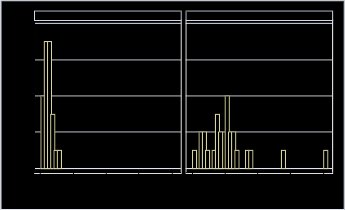

It is also interesting to note that the distribution of the court hours variable differs significantly by the type of proceeding. The distribution for original cases has a much larger standard deviation (41.93) than the distribution for appeal cases (6.10). This means that original proceedings vary significantly but that appeal proceedings are far more similar in terms of the time they take to resolve.[115] This is illustrated graphically by Figure 1.

Figure 1: Distribution of Number of Court Hours for Original (O) and Appeal (A) Cases

This observation is well in line with what we would expect, given that original proceedings must deal with a range of technologies which may vary from the relatively straightforward to the highly scientific and technical. In some areas, extensive time and expert evidence will be required to put the court in the position of the skilled addressee.[116] Furthermore, it is not only the length of the hearing which has the potential to vary significantly between different cases. Original proceedings also vary considerably in the forensic and strategic decisions taken: it is possible, for example, for a party to dispute many procedural points leading to more hearings and hence more hours spent in court, or more frequent appearances before the court in the lead-up to the hearing.

It is worth highlighting specifically the number of original proceedings we have at the lower end — cases where only a small amount of court time was required. We are sometimes inclined to forget that not all patent infringement cases are massive, multi-year undertakings and a closer look at the cases at the ends of the extreme of this distribution will illustrate the point. For example, the shortest set of original proceedings in terms of court hours — at just over four hours in total — was Datadot Technology Ltd v Alpha Microtech Pty Ltd.[117] The proceedings concerned an innovation patent covering a method of applying identity labels, called 'microdots', via a spraying mechanism to articles such as cars. In this case, not only was the technology relatively simple but, most unusually for patent litigation, the respondent did not appear. As a result, there was no need for cross-examination.

Another observation may be made about court hours. It has been noted by ACIP that it is disputes over validity which generally are the most complex and closely fought and hence which are the most drawn out and expensive in patent litigation.[118]

Our examination of the proceedings tends to confirm ACIP's view. The cases at the lower end of the scale are often cases where the technology is simple and validity is not in issue. If we look behind this histogram to the next two shortest original proceedings, we see that in both, validity was not considered by the court.[119]

Like any area of commercial litigation, patent litigation also has its extreme outliers: very long, complex cases. Looking behind Figure 1, it is clear that the longest cases are not just about complex technology, but rather, are cases where the legal issues are very complex and where forensic choices lead to additional court time. The longest original proceedings in the database remarkably concerns a petty patent, this time for water meter assemblies: Stack v Brisbane City Council.[120] This 'imbroglio of litigation', as Gummow J described it,[121] gave rise to at least 12 judgments on various issues and, most importantly from the perspective of the time taken in the proceedings, involved a hearing that continued for some 30 sitting days. In this case, it was the complexity in particular of the various proceedings on foot,[122] and the law relating to entitlement,[123] as well as forensic decisions, which appear to have caused the great length of the case. Similarly, in the second longest case by court hours, Old Digger Pty Ltd v Azuko Pty Ltd,[124] proceedings appear to have been complicated by the sheer number of grounds of invalidity pleaded, as well as an attempt to reopen a cross-claim after partial success on appeal.[125]

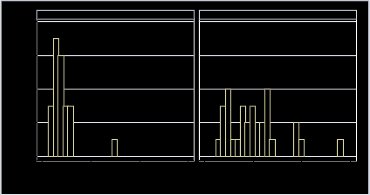

We observe very similar patterns when it comes to case length. Once again, original cases are much longer and more variable than appeals. The mean number of days elapsed from commencement of proceedings to decision for original cases is 1000 (2.7 years), while the corresponding figure for appeals is 418.91 (1.1 years). These distributions are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Distribution of Case Length (Days) for Original (O) and Appeal (A) Cases

In terms of case length, there is only one 'outlier' in the appeals: the case of Ramset Fasteners (Aust) Pty Ltd v Advanced Building Systems Pty Ltd. It was long (1504 days, or just over four years) because the Full Federal Court heard the matter twice: first[125] on appeal from the decision at first instance and second[126] after the matter was remitted by the High Court. The longest original proceedings were Leonardis v Theta Developments Pty Ltd[127] at 2822 days (7.7 years).[128]

The second interesting observation that arises out of the data in Table 2 is the high appeal rate. The data indicates that out of a total of 52 proceedings which have generated at least one decision in the period 1997–2003, there are 29 original proceedings and 23 appeal proceedings.[129] This is borne out if we look at what proportion of original proceedings which are subject to at least one appeal: 17 out of 29 (59 per cent) were appealed to the Full Federal Court. A further four of the Full Federal Court proceedings involved a High Court decision.[130]

There is reason to believe that this is a high appeal rate compared to the overall caseload of the Full Federal Court. In 2002–03, 3216 matters were filed in the Federal Court (excluding corporations law, bankruptcy and native title).[131] 375 appeals from State Supreme Courts or the Federal Court of Australia were filed in the same period.[132] This suggests that the proportion of decisions which are appealed across the spectrum of Federal Court matters is significantly lower than the rate we have observed in patent law.[133] Without more general data on the appeal rate of other types of litigation it is not possible to evaluate whether a high appeal rate is unique to patent cases.

This high appeal rate may suggest that sorting occurs prior to the decision of the court in the original proceedings. Proceedings where the stakes are not sufficiently high to pursue to an appeal and those where there is less uncertainty as to the outcome (and hence less likelihood of a lower decision being overturned) are presumably often settled prior to trial — or never filed. In those patent proceedings where parties are prepared to proceed all the way to trial, the case is sufficiently important, and/or uncertain, to take the matter through further avenues of appeal. This is consistent with our intuition, as we know that patent proceedings, even at the original level, are very expensive and risky because the patent owner risks losing its patent.[134] Given the high stakes and costs, we would expect that the matter will be pursued through to an original decision only where the case is very important to both parties and hence worth appealing.

The population of appeals is further dissected in Table 3 below. In this table, we report on which parties brought appeals[135] and the results they obtained on appeal. Note that by 'results on appeal' we refer only to whether the appeal was successful — regardless of what the grounds were for the appeal.[136] So, for example, a case in which the patent owner appeals to the High Court and succeeds in having the Full Court judgment overturned has 'succeeded' even if the result of the High Court judgment is that the matter is remitted for further consideration by the Full Federal Court. The figures therefore tell us little about the actual outcomes for patent owners and alleged infringers, which depend on the final determinations of the court on validity and infringement. These determinations are reported in more detail later in this paper.[137]

Table 3: Population of Appeals 1997–2003

|

Party bringing appeal

|

Result on appeal

|

Full Federal Court

|

High Court

|

Total

|

|

Patent owner

|

Total number

|

6

|

4

|

10

|

|

|

Patent owner

successful[138]

|

1

|

3

|

4

|

|

|

Patent owner unsuccessful

|

5

|

1

|

6

|

|

Alleged infringer

|

Total number

|

5

|

0

|

5

|

|

|

Alleged infringer successful

|

2

|

0

|

2

|

|

|

Alleged infringer unsuccessful

|

3

|

0

|

3

|

|

Patent owner and alleged infringer

|

Total number

|

8

|

0

|

8

|

|

Patent owner successful

|

2

|

0

|

2

|

|

|

|

Alleged infringer successful

|

5

|

0

|

5

|

|

|

Both parties successful

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

A number of observations arise from Table 3. First, in the Full Federal Court, the numbers are about evenly split in terms of who brings the appeal: that is, in the period 1997–2003, alleged infringers appealed from the decision at trial about as often as patent owners. Note also that there are a substantial number of cases where both parties appealed some aspect of the judgment. On the other hand, in the same period, only patent owners had appeals heard in the High Court of Australia.[139]

Further examination of Table 3 gives some indication as to why the figures fall this way. In the period studied, the patent owner failed in its Full Federal Court appeal more often than the alleged infringer did. Five of the six appeals by a patent owner to the Full Federal Court were unsuccessful, and where both parties appealed, the patent owner was successful or partly successful in three of the eight proceedings. Results for infringers on appeal were more evenly split (three failures as compared to two successes in infringer-only appeals). Patent owners enjoyed more success in their appeals before the High Court, succeeding in three of the four appeals. We have referred earlier in this paper to a perception among the profession that courts, in particular the Federal Court, are 'anti-patentee'.[140]

It may be that the low rate of success in Full Federal Court appeals is a source of such perceptions. It is natural that appeal judgments attract more attention particularly among the profession than decisions at first instance. We would argue, however, that the 'score card' in the terms presented in Table 3 is less important, for patentees' purposes, than whether patents are ultimately (ie, in the final decision rendered by the court in the proceedings) being held valid and/or infringed. These issues are considered further below, in Parts IV(c) and IV(d). In particular, in our analysis of validity and infringement we have been careful to record the ultimate decision of the court — whether trial court, intermediate appellate court or High Court. We would argue that the figures look less 'grim' for patentees than is sometimes assumed.

The next issue of interest relates to the characteristics of the litigated patents. It should be remembered here that in talking about 'litigated' patents, we are only talking about those patents which have been litigated through to judgment — itself a subset of all those patents in relation to which proceedings have been filed — and the following discussion needs to be read with that in mind. Since our dataset has both original decisions and appeals, there is not a one-to-one relationship between the number of patents and the number of proceedings. In the period studied, 39 patents were litigated through to a court decision,[141] of which two were litigated twice.[142] This is a small number and means that we can present only very general information about the litigated patents, namely, the country of origin, the type of patents (petty or standard) and the age and type of technology embodied in the patent. This information is presented in Table 4.

Table 4: Characteristics of Litigated Patents by Country of Origin

|

Country of Origin

|

Patent Type

|

Number

|

Average Age of Technology

(Years)[143]

|

|

Australia

|

Petty/innovation patent

|

5

|

4.64

|

|

|

Standard patent

|

20

|

9.68

|

|

United States

|

Petty/innovation patent

|

2

|

2.54

|

|

|

Standard patent

|

8

|

10.04

|

|

Others[144]

|

Petty/innovation patent

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

Standard patent

|

4

|

9.88

|

|

TOTAL

|

Petty/innovation patent

|

7

|

4.04

|

|

|

Standard patent

|

32

|

9.82

|

This data is interesting because we can treat 'country of origin' of the patent as a proxy for the country of origin of the technology to which the patent relates.[145] We can see that most of the patents litigated in Australian courts relate to patents for technologies having their origin in Australia (25 of 39, or 64 per cent): the rest came from the US (26 per cent) and from other countries such as the UK, New Zealand and France (10 per cent). Most of the litigated patents in the population (over 80 per cent) are standard patents, while a small proportion are petty (or innovation) patents.[146] The average age of technology variable is calculated by determining the numbers of days elapsed between the date of earliest priority for the patent application (which was obtained by matching the data from the legal proceedings with the data from IP Australia on the patent details) and the date of issue of court proceedings.

The finding that the technology covered by 64 per cent of the litigated patents was Australian in origin is very striking when compared to data relating to patents granted in Australia. In the same period (1997–2003) an average of only 7.85 per cent of patents granted had their country of origin in Australia.[147] Striking, but not startling. We would expect that Australian companies (which are more likely to be involved in litigation involving patents the country of origin of which is Australia[148]) would be far more likely to litigate in Australia than foreign or multi-national companies, who are more likely to litigate in their own home market or in their most important markets (for example, the US).[149]

Table 5 presents data on the type of technology embodied in the 33 litigated patents, which we determined using a UK system known as the OST Classification.[150]

Table 5: Litigated Patents by Technology Type

|

OST Classification

|

Number

|

Per cent

|

|

Electrical devices

|

1

|

3.03

|

|

Information technology

|

1

|

3.03

|

|

Analysis, measurement, control

|

1

|

3.03

|

|

Pharmaceuticals, cosmetics

|

3

|

9.09

|

|

Biotechnology

|

1

|

3.03

|

|

Basic chemical processing, petrol

|

5

|

15.15

|

|

Mechanical elements

|

8

|

24.24

|

|

Handling, printing

|

3

|

9.09

|

|

Agriculture/food machinery

|

3

|

9.09

|

|

Space technology, weapons

|

1

|

3.03

|

|

Consumer goods & equipment

|

1

|

3.03

|

|

Civil engineering, building, mining

|

5

|

15.15

|

|

TOTAL

|

33

|

100.00

|

It is difficult to draw any significant conclusions from this information, particularly in the absence of readily available information on the number of patent cases filed with respect to the various forms of technology. We can, however, state that these results are broadly consistent with the patents found to be litigated in the US in Allison and Lemley's 1998 study, where a large proportion of the patents litigated were classified as 'general' (a category which appears to include mechanical and engineering-related inventions) or chemical.[151]

When this information was presented to some practitioners at a seminar, some surprise was expressed that there were not more litigated patents relating to pharmaceuticals. This, however, highlights a feature of the information we are presenting: the only patents we have recorded here are those where there has been a judgment issued by the court in the period 1997–2003, relating to validity or infringement of the patent. In fact, at present there are several ongoing proceedings in the Federal Court which concern disputes over pharmaceutical patents, but none of these generated a validity or infringement decision in the period of the study.[152]

The data above gives us some information about patent litigation proceedings and the characteristics of litigated patents. While these issues are of interest to both practitioners and scholars alike, it is the outcomes of patent litigation that have been the subject of much of the debate. In order to analyse this, we change our unit of analysis in the following section. Rather than looking at information at the proceedings level, we look at determinations made by the court with regard to validity and infringement separately, as they relate to each patent considered by a court. In other words, where there were multiple patents in an individual proceeding, we have treated the determination on each patent separately.[153] Later, we return to the question of how often the patent owner was successful overall in showing that its patent was valid and infringed.

The data on the outcome of patent determinations is presented in Table 6. In total, there were 53 determinations on patent validity: 34 were original determinations and 19 were determinations made on appeal.[154] We have also tabulated data on ultimate determinations, of which there were 32 in our dataset.[155] From both a legal and economic perspective, ultimate determinations are the most important to consider: a patent owner who wins at trial and in the Full Federal Court but has lost in the High Court has still lost, even though a majority of the determinations were favourable.

Table 6: Patent Validity Determinations, 1997–2003

|

Determination

|

Original Determinations

(n = 34)

|

Appeal Determinations

(n = 19)

|

Ultimate Determinations

(n = 32)

|

|||

|

All litigated claims upheld

|

14

|

(41%)

|

5

|

(26%)

|

15

|

(47%)

|

|

Some litigated claims upheld

|

7

|

(21%)

|

3

|

(16%)

|

3

|

(9%)

|

|

No litigated claims upheld

|

13

|

(38%)

|

11

|

(58%)

|

14

|

(44%)

|

Looking first at the original determinations, the data shows that patent owners had all of their claims upheld in 14 (41 per cent) original determinations, some of their (litigated) claims upheld in 7 (21 per cent) and no litigated claims upheld in 13 (38 per cent). Note that the 'some litigated claims upheld' category is heterogeneous: it could include a case in which 1 of 30 claims was upheld and one in which 29 of 30 claims were upheld.[156]

The figure of 21 per cent of patents being held partially valid — ie, having some claims upheld — is quite a high proportion compared with similar studies in the United States. In their 1998 study, Allison and Lemley found that the US federal courts disaggregated claims in only 2.3 per cent of the patents litigated. This suggests that Australian courts appear to be using this method for narrowing patents more often than US courts.[157]

On appeal, the situation is slightly worse for patent owners: the percentage of cases where all litigated claims were upheld for patent owners fell to 26 per cent while the percentage of cases where the patents had no claims upheld increased to 58 per cent. But in considering these figures we must take into account the underlying population of appeal cases. The subset of patents where validity is in issue in the appeal may be a weaker set because it does not include those patents where findings of validity at trial were not challenged.[158] Actually, however, of the patents which generated a finding on validity on appeal, only 47 per cent (nine of the 19) were held invalid at trial, with a further four being held partially valid. A further six were held valid at trial. This is not an overwhelmingly weak set of patents. In fact, as illustrated in the next part, patent owners on the whole ended up slightly worse off after appeals (see below Part IV(c)(ii)).

But, as we noted earlier in this paper, it is easy to focus only on appeals, which tend to attract more attention from practitioners and lose sight of the cases that are not appealed. A better overall measure of findings on validity is to look at the ultimate determinations. Here, the outcome for patent owners looks much better: all of their claims are upheld in 15 of 32 determinations (47 per cent) of cases and partially upheld in a further three determinations (9 per cent). It is worth noting that these results are quite different from those found by Justice Drummond in his Honour's earlier study. Justice Drummond found that the patent was revoked in 38 out of 59 proceedings, or 64 per cent of the time.[159] However, using our data, patents have only been held invalid by the courts in 14 of 32 ultimate determinations, or 44 per cent of the time.[160]

International comparisons are of limited use, for the reasons we have already outlined above.[161] For what it is worth, however, our figures are in line with one of the US studies of outcomes on validity. Allison and Lemley, in their 1998 study, found that patents were held valid 54 per cent of the time and invalid 46 per cent of the time.[162] Other US studies have found higher rates of success for patent owners, with both Landes and Posner and Moore finding success rates of 67 per cent for the patent owner on validity.[163]

However, in the US patents have a presumption of validity in the courts which is absent in Australia.[164]

Another issue that patentees might be interested in is whether trial court determinations on validity are upheld on appeal. We do not have extensive figures on this issue as yet because we have a relatively small number of cases: 16 in total in our six-year period where we have both the original and the appeal decision on validity. What we do have, however, is shown in this matrix in Figure 3. The shaded squares are the situations where the appeal court upheld the trial court's findings on validity.

Figure 3: Validity Determinations: Original and Appeal[165]

|

|

ORIGINAL

|

|||

|

APPEAL

|

|

Win

|

Partial Win

|

Loss

|

|

Win

|

3

|

–

|

1

|

|

|

Partial Win

|

1

|

2

|

–

|

|

|

Loss

|

1

|

3

|

5

|

|

One feature of Figure 3 is particularly striking. In a majority of the cases (10 of the 16 cases), the appeal court upheld the finding of the trial court on validity.[166] In six cases, the finding of the trial court was overturned: however, note that in only one of those cases was the shift in favour of the patentee — (ie, from invalid to valid).[167] In the other five cases the patentee was worse off after the appeal court stepped in: either because:

• the patent went from valid to invalid (one case);[168]

• the patent went from partially valid to invalid (three cases);[169] or

• the patent went from valid to partially valid (one case).[170]

This is consistent with the information reported above in Table 3 in which it was noted that patentees, particularly in the Full Federal Court, had a lower rate of success in the period 1997–2003 than alleged infringers.[171]

It should be noted that there is ample opportunity for appeal courts to overturn findings of trial judges in relation to the validity of a patent, as most grounds of invalidity involve a combination of questions of fact and questions of law.[172] The issue of whether an invention lacks an inventive step, or is anticipated by a prior publication or act, are questions of fact. Appeal courts are reluctant to interfere with such findings, conscious of the significant advantage of a trial judge who has had the benefit of a longer, more detailed education in the relevant technology.[173] However, construction of the claims in a patent is a question of law,[174] and an appeal court which takes a different view on the proper construction of the claims may quite easily reach a different result from that reached by the trial judge.

Why do patentees lose on validity? We have tabulated the grounds used by the courts revoking some or all of the claims in the litigated patents in Table 7.[175] We have also reported the percentage of determinations in which specific grounds for invalidity were used by the court. For example, we have 20 determinations where a trial court revoked some or all of the patent claims. In three of those cases, manner of manufacture was reported as one of the grounds for invalidity. Therefore, manner of manufacture was a ground for invalidity in 15 per cent of the relevant original judgment determinations.[176] Similarly, 50 per cent of original judgments where the patent owner lost (or was partially unsuccessful) had obviousness as one of the grounds.

Table 7: Grounds for Patent Invalidity

|

Grounds for Invalidity

|

Original Determination

(n = 20[177]

|

Appeal Determination

(n =

14)[178]

|

Ultimate Determination

(n =

17)[179]

|

|||

|

Manner of manufacture

|

3

|

(15%)

|

0

|

(0%)

|

1

|

(6%)

|

|

Entitlement

|

1

|

(5%)

|

1

|

(7%)

|

1

|

(6%)

|

|

Novelty

|

8

|

(40%)

|

4

|

(29%)

|

8

|

(47%)

|

|

Obviousness

|

10

|

(50%)

|

4

|

(29%)

|

6

|

(35%)

|

|

Fair basis (s

40(3))[180]

|

9

|

(45%)

|

3

|

(21%)

|

5

|

(29%)

|

|

Description (s 40(2))

|

2

|

(10%)

|

2

|

(14%)

|

2

|

(12%)

|

|

Utility

|

1

|

(5%)

|

0

|

(0%)

|

0

|

(0%)

|

|

Clarity

|

3

|

(15%)

|

2

|

(14%)

|

5

|

(29%)

|

As we can see from Table 7, overall, the most common grounds for invalidity were novelty, obviousness and fair basis.[181]

Is this in line with what we would expect? We would expect, if the patent examination system is working properly, that the grounds of invalidity which succeed in court would be grounds where either:

• they are not examined by IP Australia, such as utility, secret use, or anticipation through prior acts;[182] or

they are more difficult to examine in the absence of expert evidence, such as lack of inventive step (obviousness).[183]

To the extent that other grounds come up, it may indicate that the law in relation to the ground is particularly uncertain, or that there is a difference between the approach at examination and the approach being applied by the courts.

Considering Table 7, the relatively high number of findings of 'obviousness' is not surprising but the prevalence of novelty and fair basis warrants further examination. First, consider novelty. An invention lacks novelty only if all the essential integers of the invention are found in a prior publication.[184] Prima facie, novelty ought to be accurately determined during examination. A patent examiner should, in theory, be able to locate and assess any prior publications in the form of documents. The exception would be where the invention has been anticipated by an act rather than a document.[185] One explanation might be that some of these novelty cases were in fact 'external' fair basing cases where loss of priority date under s 43 has led to anticipation by the patentee's own acts between the filing of the provisional specification and the complete specification — an area of law where the Federal Court has been criticised for being unduly harsh on patentees.[186] In fact, however, only one case within the period studied was of this kind.[187] Further examination of the cases shows that in only two cases was anticipation through acts an issue.[188] In the majority of the cases, anticipation occurred through a document (usually a patent), published prior to the priority date. This may be an issue warranting further, more detailed consideration.[189]

The number of cases where fair basing (meaning internal fair basing under s 40(3)) is a ground of invalidity also seems high, given that it is a ground examined by IP Australia.[190] The frequency with which this ground is raised may indicate a lack of certainty in the law in this area, which would certainly be consistent with criticisms found in the literature.[191]

On the other hand, it could indicate that while the law is relatively certain, its application involves difficult judgments on which courts may differ (and, being questions of construction, and thus questions of law,[192] issues where an appeal court will feel more justified in taking a different view). It will be interesting to see whether, in the future, the High Court decision in Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd leads to any reduction in reliance on this ground of invalidity.[193]

The data on patent infringement determinations is presented in Table 8. In total, there were 48 determinations on patent infringement: 31 were original determinations and 17 were appeals.[194] We have also tabulated data on ultimate determinations, of which there were 29 that related to infringement in our dataset.

Table 8: Patent Infringement Determinations, 1997–2003

|

Determination

|

Original Determinations

(n = 31)

|

Appeal Determinations

(n = 17)

|

Ultimate Determinations

(n = 29)

|

|||

|

All allegations upheld

|

15

|

(48%)

|

10

|

(59%)

|

16

|

(55%)

|

|

Some allegations upheld

|

0

|

(0%)

|

1

|

(6%)

|

1

|

(4%)[195]

|

|

No allegations upheld

|

16

|

(52%)

|

6

|

(35%)

|

12

|

(41)%

|